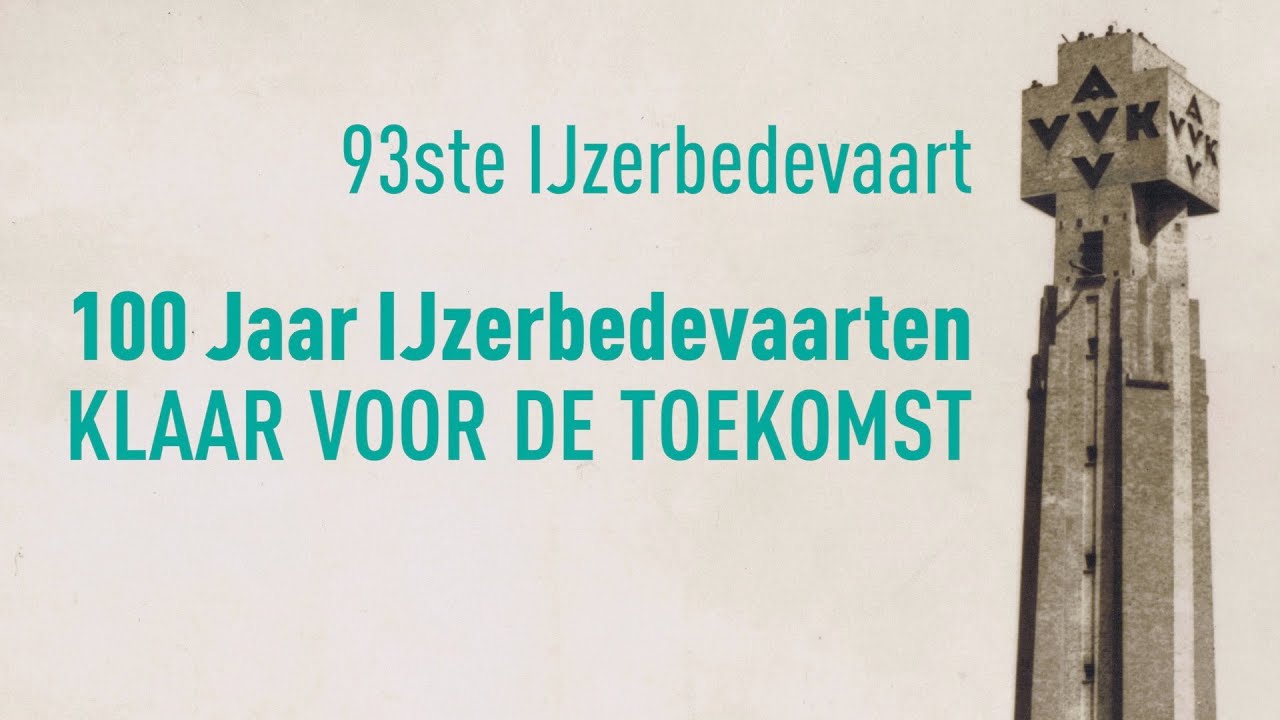

The first Yser Tower was inaugurated on 24 August 1930 | Diksmuide, Museum aan de IJzer

The Yser Tower

The Legacy of the First World War

In 1928 a fifty-metre-high tower rose in Diksmuide on the left bank of the Yser, a monument to pro-Flemish soldiers who died in the First World War. The Yser Tower became one of the most controversial monuments in Flanders.

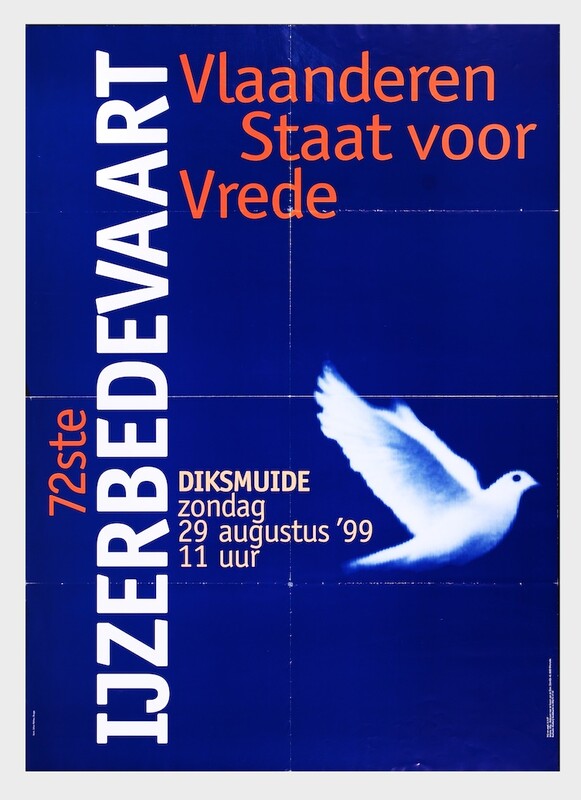

The Tower was built on the initiative of the Yser Pilgrimage Committee, a Catholic pro-Flemish group which since 1920 organised a commemoration for the soldiers who had died on the former Yser front. The tower also symbolised the striving for Flemish autonomy. The inauguration of 1930 gave rise to anti-Belgian protests. The Yser pilgrimages evolved from a ceremony of commemoration into a – sometimes turbulent – Flemish-nationalist demonstration.

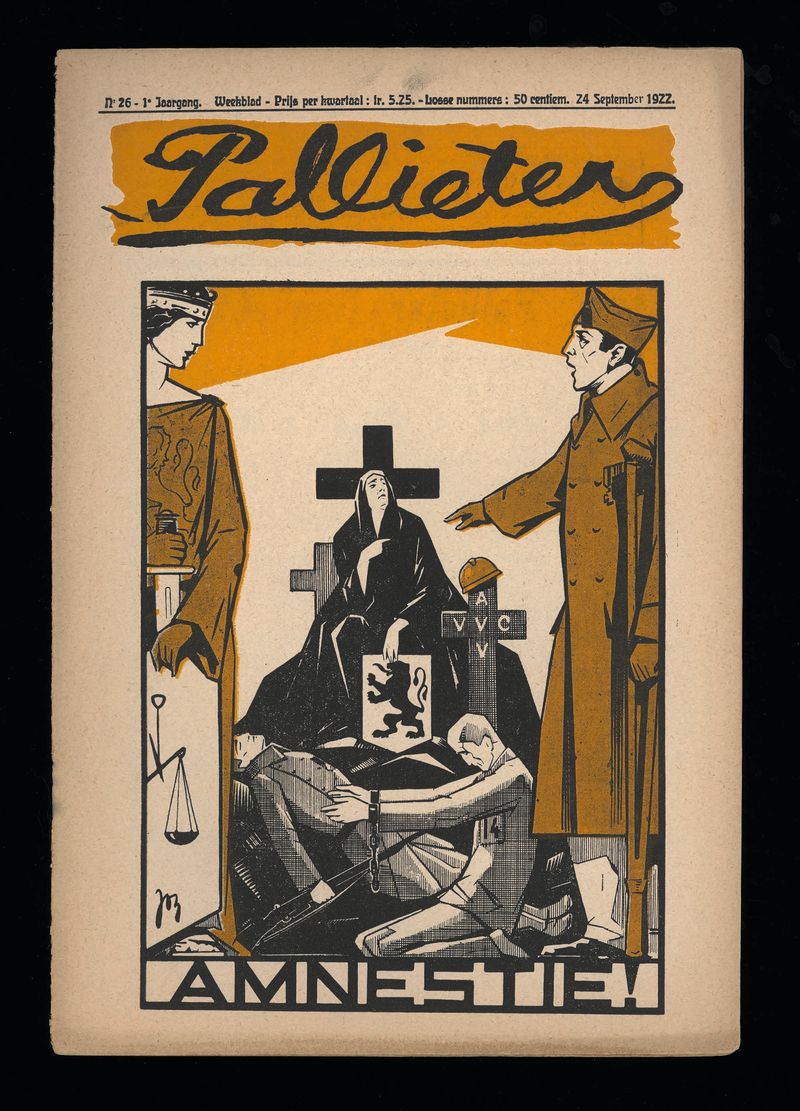

As a result of the collaboration of the Flemish nationalists with the German occupying forces during the Second World War the tower was blown up by opponents after the liberation. After its destruction the Yser Tower was rebuilt – higher than before – with donations from pro-Flemish Catholics and with money from the Belgian government. The abbreviation AVV-VVK (‘All for Flanders, Flanders for Christ’) was fixed to it again, as was the quadrilingual message of peace ‘No more war.’

Antwerp, ADVN | Archief voor nationale bewegingen

On a pump stone in the destroyed front-line village of Merkem pro-Flemish soldiers wrote in red paint: ‘Here is our blood, when will our rights come.’ In this way they were pointing out their disadvantaged position in the army.

The Legacy of the First World War

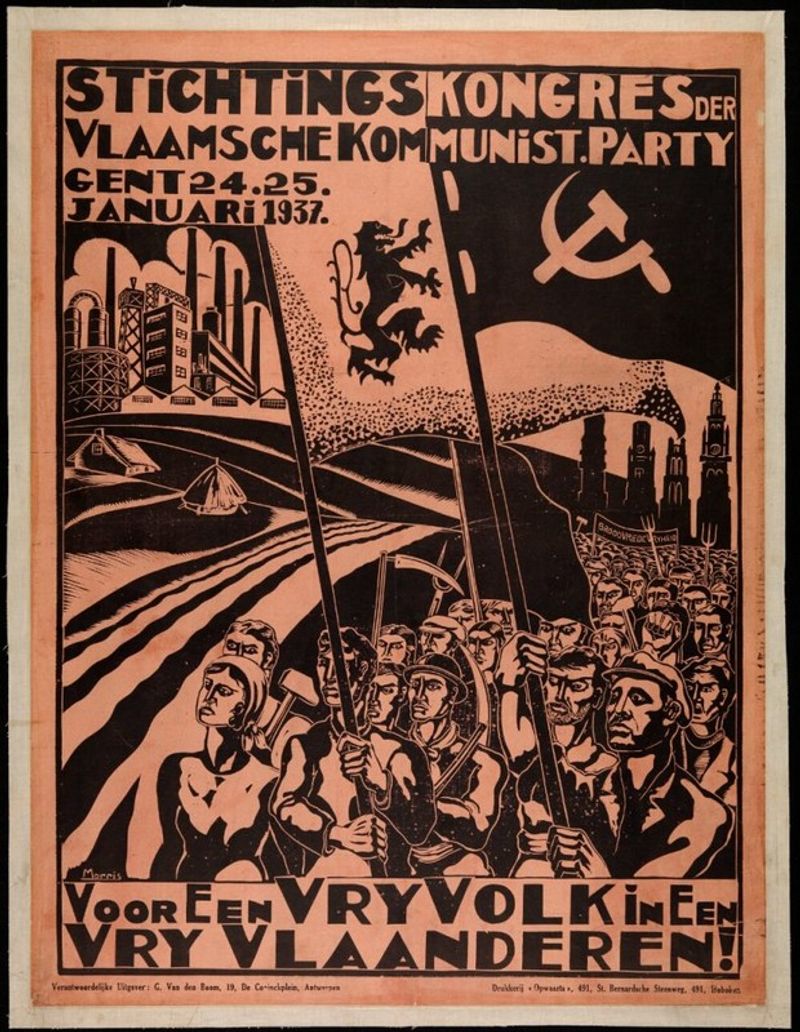

The First World War had a great impact on the language struggle in Belgium. The German occupiers exploited the Flemish question in order to weaken Belgium. The Flemish movement became radicalised, but also divided.

In the occupied area the Germans used the so-called ‘activists’ by suggesting there would be accession to Flemish demands, even a form of independence, in the future. That was unacceptable to most pro-Flemish supporters: they felt that Flemish demands should wait until after the war and they condemned activism as treason.

There were tensions on the Yser front too. In 1914 French was the official language of the Belgian army. Some Flemish soldiers took offence: they were risking their lives for a fatherland that paid scarcely any attention to their own language. The Front movement, a group of young Catholic intellectuals, undertook all kinds of protest campaigns to highlight the problem. The movement demanded Flemish army units and self-government for Flanders.

Political Flemish nationalism emerged from the discontent of the activists and of the Front movement. In the Front party members of the Front movement and former activists joined forces. There, but also in wider pro-Flemish milieus, the Yser Pilgrimage could count on great interest. With its symbolism –‘All for Flanders’ – the Yser Pilgrimage contributed to the growth of an independent Flemish identity, separate from Belgium.

Focal points

Discover more on this topic

Non-fiction

De IJzertoren, onze trots en schande

Van Halewyck, 1997.

Van IJzerfront tot zelfbestuur

Klaproos, 1993.

De Trust der Vaderlandsliefde: over literatuur en Vlaamse Beweging 1890-1940

Antwerpen, AMVC, 2005.

100 jaar IJzerbedevaarten in affiches 1920-2000

Peristyle, 2021.

De Groote Oorlog. Het koninkrijk België tijdens de Eerste Wereldoorlog

Houtekiet/Atlas Contact, 2013.

Greep naar de macht. Vlaams-nationalisme en Nieuwe Orde. Het VNV 1933-1945

Lannoo, 1994.

De schaduw van het interbellum. België van euforie tot crisis 1918-1939

Lannoo, 2017.

Repressie met maat? De omvang en de chronologie van de strafrechtelijke repressie van het Vlaamse burgeractivisme na de Eerste Wereldoorlog

In: Nefors, P. en Tallier P.A., En toen zwegen de kanonnen, Brussel 2010, p. 305-361

De overlevenden: de Belgische oud-strijders tijdens het interbellum

Polis, 2018.

Onsterfelijk in uw steen: soldatengraven, heldenhulde en de Groote Oorlog

Vrijdag, 2016.

Onvoltooid Vlaanderen. Van taalstrijd tot natievorming

Vrijdag, 2017.

De Frontbeweging. De Vlaamse strijd aan de IJzer

Klaproos, 2000.

Frans Van Cauwelaert. Politieke biografie

Doorbraak, 2017.

Onverfranst, onverduitst? Flamenpolitik, activisme, frontbeweging

Pelckmans, 2014.

Fiction

Mijn kleine oorlog

1947.

Het huis te Borgen

1950.

Het pakt der triumviren

1951.

Het verdriet van België

1983.

De varkensput

1985.

Alleen de doden ontkomen

1947.

De vermaledijde vaders

1985.

Zwart en Wit

1948.