‘The despair of Meensel-Kiezegem’ in Neuengamme near Hamburg. Sculpture by May Claerhout | SHGL, Zoia Kashafutdinova

The Drama of Meensel-Kiezegem

The Second World War

On 11 August 1944, two months after the Allied landings in Normandy, German soldiers and Flemish collaborators surrounded the Flemish-Brabant village of Meensel-Kiezegem. They searched the houses and herded the male occupants together. 71 residents were deported to the German concentration camp of Neuengamme. Only eight returned alive.

The raid happened after three members of the resistance had shot dead a collaborator from the village on 30 July 1944. His mother swore to avenge her son’s death. Through her contacts with the German occupying forces she was able to mobilise almost four hundred men to ‘teach the village’ – where she herself lived – ‘a lesson’. The results were disastrous.

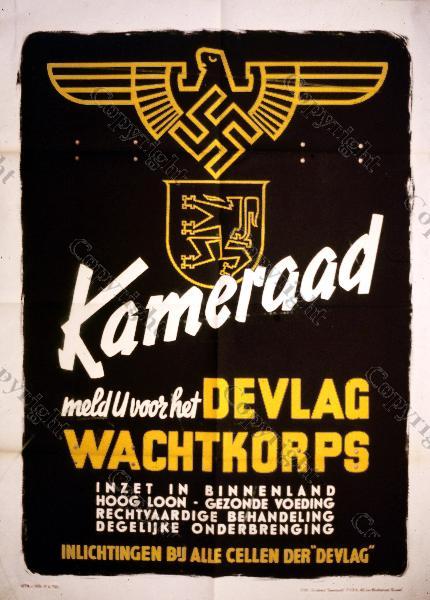

Not only in Meensel-Kiezegem, but all over the country the German occupation left deep wounds. The Second World War was not only a military but also an ideological conflict. The rift between resistance and collaboration would make itself felt for decades afterwards.

Antwerp, FelixArchief, Frans Claes

After the liberation in September 1944 the Germans continued to bombard Antwerp and surroundings until March 1945 with long-distance rockets, the so-called V-bombs (Vergeltungswaffen or retaliation weapons). Approximately 6,000 Belgians lost their lives as a result of these flying bombs. This is the Tuinbouwstraat in Antwerp, after the bomb struck on 26 October 1944.

The Second World War

On 10 May 1940 Nazi Germany invaded Belgium. That fitted in with Adolf Hitler’s plans to make Western Europe a single great Germanic empire. The government fled to France and from there to London. After eighteen days King Leopold III and the Belgian army surrendered. The Germans installed a military occupation administration, but kept on the secretaries-general, the governors and mayors to govern the country. With new appointments the occupier generally opted for pro-German candidates.

The occupation was a period of repression, fear and privation for the population. Food and fuel were scarce, citizens saw their freedom of movement restricted, press censorship was introduced and parliament was suspended. For some groups the consequences were even more extreme. From the autumn of 1940 the occupier announced anti-Jewish measures. From 1942 on the Germans picked up Jews during raids. Via the Dossin barracks in Mechelen they were deported to extermination camps. In October 1942 the occupier introduced compulsory labour in Germany. Men and women had to go there and work to keep the war economy operating. Most people simply tried to survive the war, but some sympathised openly with the occupier and others resisted clandestinely.

In September 1944 the Allies liberated most of Belgium. Still, the war was not yet over. In December there was a German offensive in the Ardennes and between September 1944 and March 1945 the German army bombarded Antwerp and Liège with V-rockets. Only on 8 May 1945 did Germany admit defeat.

Focal points

Discover more on this topic

Non-fiction

Kinderen van de repressie. Hoe Vlaanderen worstelt met de bestraffing van de collaboratie

Polis, 2017

Was opa een nazi? Speuren naar het oorlogsverleden

Lannoo, 2017.

De laatste getuige: hoe ik Breendonk en Buchenwald overleefde

Horizon, 2019.

Oorlog. Bezetting. Bevrijding, België 1940-1945

Lannoo, 2019.

Greep naar de macht, Vlaams-nationalisme en Nieuwe Orde. Het VNV 1933-1945

Lannoo, 1994.

Onverwerkt verleden. Collaboratie en repressie in België 1942-1952

Kritak, 1991

Burgers boven elke verdenking? Vervolging van de ecomische collaboratie in België na de Tweede Wereldoorlog

VUBPress, 1996

Was opa een held? Speuren naar mannen en vrouwen in het verzet tijdens WOII

Lannoo, 2020.

Van Genk tot Mauthausen: opmerkelijk verzet en collaboratie in Vlaanderen

EPO, 2009.

Voor Vlaanderen, Volk en Führer, de motivatie en het wereldbeeld van Vlaamse collaborateurs, 1940-1945

Manteau, 2012/2022.

Drang naar het Oosten: Vlaamse soldaten en kolonisten aan het oostfront

Polis, 2019.

Bastogne: de grootste slag om de Ardennen

Manteau, 2014.

Een klein dorp, een zware tol: het drama van collaboratie en verzet in Meensel-Kiezegem

Manteau, 2004.

De papegaai is niet dood: geheim agenten Albert Deweer, Albert Mélot en Albert Wouters – Gent 1944

Sterck & De Vreese, 2019.

Leopold III. De Koning, het Land, de Oorlog

Lannoo, 1994

Oorlogsburgemeesters 40/44. Lokaal bestuur en collaboratie in België

Lannoo, 2005

De Führerstaat. Overheid en collaboratie in België 1940-1944

Lannoo, 2006

Fiction

Allemaal willen we de hemel

Querido, 2014. (14+)

Het Verdriet van België

De Bezige Bij, 1983.

Valavond

Querido, 2014. (15+)

De Opgang

De Bezige Bij, 2020.

De draaischijf

Prometheus, 2022

De onbevlekte

De Bezige Bij, 2020.

Wil

De Bezige Bij, 2016.

Het complot van Laken

Horizon, 2019.

De hond van Roosevelt

Averbode, 2007. (14+)

Het land dat nooit was: een tegenfeitelijke geschiedenis van België

De Bezige Bij, 2015.

Zij zijn God niet

Abimo, 2015. (12+)

De Kavijaks

(2006)