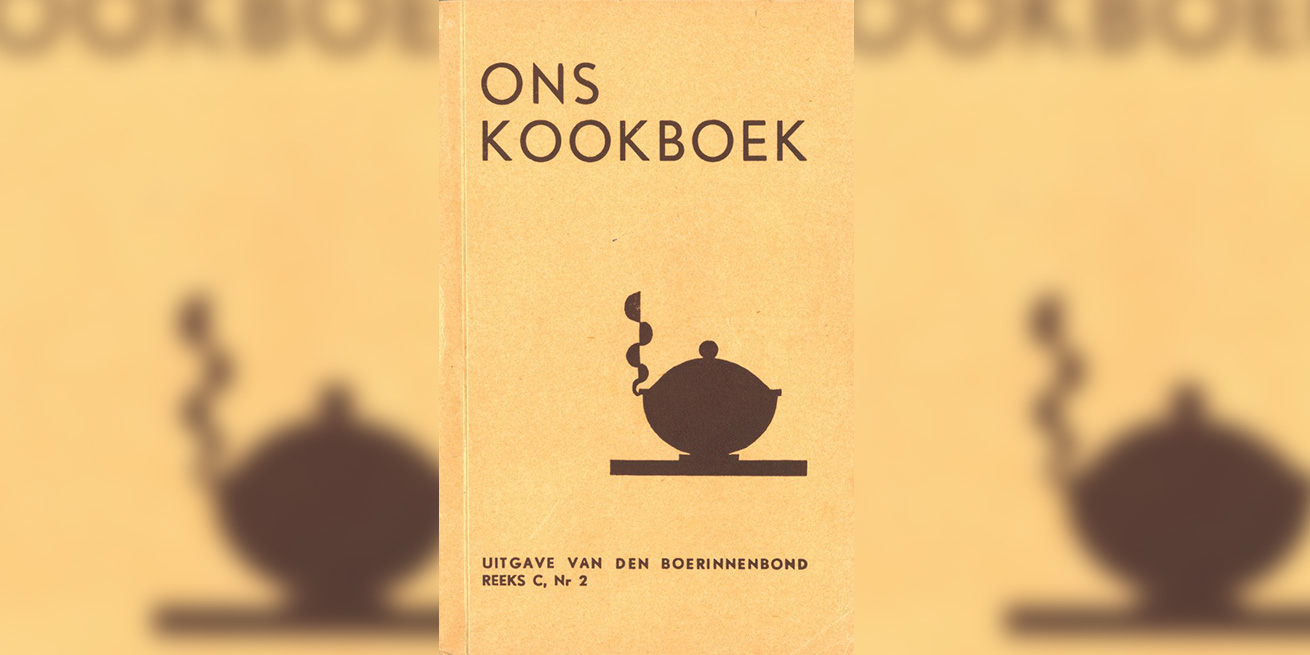

Our (Little) Cookbook appeared from 1927 onwards and was republished numerous times. It was intended as a manual to accompany the cooking lessons of the Catholic Farmers’ Wives Federation. Edition from 1949 | Dilsen-Stokkem, Dienst Cultuur

Our Cookbook

Culinary Canons

In 1927 there appeared on the initiative of the Farmers’ Wives’ Federation the first edition of Ons Kookboek (Our Cookbook). This kitchen guide grew into one of the most successful recipe books and set the standard in many Flemish kitchens.

The Catholic Farmers’ Wives’ Federation was aiming at the wives of Flemish farmers. Ons kookboek was designed to teach these women ‘to use everything they have on the farm as well and as usefully as possible, with variations’. It contained simple recipes for soups, sauces and desserts, as well as tips for keeping vegetable and fruit longer. The emphasis was on the importance of a balanced meal for the whole family. Balance meant then a combination of meat, potatoes and vegetables.

By now over 2,5 million copies of Ons Kookboek have been sold. It had an influence that cannot be underestimated on Flemish culinary culture. The slim book from 1927 grew thicker and thicker and evolved along with new kitchen trends. At present couscous, quinoa and hummus stand fraternally alongside classics like meatballs in tomato sauce and asparagus à la flamande.

Leuven, KADOC-KU Leuven. Fotocollectie KVLV/FERM. KFA23195

These women from the farmers’ wives’ guild of Herent, a hamlet of Neerpelt (today: Pelt), are learning how to preserve fruit and vegetables. The ‘bottling lessons’ were particularly popular between the wars.

Culinary Canons

The kitchen is a symphony of local and global influences. The Romans brought pepper, bread and wine. From the 16th century new foods came from America, such as turkey, potatoes and maize. Often these landed first on the plates of the rich and then very gradually penetrated to the poorer population.

In the 19th century clear national and regional ‘cuisines’ emerged. Before then recipes were mainly passed on by word of mouth, from generation to generation. But now popular chef-cooks wrote cookbooks which still determine the image of ‘classic’ French or Italian cuisine. In an age of rising nationalism they gave culinary form to their own nation.

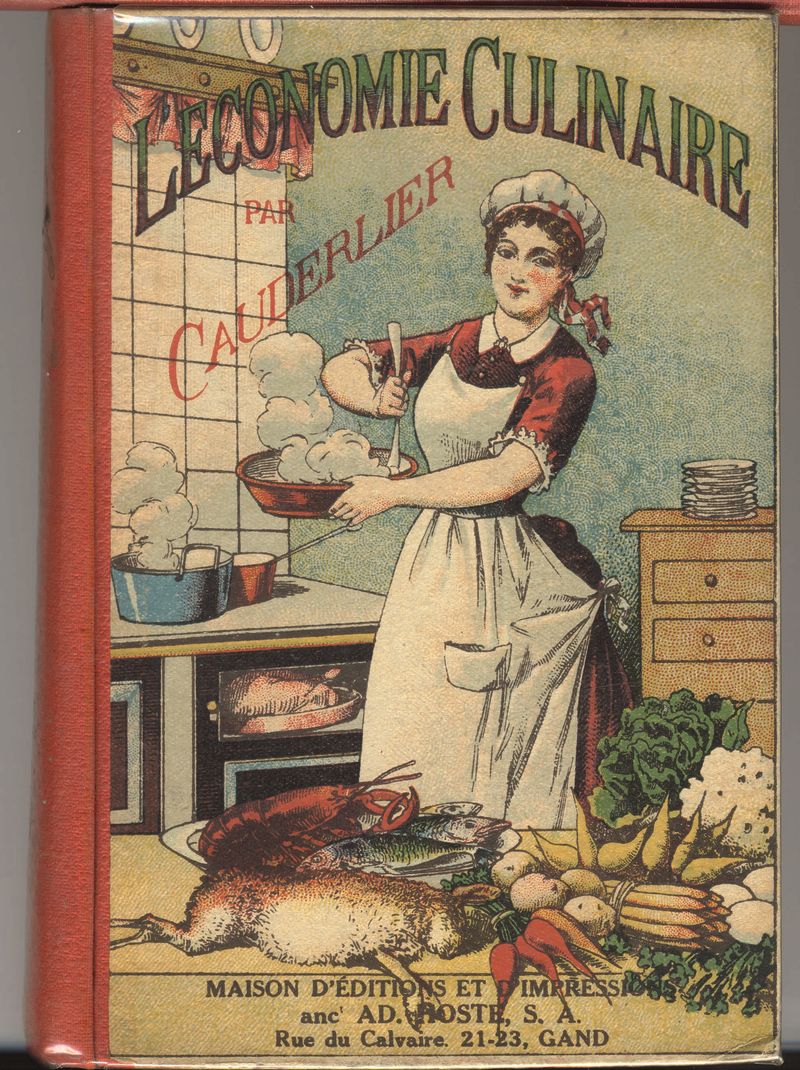

In 1861 Het spaarzame keukenboek (The Thrifty Kitchen Book) by the Ghent cook Philippe Edouard Cauderlier appeared. This book, originally written in French, brought mainly a budget-friendly version of recipes of great French chefs, although the target audience was still the haute bourgeoisie. At the same time it contained original ideas for ‘veal meat balls’ and ‘potatoes fried in fat’ – perhaps a recipe for chips.

Many cookbooks reflect a bourgeois eating culture: three meals a day, three courses and three elements (meat, potatoes, vegetables). For the common people that was unattainable. Meat, for example, was far too expensive to be consumed every day. Later Ons Kookboek promoted that eating pattern to broader sections of the population.

Focal points

Discover more on this topic

Non-fiction

Kebab met mayonaise: een hedendaagse kijk op traditionele en industriële eetcultuur

Stichting Industrieel en Wetenschappelijk Erfgoed, 2007.

Koffiestories: een complete koffiegeschiedenis

Hannibal Books, 2020.

Van mammoet tot Big Mac. Een geschiedenis van onze voeding

EPO, 2017.

Antwerpen à la carte. Eten en de stad, van de middeleeuwen tot vandaag

BAI, 2016.

Europa aan tafel. Een cultuurgeschiedenis van eten en drinken

Mercatorfonds, 2002.

België kookt! De eeuw van Cauderlier 1830-1930

CAG, 2004.

Goesting in Vlaanderen. Wat wij al eeuwenlang lekker vinden

Davidsfonds, 2009.

Arm en rijk aan tafel. Tweehonderd jaar eetcultuur in België

EPO, 1995.

Brood. Een geschiedenis van bakkers en hun brood

Vrijdag, 2021.

Leven van het land. Boeren in België, 1750-2000.

Davidsfonds, 2004.

Geschiedenis van de dorst. Twintig eeuwen drinken in de Lage Landen

Davidsfonds, 2007.

Fiction

Eten op zijn Vlaams

De Arbeiderspers, 2015.

De keuken van ons moeder: het culinair erfgoed van België

Homarus Culinaire Uitgeverij, 2007.