The Roman town wall of Tongeren, the only stone monument preserved above ground in Flanders from the Roman period | Brussels, Vlaams Agentschap Onroerend Erfgoed

Tongeren, a Roman Town

Romanisation of the Low Countries

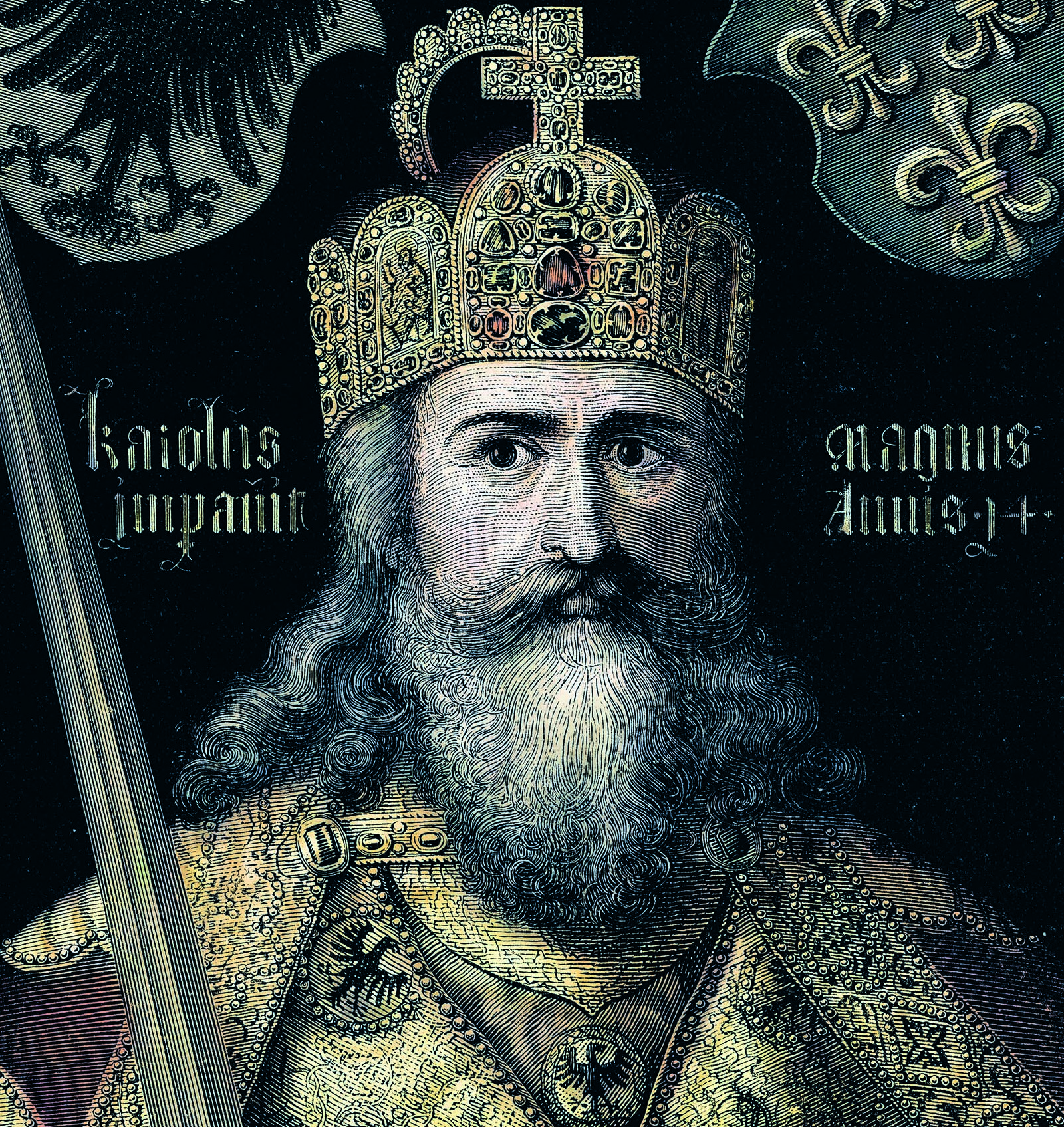

Tongeren, the first town in the territory of present-day Flanders, had several kilometres of town walls, an aqueduct and stone buildings in a style that blended local and Mediterranean influences. From a Roman army base Tongeren grew into a town with a Gallo-Roman culture.

Around the year 10 BC Roman administrators decided to build a town on a plateau near the Jeker, a tributary of the Meuse, on the site of a military camp. The surveyors designed a plan with a typically Mediterranean chequer-board pattern of streets. At first there still appeared houses of wood and loam in the traditional Gallic style. From the middle of the first century AD, there were more and more stone dwellings inspired by Roman models and often with under-floor heating and wall-paintings.

Tongeren grew into the principal town in the region and an important political, religious and military centre. The main town wall, at approximately 4.5 kilometres, was the longest rampart in the north of the Roman Empire. From the late 3rd century on a decline set in, although Tongeren remained important, partly as a bishopric from which a still young Christianity spread.

Tongeren, Visit Tongeren

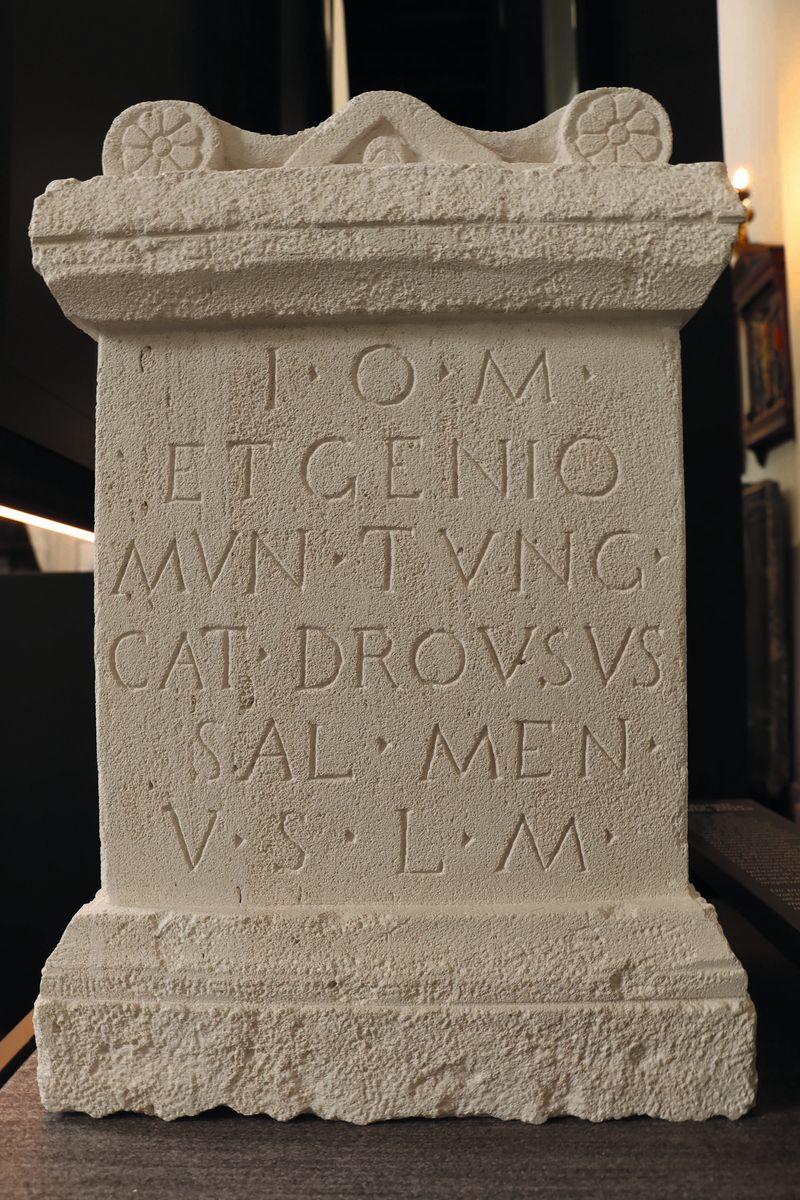

The Menapian salt trader Catius Drousus had an altar erected in Tongeren in honour of the Roman supreme deity Jupiter and the protective spirits of the town. The inscription calls Tongeren municipium Tungrorum, making it the oldest mention of a town (municipium) in what was later to become Flanders. Replica of the original.

Romanisation of the Low Countries

When Roman legions advanced to the Rhine and the North Sea coasts, they found in those areas a culture with Celtic and Germanic elements. After the first violent encounter a period of Romanisation began: in the space of four centuries the local civilisations changed their aspect radically through interaction with Roman culture.

It was the Roman commander Julius Caesar who conquered the area in about 55 BC, but only some thirty years later, under Emperor Augustus, did the military, cultural and economic impact of the Romans become visible. In the wake of the soldiers came traders. Besides goods these Southern newcomers also brought their ideas and customs with them. In some places those exotic habits caught on and, for example, Roman script and coinage were adopted. In some areas the local and Mediterranean cultures merged into a new whole. A good example of that cultural mixture was religion: Roman gods were identified with their local counterpart, like the Roman war god Mars with his Celtic counterpart Camulos. In architecture too cultural interaction was noticeable. For the first time in the Low Countries stone dwellings, bathhouses and under-floor heating appeared. Yet the process of Romanisation was far from straightforward. Depending on the place, the landscape and the cultural background of the local population, in many areas the indigenous elements remained dominant, or Roman elements were placed in a different, local cultural context.

Focal points

Discover more on this topic

Non-fiction

Romeinse sporen. Het relaas van Romeinen in de Benelux met 309 vindplaatsen om te bezoeken

Athenaeum-Polak & Van Gennep, 2014

De rand van het Rijk: de Romeinen en de Lage Landen

Athenaeum-Polak & Van Gennep, 2010

De Romeinse heerbaan: de oudste weg door de Lage Landen

Sterck & De Vreese, 2021

Op zoek naar Romeinse wegen in Nederland en België

Uitgeverij Verloren, 2022

Wee de overwonnenen: Romeinen, Kelten en Germanen in de Lage Landen

Uitgeverij Omniboek, 2020

Fiction

Een legioen in de val

Averbode, 1989. (12+)

De ring van Commodus

Clavis, 2014. (12+)