View of the Kemmelberg. During the Iron Age, but also during the First World War and the Cold War this hill had great strategic importance | Heuvelland, Toerisme Heuvelland, Thierry Caignie

Celts on the Kemmelberg

Celtic Centralisation of Power

Some 2,500 years ago, from their fortified hilltop headquarters on the Kemmelberg, Celtic nobles dominated the surrounding region both literally and figuratively. As the highest point in the area the hill, in what is now West-Flanders, had an excellent overview and became an ideal springboard for building an extensive trade network.

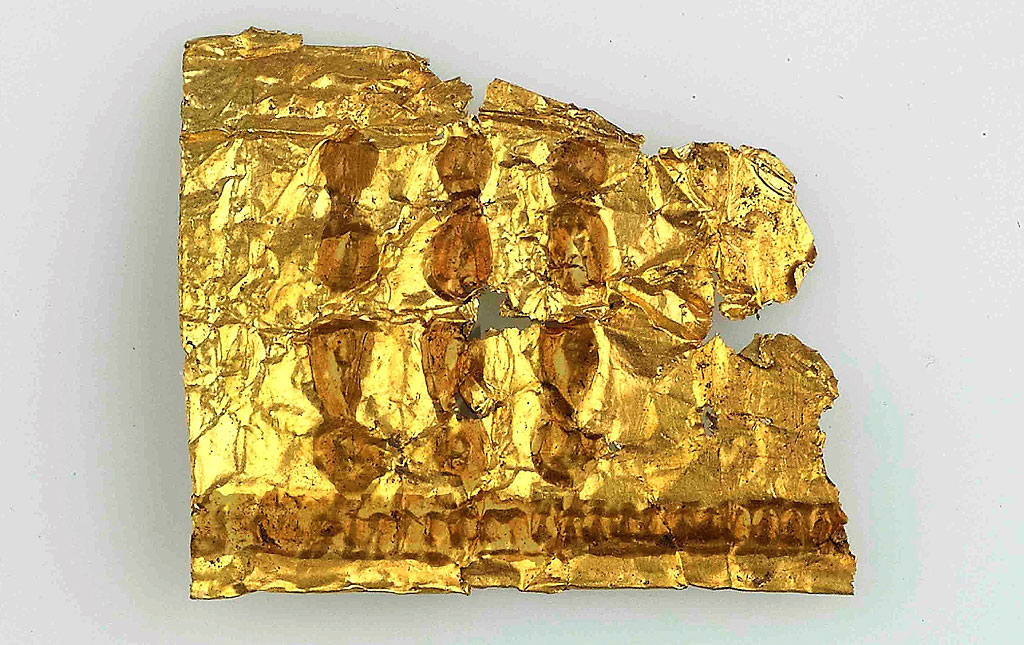

A formidable defensive system with moats, earth ramparts and wooden posts made the spot an impressive hill fort. Thanks to the steep slopes the wooden houses on the top were easy to defend. From on top of the hill the local elite controlled the trade routes. They may have derived their wealth from the trade in salt and iron ore. At the time salt was a luxury item that was brought inland from the North Sea. Local potters made red-painted earthenware with a unique style and decoration. We find their wares up to a hundred kilometres away. The importation and imitation of objects from the Mediterranean area show that the settlement formed part of an extensive network of trade contacts.

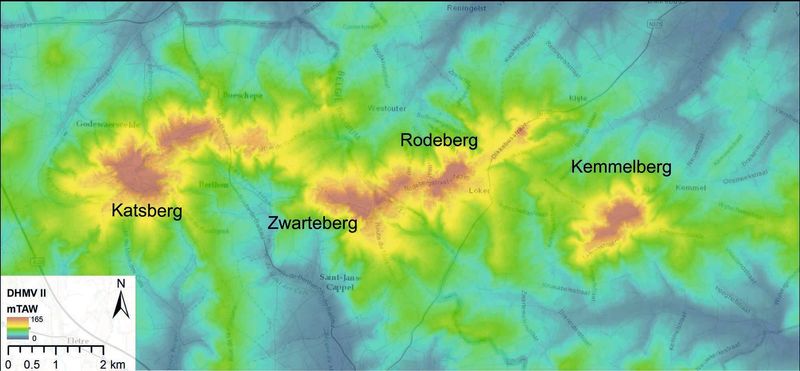

Geopunt

Like the Katsberg, Zwarteberg and Rodeberg the 156-metre-high Kemmelberg is an erosional outlier, also known as a witness hill. Erosional outliers were created 8 million years ago when the North Sea came inland and deposited sand banks. Because of their composition the sand banks were left behind when the sea retreated and the rest of the landscape eroded.

Celtic Centralisation of Power

The Romans depicted the Celts as war-mongering barbarians. The Celts themselves left no written sources, so that image persisted into the early 20th century. We now know, thanks to archaeological research, that Celtic society was organised in a more complex way than Roman writers maintained. For a long time, it was assumed that the first towns in North-West Europe originated in the first century BC through contact with Roman culture. But in the first millennium BC the Celts built settlements with urban pretensions, which controlled the surrounding area as power centres.

About 2,500 years ago, from the Celts’ original base in the valley of the Danube, their culture spread across large parts of Europe. That was the result of increasing contact between the regions, so that cultural interaction took place faster and on a larger scale. Typical of Celtic culture were the fortified settlements in high locations like the Kemmelberg. There the Celts built defensive bulwarks, protected by walls of woven branches, clay or loam, stone and wood. Some settlements, like the Heuneberg in Germany or that on the Mont Lassois in France, had up to five thousand inhabitants and an extensive street plan with districts, squares and sometimes monumental houses. The settlement on the Kemmelberg was less large. In a wide area around their settlements the Celtic inhabitants planted fields and meadows. They controlled the principal trade routes and so acquired wealth and power.

Focal points

Discover more on this topic

Non-fiction

Gisteren voorbij: een archeologische kijk op de geschiedenis van de oudste tijden

Garant, 1991

1000 jaar Kelten

Davidsfonds, 2009

Kelten en de Lage Landen: vechten om het beste deel

Davidsfonds, 2005

De oudste ronde van Vlaanderen. Een archeologisch parcours

Davidsfonds Uitgeverij, 2011

De Kelten: de geschiedenis van een Europees volk

Pearson Longman, 2005

De Oude Belgen: geschiedenis, leefgewoontes, mythe en werkelijkheid van de Keltische stammen

The House of Books, 2011

Zout. Een wereldgeschiedenis

Ambo, 2011

Wee de overwonnenen: Romeinen, Kelten en Germanen in de Lage Landen

Uitgeverij Omniboek, 2020

Op zoek naar de Kelten: nieuwe archeologische ontdekkingen tussen Noordzee en Rijn

Matrijs, 2006

Fiction

De koningsproef

Lannoo, 2002. (12+)

Het zonnewiel

Lannoo, 2004. (12+)