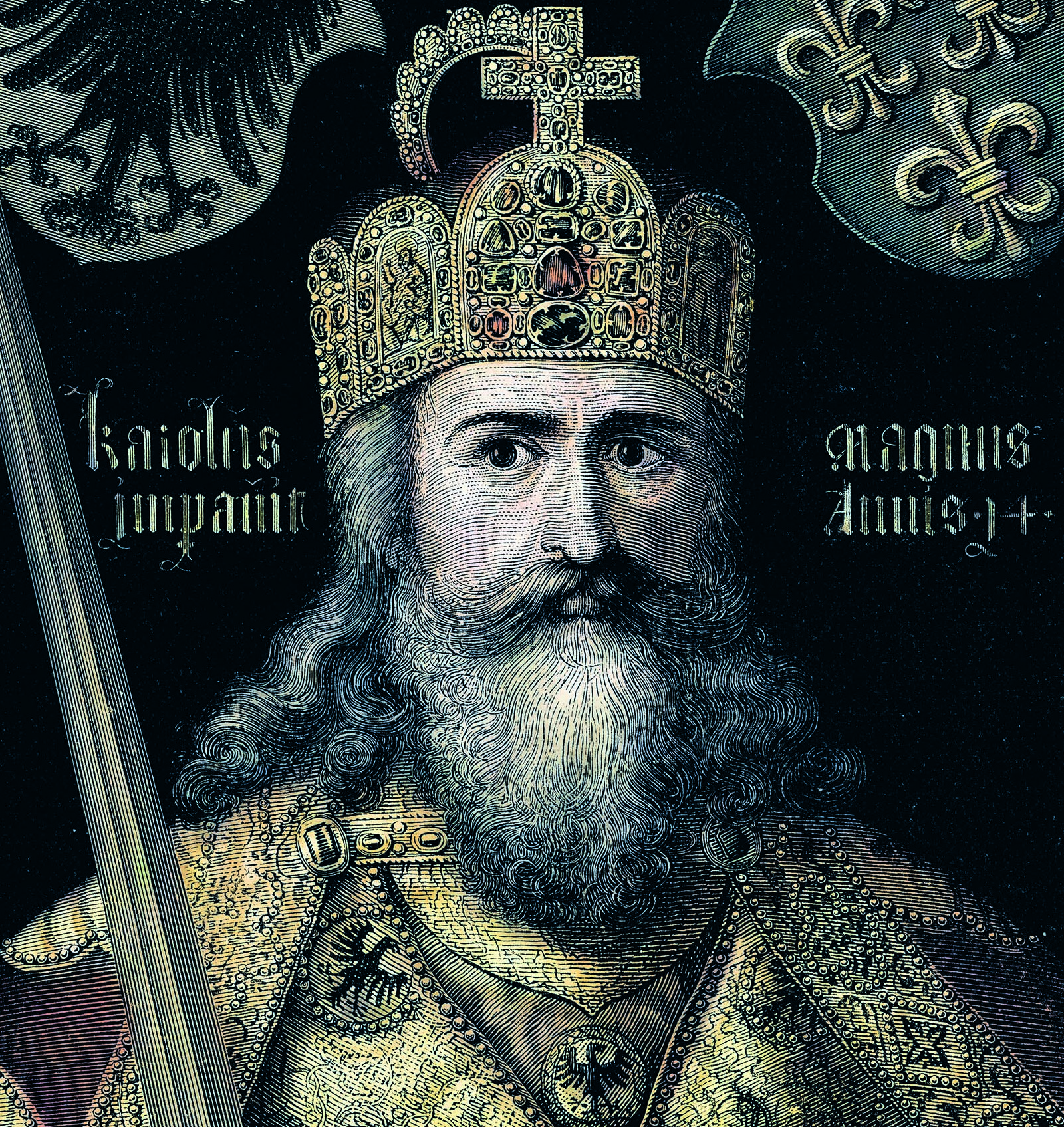

Albrecht Dürer, Charlemagne, 1513 | Neurenberg, Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Wikimedia Commons

Charlemagne

The Franks

In Rome, on Christmas Day in the year 800, Pope Leo III crowned the Frankish king Charlemagne Emperor. For Charlemagne the ceremony in the old St Peter’s Basilica had great symbolic value, since the king saw himself as the heir of the West-Roman emperors.

In 771 Charlemagne, a nobleman from a family with roots in the valley of the Meuse, became the sole ruler of the Frankish kingdom. By making war he expanded his kingdom until it covered a large part of Western and Central Europe. He tried to organise that extensive area as well as possible. It was divided to districts headed by a district count, and royal inspectors paid frequent visits to check on the counts. Charlemagne stimulated the development of art and science. He had schools set up, invited scholars to court and promoted intellectual life in abbeys. His period of rule was referred to much later as the Carolingian renaissancerebirth of Classical antiquity, originally used only for the 15th and 16th centuries. .

Paris, Musée du Louvre

This image of Charlemagne on horseback was inspired by the equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius on the Capitol in Rome. It makes it clear that the Frankish monarch placed himself in the line of the Roman emperors.

The Franks

As early as the 3rd century, Germanic tribes moved across the border of the Rhine into the Roman Empire. Usually as unwelcome guests, but sometimes the Romans deliberately gave the newcomers a fixed abode in the Empire and made them military allies. The Empire also often organised campaigns across the Rhine during the 4th century, in order to deport such groups by force to the Roman part of the world and present-day France with the intention of putting them to work as farmers or soldiers.

Among them were the Franks, an alliance of culturally closely related Germanic tribes such as the Salians and the Chattuars. From the 5th century on they gained more influence in the North-Western part of the Empire and took over power from the Romans. Meanwhile the Franks and the local Gallo-Roman population merged. In about 460 they moved further south, where they gradually extended their power over present-day France.

Strong Frankish kings such as Clovis and Dagobert I expanded their power, but around 700 the leaders of that Merovingiannamed after king Merovech, the supposed founder. dynasty became weak. The real power fell into the hands of their major domos, officials who controlled their possessions. Ultimately the major domos took power formally. They formed the dynasty of the Carolingians, with Charlemagne as its most important representative.

Focal points

Discover more on this topic

Non-fiction

Karel de Grote

Sterck & De Vreese, 2019.

Karel de Grote. een keizer op de grens tussen twee werelden

Davidsfonds, 2013.

Eeuwen des onderscheids: een geschiedenis van middeleeuws Europa

Prometheus, 2020.

De graven van Vlaanderen (861-1384)

Davidsfonds, 2020.

Gods filosofen: hoe in de middeleeuwen de basis werd gelegd voor de moderne wetenschap

Nieuw Amsterdam, 2014.

De volksverhuizingen: de geschiedenis van West-Europa, 375-800

Omniboek, 2020.

Vrouwen van Vlaanderen: een ongewone kijk op de geschiedenis van het graafschap Vlaanderen

Stichting Kunstboek, 2009.

De wereld in de tijd van Karel de Grote

Corona, 1999. (13+)

Vlaanderen in de middeleeuwen

Horizon, 2017.

De Franken en het christendom (550-850), een rechte lijn

Davidsfonds, 2016.

De Franken

Omniboek, 2021.

De middeleeuwers: mannen en vrouwen uit de Lage Landen, 450-900

Omniboek, 2020.

Karel de Grote

Aspekt, 2009.

Fiction

Karel de Grote

Daedalus, 2017. (strip)

Een olifant voor Karel de Grote

Uitgeverij Luitingh-Sijthoff, 2019.

De keerzijde van de keizer

Lannoo, 2012. (13+)

Karel ende Elegast

Amsterdam University Press, 2010.

De droom van Pepijn

Zwijsen, 2021. (9+)

Jonkvrouw

Davidsfonds, 2019. (15+)

Suske en Wiske. De pottenproever (nr. 209)

Standaard Uitgeverij, 1994.