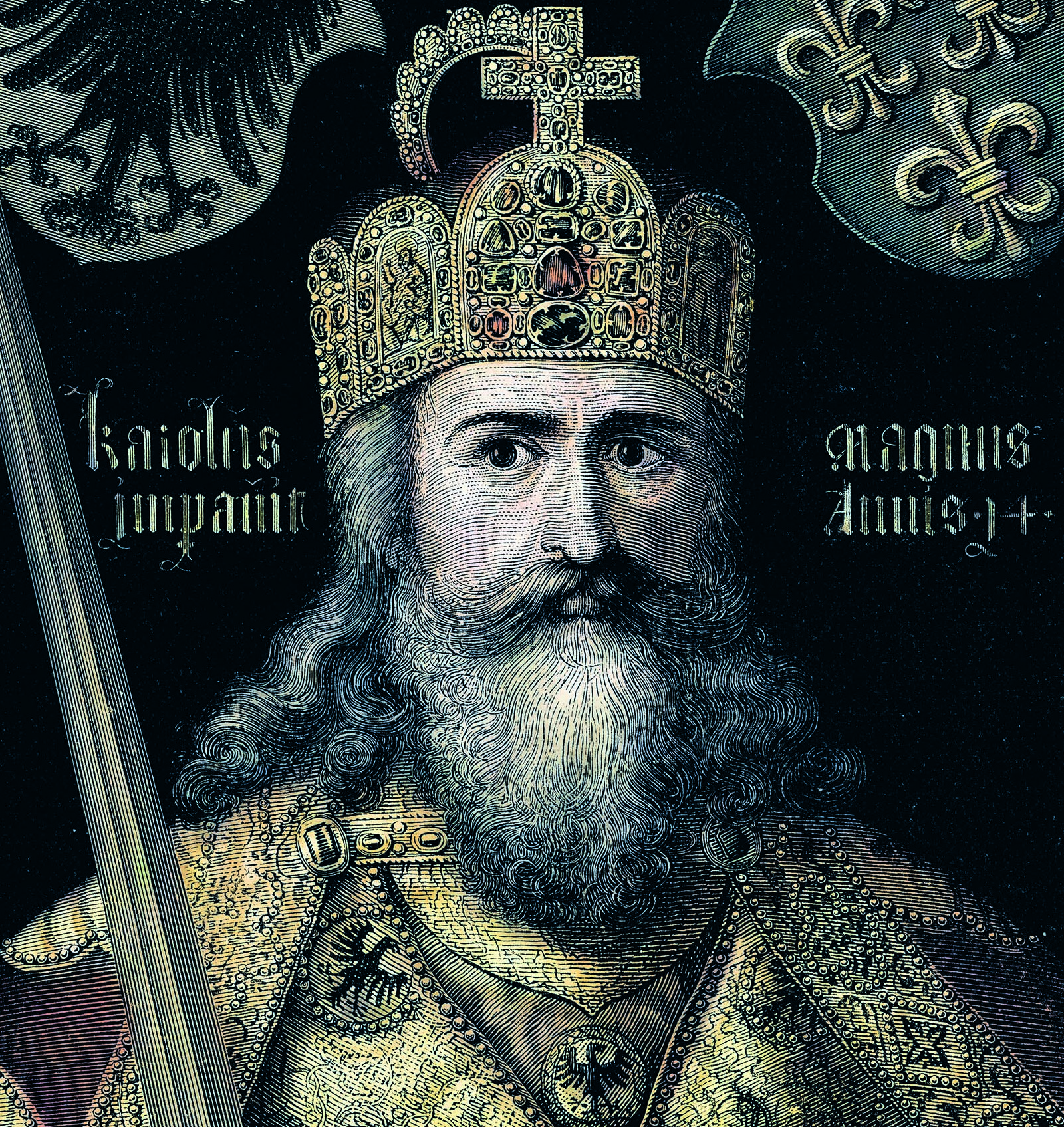

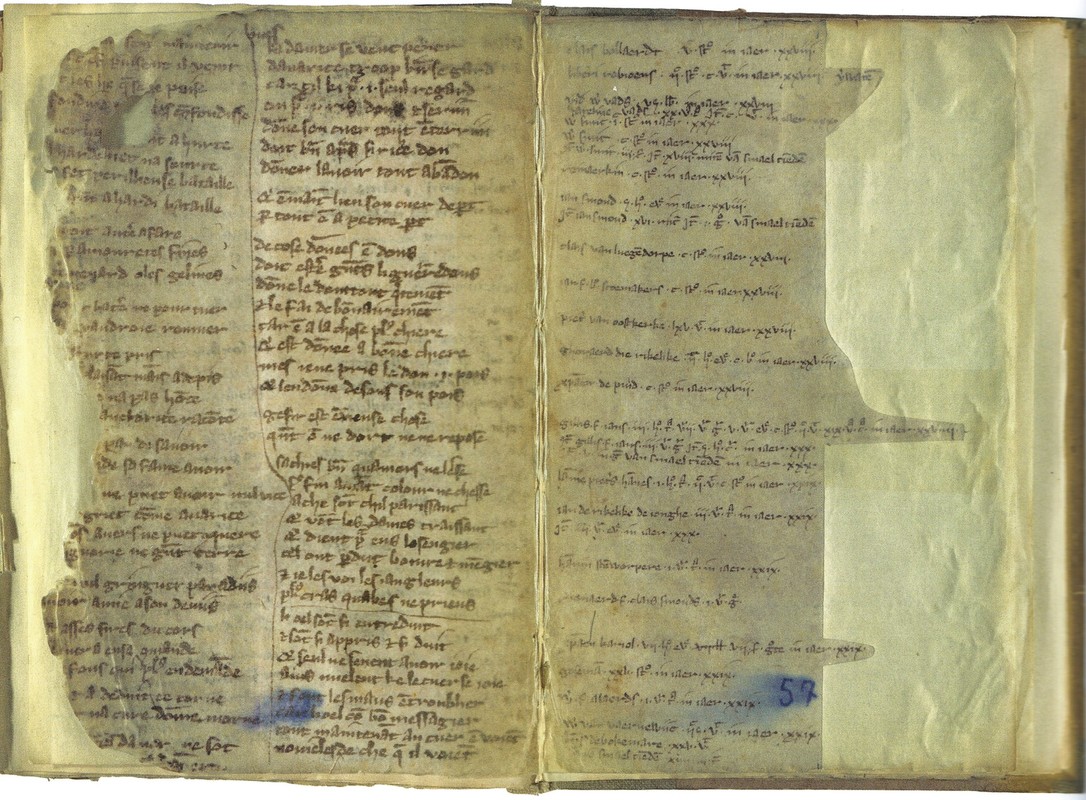

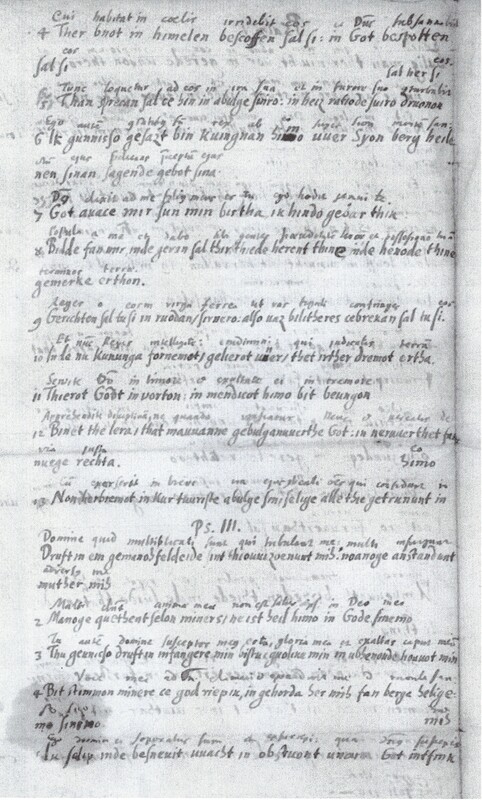

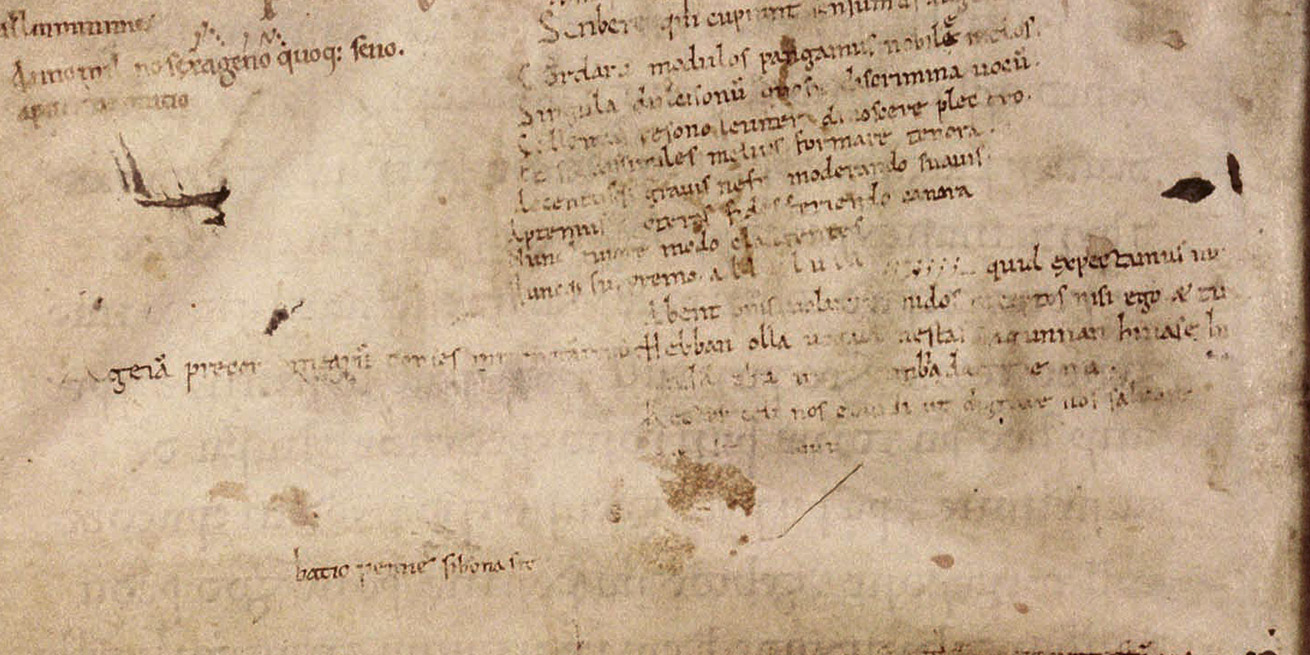

The verse Hebban olla vogala with the Latin translation above | Oxford, Bodleian Library, Bodley 340, fol. 169v

Hebban olla vogala

Traces of the Earliest Dutch

‘Hebban olla vogala nestas hagunnan hinase hic ande thu. Wat unbidan we nu?’ These scribbles on the last page of a manuscript containing Old English sermons are the oldest lines of poetry in Dutch. Put into present-day language: ‘Alle vogels zijn aan hun nesten begonnen, behalve ik en jij. Waar wachten we nog op?’ (All the birds have begun nesting, apart from me and you. What are we waiting for?)

There is unanimity about the meaning, but we can only guess at the origin of these verses. Possibly they are from a love song. A monk jotted them down to try out his pen, a new goose quill. He lived in a monastery in Kent in England, but probably came from the west of the county of Flanders. The lines were written at the end of the 11th century, but were not discovered until 1932.

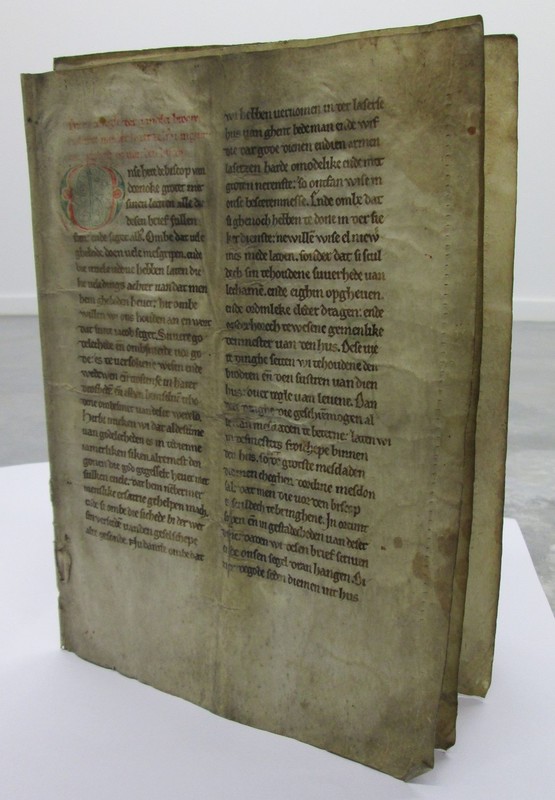

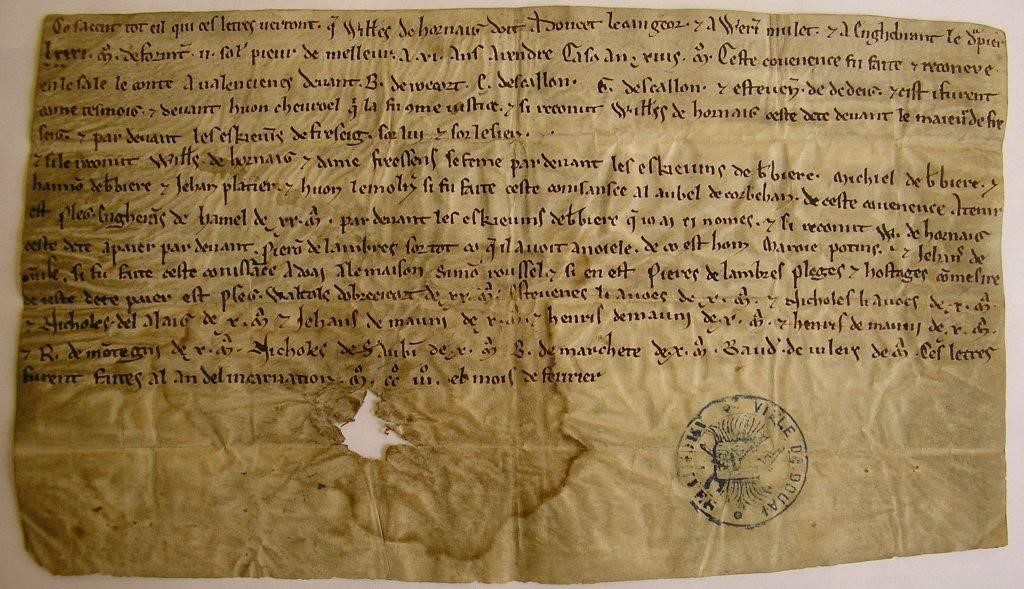

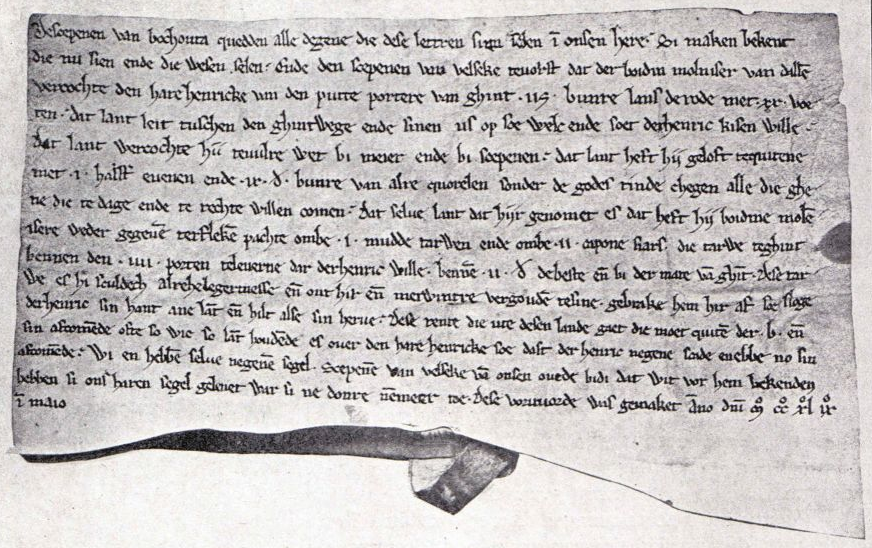

Oudenaarde, Archief OCMW, oorkonde nr. 542

This alderman’s letter from Bochoute is the oldest preserved Dutch-language property document (May 1249) which is not a translation from Latin. Boidin Molniser sells approx. 2.5 hectares of land to Henric van den Putte from Ghent, on condition that he cultivate it subject to payment of an annual rent of one hectolitre of wheat and two castrated cocks.

Traces of the Earliest Dutch

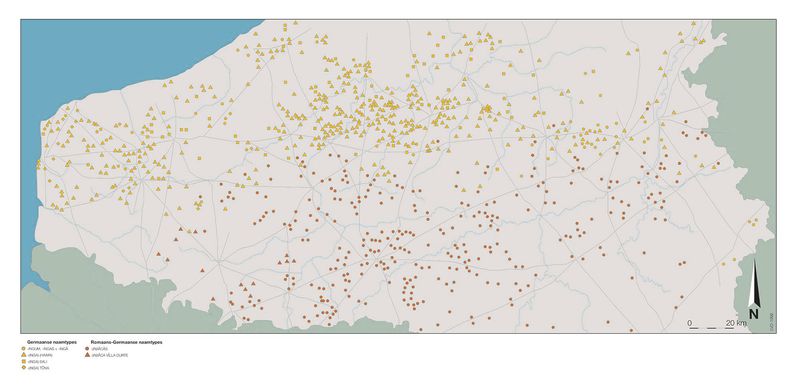

Hebban olla vogala may be the oldest piece of literature we know, but it is not the oldest surviving Dutch. Place names and personal names show traces of an even older Dutch. The zele in for example Vlierzele or Dadizele means ‘dwelling place’. Zaal is still used in Dutch in the meaning of ‘large room’. In the medieval name Adelbrecht, we recognise the words adel,which still exists, meaning ‘nobility’, and the word brecht, which has fallen into disuse, which meant ‘magnificent’.

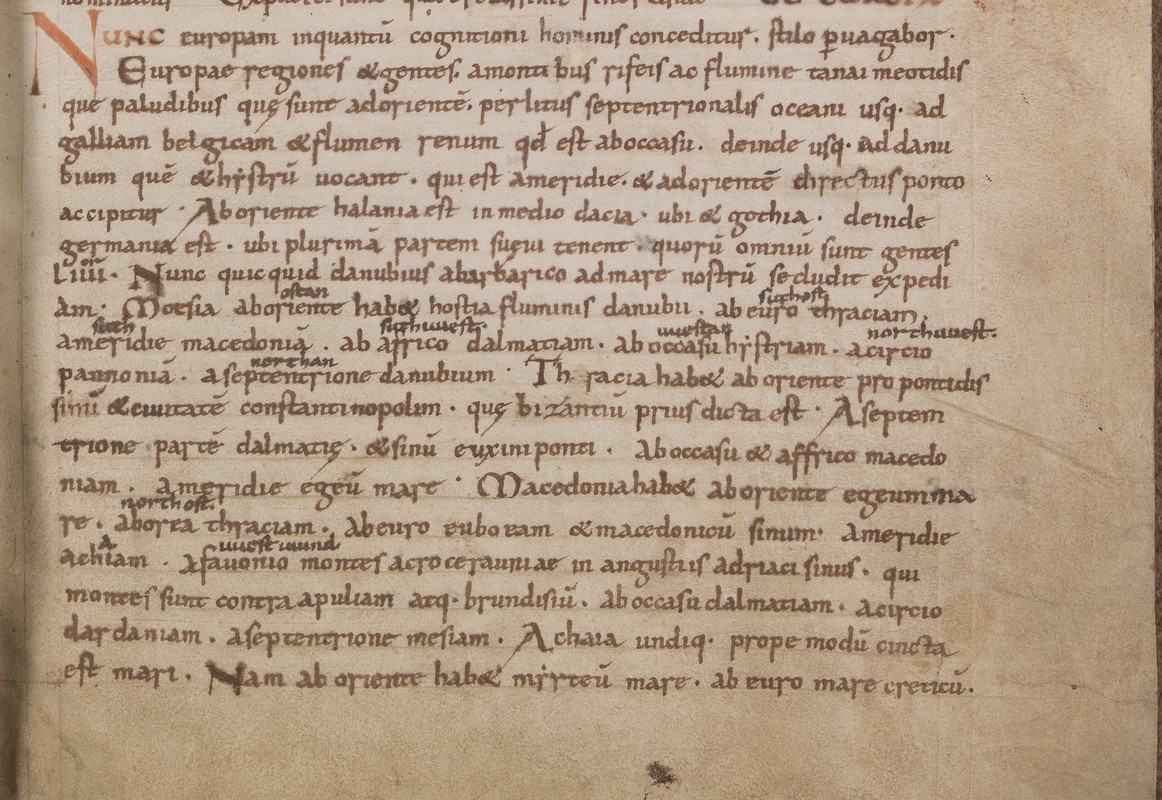

Researchers think that Old Dutch developed from West-Germanic from the beginning of the 5th century. The oldest words that we know, however, were not written down until the first half of the 8th century: these are the Old Dutch ‘glosses’, short definitions or translations of Latin terms, noted in the margin or between the lines. In addition, some Old Dutch incantations and legal formulas have been preserved. The longest text in Old Dutch is a commentary on a book from the Bible of about 1100.

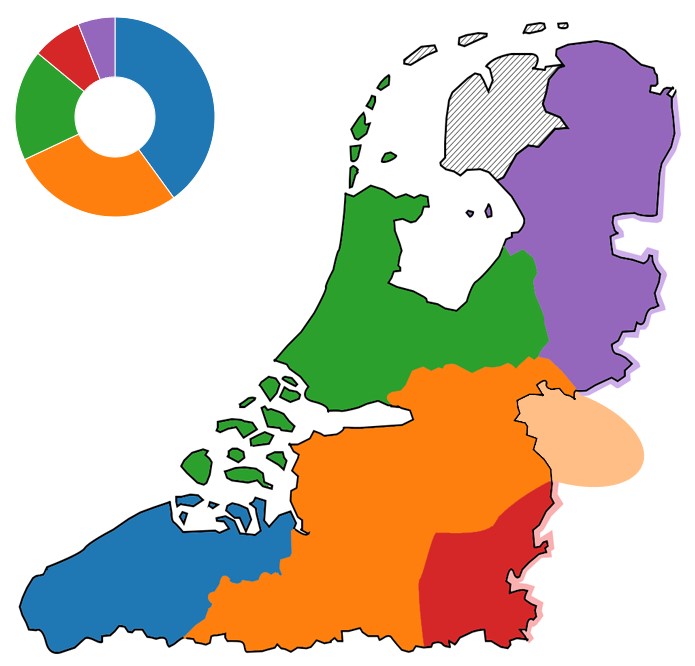

Old Dutch is in fact a collective noun for the Germanic dialects spoken in the Low Countries. In the second half of the 12th century Old Dutch underwent a number of important changes. Clear end vowels became duller: hebban became hebben, vogala became vogele. After that change we speak of Middle Dutch.

Focal points

Discover more on this topic

Non-fiction

Olla vogala: het verhaal van de taal van de Vlamingen, in Frankrijk en elders

Ed. Yoran, 2018.

Het verhaal van een taal: negen eeuwen Nederlands

Prometheus, 2003.

Het Nederlands vroeger en nu

Acco, 2011.

Hebban olla vogala: de mooiste liefdesgedichten uit de middeleeuwen

Bakker, 2002.

De taalgrens, of wat de Belgen zowel verbindt als verdeelt

Davidsfonds, 2012.

Schapenvellen en ganzenveren: het verhaal van het middeleeuwse boek

Davidsfonds, 1999. (12+)

15 eeuwen Nederlandse taal

Sterck & De Vreese, 2019.

Handgeschreven wereld: Nederlandse literatuur en cultuur in de middeleeuwen

Prometheus, 2002.

Stemmen op schrift. Geschiedenis van de Nederlandse literatuur vanaf het begin tot 1300

Bakker, 2006.

Het Nederlandse liefdeslied in de middeleeuwen

Prometheus, 2021.

Het verhaal van het Vlaams: de geschiedenis van het Nederlands in de Zuidelijke Nederlanden

Standaard Uitgeverij, 2003.