A standard mill from Vieil Rentier d’Audenarde, a land register from the end of the 13th century | Brussels, Royal Library of Belgium, MS 1175, fol. 15r

The Windmill of Wormhout

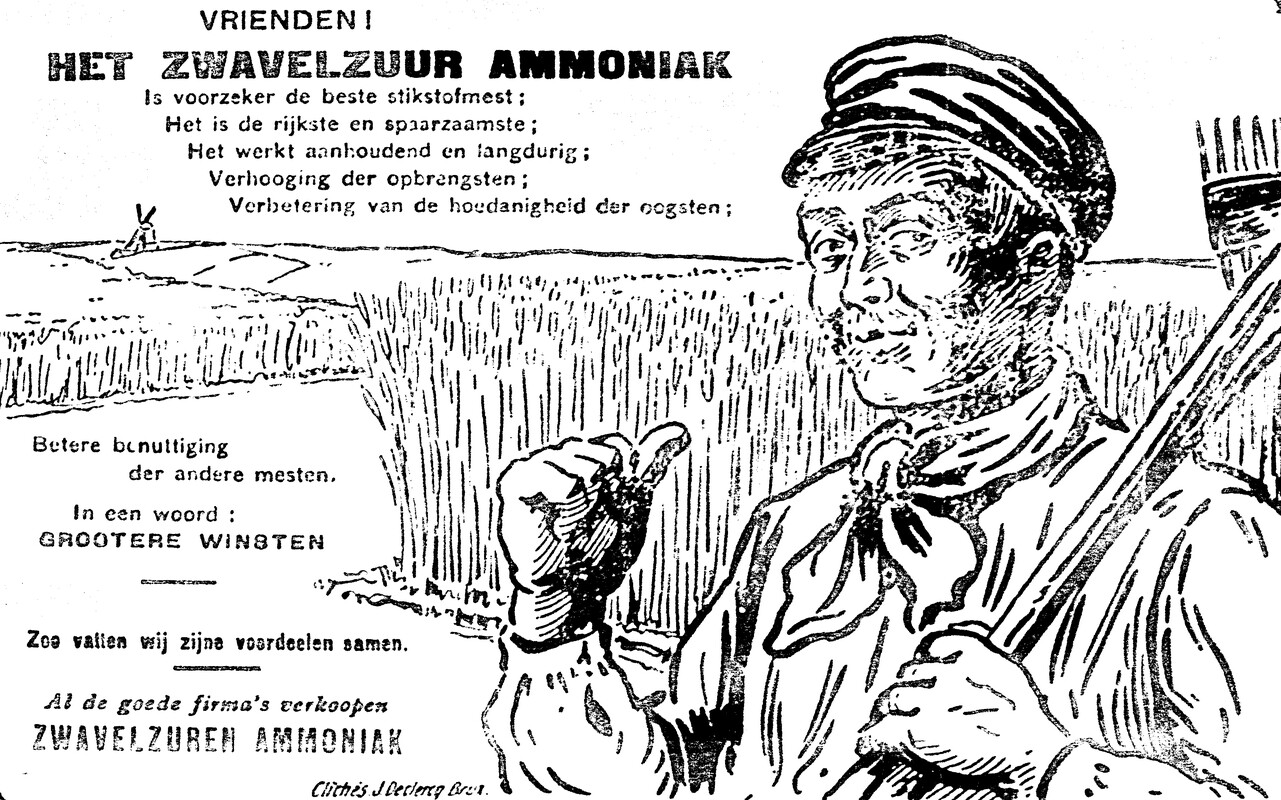

Innovation in Agriculture

‘In Wormhout [there is] a mill that is propelled by the wind,’ we read in a deed of the count of Flanders from about 1183. It is one of the very earliest mentions of a windmill in the North Sea area. The wooden constructions brought about a revolution in medieval agriculture.

Were they variants of watermills? Or vertical versions of the horizontal windmills from Asia and the Middle East? Historians and archaeologists have not yet found the answer. What we do know is that the standard millsmills placed on a wooden undercarriage which allowed the mill casing to be turned in the right direction, also called stake mills. like those in Wormhout in present-day French Flanders were complex machines that could turn completely around their own axis. With their sails they used the changeable wind to drive two millstones. They ground grain into flour. So that manual labour was no longer needed in regions where there was not sufficient height difference to grind with watermills – manual labour which was freed for other work. The standard mill was just one of the technological innovations which made the impressive population growth in medieval Western Europe possible.

Chantilly, Musée Condé, MS 65, fol. 3v

Turning plough and three-field system in the 15th century. From Les Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry (March), around 1410.

Innovation in Agriculture

Between the 11th and 13th centuries the population of Western Europe grew steadily, and in the Low Countries even more markedly than elsewhere. To be able to feed all those extra mouths, farmers started to innovate. They were able to work new land, increase fertility and achieve greater productivity for a given area of land.

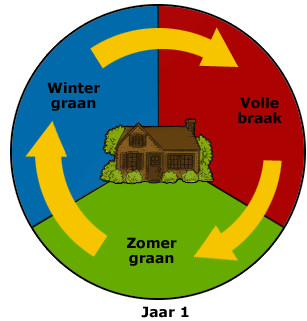

As elsewhere in Europe the three-field system farmers sowed both summer and winter grain, but left a portion of land to lie fallow each year, to avoid exhausting it, thus optimising the use of land. was introduced in the great agricultural domains, but in the Low Countries the intensification went further than that. Besides their own small fields farmers worked large central fields together intensively. They shared tools and draught animals. Systems of ditches drained land of excess water.

Farmers also grew more crops like peas and beans, which they sowed on fields that were lying fallow. Legumes were rich in protein and added nitrogen to the soil, which increased its fertility. Near the large towns industrial plants were grown, and plants from which dyes were prepared.

Innovation ensured more food production. Still, at certain times there was food insecurity and even famine. The poor were always the first victims. At the end of the Middle Ages grain had to be imported from Northern France and the Balticthe region on the Baltic Sea, present-day Poland, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. region, to feed the fast-growing population of the Low Countries, especially in towns.

Focal points

Discover more on this topic

Non-fiction

Eeuwen des onderscheids: een geschiedenis van middeleeuws Europa

Prometheus, 2020.

Het dagelijks leven in de middeleeuwen: de wereld van boeren, burgers, ridders en monniken

Tirion, 2001.

Leven in de middeleeuwen

Davidsfonds, 2000.

Middeleeuwse wetenschap 500-1500

Corona, 2014.

Zo was het vroeger… landelijk leven in Vlaanderen

Davidsfonds, 2004.

Tractor: een geschiedenis

AUP, 2018.

De middeleeuwers: mannen en vrouwen uit de Lage Landen, 450-900

Omniboek, 2020.

Landschap en landbouw in middeleeuws Vlaanderen

Gemeentekrediet, 1995.