Title page of the Code Civil, first published in 1804, the civil code drafted under Napoleon | Paris, Fondation Napoléon

The Napoleonic Code

The French Period

Kilometres and centilitres, the land registry and the status of notary: things that we take for granted today, come from the period of French rule. The Civil Code – the rules that govern the mutual interaction of Belgian citizens – also dates from the French period. For two centuries the Napoleonic Code from 1804 formed the basis of our civil law.

Napoleon himself called ‘his’ code his greatest achievement, more important than all his victories on the battlefield. With uniform legal rights for all he put an end to the old society from before the French Revolution.

When Belgium became independent in 1830, the Napoleonic Code remained in force. Gradually it became clear that many adjustments were necessary, particularly because the code was based on a father-spouse who ruled over his wife and children like a little emperor. Women gradually gained equal rights and children protection. A definitive break came in 2003 when Belgium as the second country in the world allowed people of the same sex to marry.

Washington, National Gallery of Art

In 1812 Jacques-Louis David painted Napoleon as a leader who is at work in his study until deep into the night for the French people. On the side table next to him are the texts of the Napoleonic Code.

The French Period

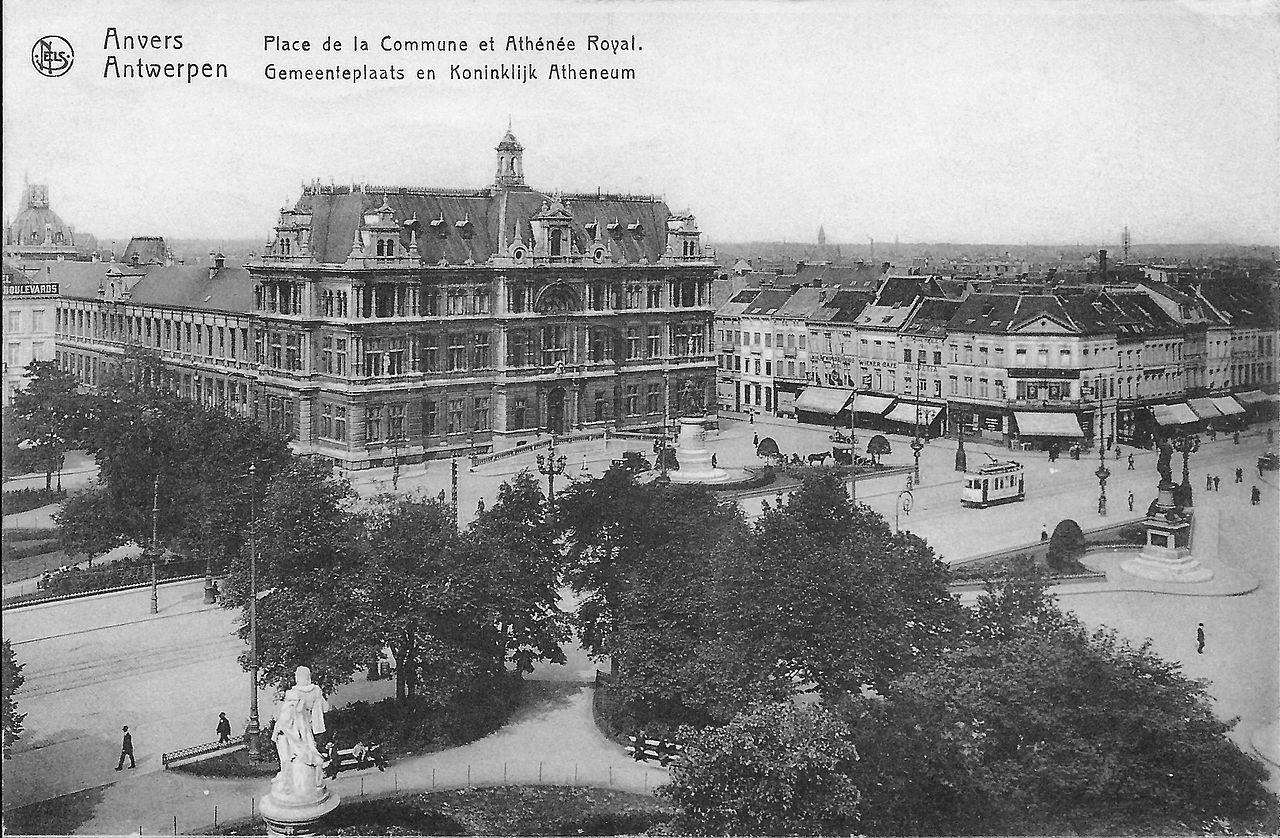

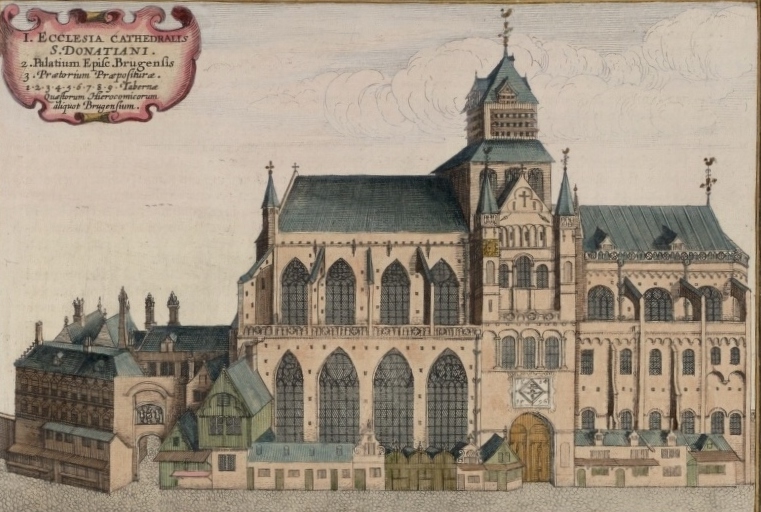

The French Revolution of 1789 had far-reaching consequences, not only for France, but for large parts of Europe and even beyond, in colonies like Haiti. Because in 1795 the Austrian Netherlands and the Prince Bishopric of Liège, together more or less present-day Belgium, were conquered and annexed, the revolutionary reforms applied here too.

The revolutionaries proclaimed freedom and equality and abolished noble privileges. They centralised the economic system, healthcare and education and made short shrift of local particularities. The old principalities were replaced by a new administrative division into départements, precursors of today’s provinces.

When general Bonaparte came to power in 1799 and five years later was crowned Emperor, he abolished some reforms of the revolution. He gave many others a lasting form, such as the registry of births, deaths and marriages and the decimal system. His civil code provoked a legal earthquake. Whereas before the coming of the French there was a chaos of local customs and legal rules, from now on the same law applied to everyone.

In 1815 Napoleon was defeated at Waterloo. The former Austrian Netherlands and the Prince Bishopric of Liège were added to the new Kingdom of the Netherlands and after the revolution of 1830 formed present-day Belgium. But many of the French reforms were lasting and the period of Gallicisation also left its traces.

Focal points

Discover more on this topic

Non-fiction

Het strijdtoneel van Europa: 1648-1815: De Zuidelijke Nederlanden onder Spaans, Oostenrijks en Frans bewind

Davidsfonds, 2019.

Revolutie in Antwerpen. De aquarellen van Pierre Goetsbloets (1794-1797)

Ludion, 2021.

België onder het Frans Bewind: 1792-1815

Gemeentekrediet, 1993.

Waterloo 1815-1914: de Europese erfenis van Napoleon

Houtekiet, 2014.

De Franse Revolutie 1 – Van revolte tot republiek

Horizon, 2022.

De Franse Revolutie 2 – Van Robespierre tot Napoleon

Horizon, 2022.

Napoleon 1: van strateeg tot keizer

Manteau, 2019.

Napoleon 2: van keizer tot mythe

Manteau, 2019.

Waterloo: de laatste 100 dagen van Napoleon

Manteau, 2013.

Napoleon: de schaduw van de revolutie

De Bezige Bij, 2019.

Met Napoleon naar Moskou: de ongelooflijke overlevingstocht van Joseph Abbeel

Davidsfonds, 2011.

Antihelden: bijzondere levens van gewone mensen uit de tijd van Napoleon

WBooks, 2015.

De fantoomterreur: revolutiedreiging en de onderdrukking van de vrijheid, 1789-1848

Uitgeverij Balans, 2015.

Fiction

Bakelandt

18 delen, Saga uitgaven, 2020. (stripreeks)

De voorspelling

Davidsfonds Infodok, 2009. (12+)

De vergissing

Davidsfonds Infodok, 2003. (12+)

Soldaat Marie

Clavis, 2018. (15+)

Rood

Manteau, 2010. (12+)

IJzerkop

Querido, 2019. (14+)

Boerenkrijg

(VRT, 1999).