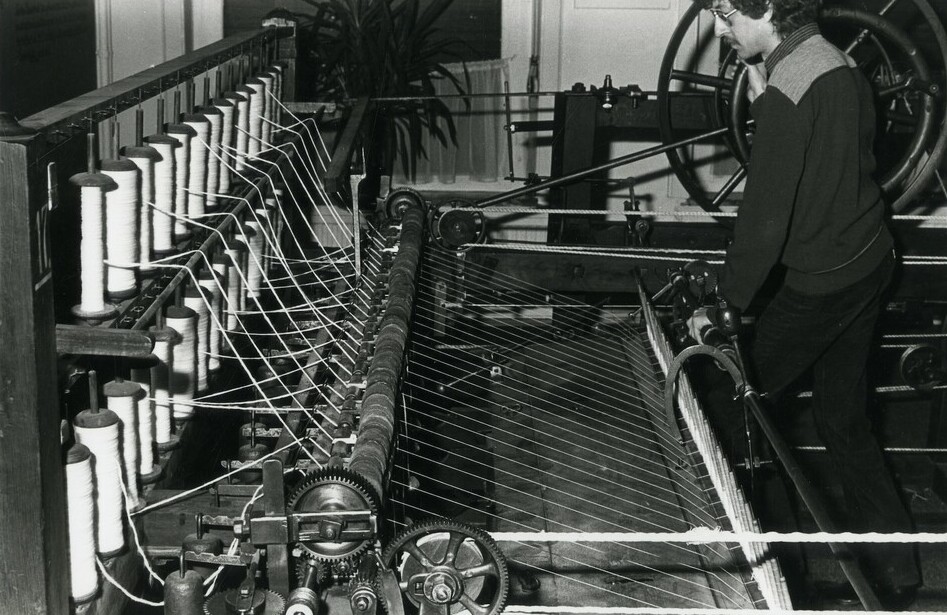

Mule Jenny from 1810. Oldest preserved specimen in the world | Ghent, Museum of Industry

The Mule Jenny

The Advent of Machines and Factories

The Mule Jenny caused a true revolution in the cotton industry: the machine could spin cotton almost two hundred times faster than a traditional spinning wheel. No wonder that the British tried to keep their invention secret as far as possible. Still, Lieven Bauwens from Ghent succeeded in smuggling a Mule Jenny onto the European continent.

Spinning cotton fibres into yarn was work that for a long time took place mainly in the English countryside. It was a labour-intensive process with which women on the farm supplemented their income from agriculture. It required ten spinners to produce enough yarn for one weaver. For that reason, in the 18th century systematic innovations took place designed to make spinning more efficient.

With the invention of the Mule Jenny in 1779 the Briton Samuel Crompton transformed the cotton industry. Spinning with a machine driven by steam power was not only much quicker, but the activity also transferred to great factory shops in new industrial towns like Manchester. Through the activity of Lieven Bauwens Ghent quickly followed the same route.

Ghent, Museum of Industry

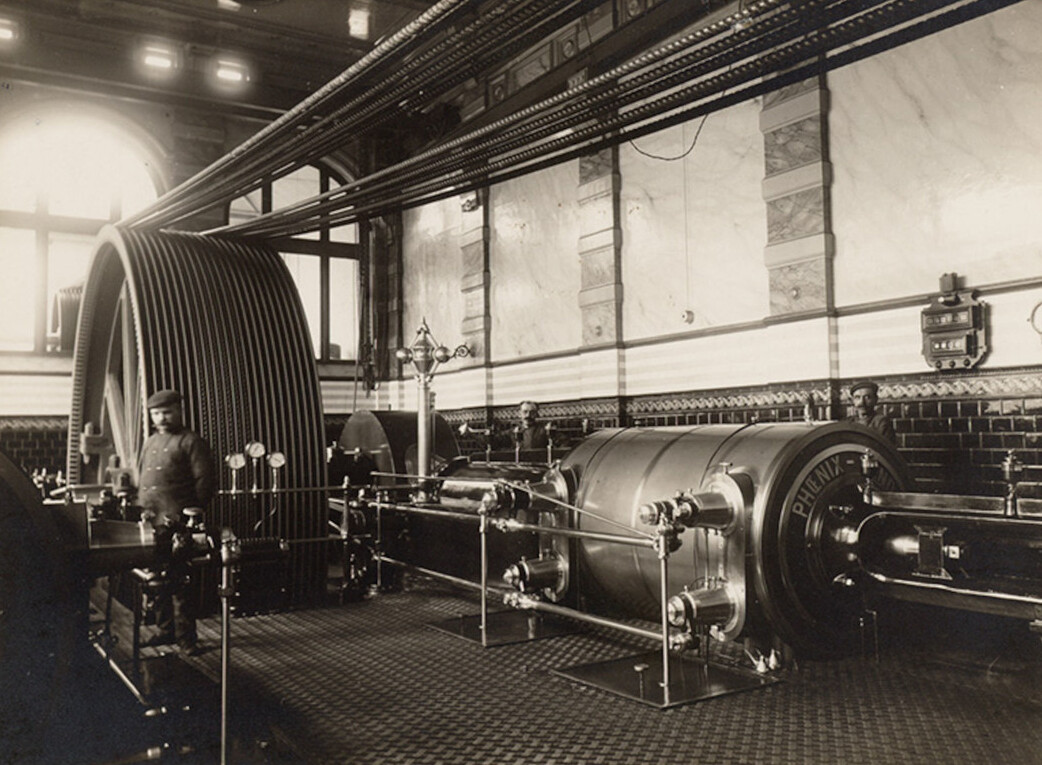

At the end of the 18th century the steam machine got the Industrial Revolution started. Until the First World War steam remained the principal driving force.

The Advent of Machines and Factories

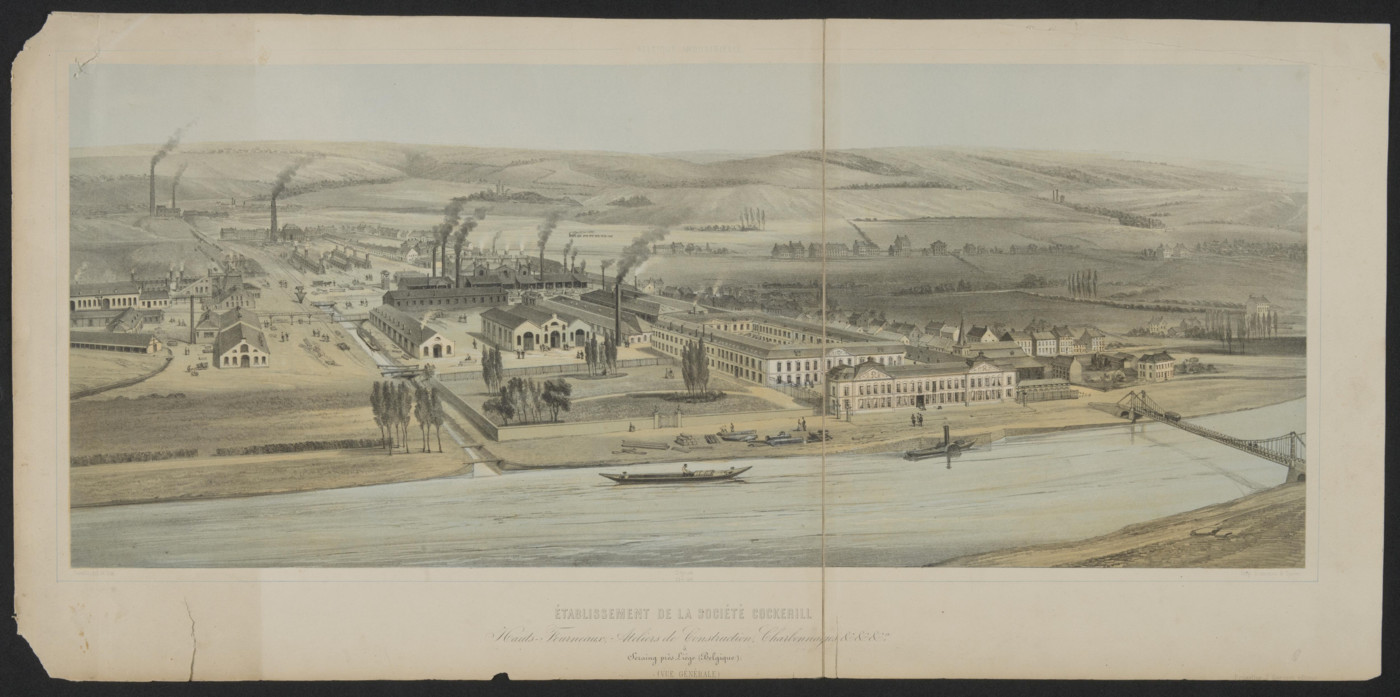

Large-scale production was not new. For example, the cotton industry in India and Chinese hemp spinning and iron manufacture were operating at a high capacity. But the mechanisation in the north-west of England in the second half of the 18th century was so radical that it marked the beginning of the industrial revolution. In the area around Manchester there was plenty of coal, the fuel for steam machines. Cotton could be easily brought in by sea and through the many canals. From North-West Europe the industrial revolution spread through the rest of Europe and ultimately the world.

Historians speak of a ‘revolution’ because the changes were ultimately so radical, not because they were that fast. Machines increased productivity and therefore also the wealth of the country.

The industrial revolution also changed ways of working, thinking and living. Machines were large and dependent on steam power, and so had to be located in factories. In this way people lost part of their independence. Instead of working at home they had to go to a factory, often in overpopulated towns. From now on machines determined the rhythm, which led to long working hours. For children particularly factory work was wretched.

At the same time the industrial revolution caused a shift in the balance of power within and between countries. For instance, it offered Great Britain the economic basis to become the leading power in Europe. Through industrialisation Europe was able to dominate world politics for two centuries.

Focal points

Discover more on this topic

Non-fiction

Katoen, de opkomst van de moderne wereldeconomie

Hollands Diep, 2016.

Gent. Stad van alle tijden

Mercatorfonds, 2016.

Het gestolde land. Een economische geschiedenis van België

Polis, 2016.

Ontdek ons industrieel erfgoed

Deltas, 2000.

Textiel: groots verleden, beloftevolle toekomst

Davidsfonds, 2017.

Kathedralen van de industrie

Borgerhoff & Lamberigts, 2021.

Wallonië, Tijdreis naar onze zuiderburen

2021.

Arm en Rijk

Unieboek/Het Spectrum, 1998.

De opkomst van de industrie 1700-1800

Corona, 2014. (12+)

Hier wordt gewerkt! Een kijk- en zoekboek doorheen ateliers

Pelckmans, 2021. (6+)

Waanzinnige uitvindingen op weg naar de moderne wereld: van ploeg tot printer

Corona, 2018. (9+)

Waarom de stoommachine geen Chinese uitvinding is. Hoe het Westen zo welvarend kon worden

Nieuw Amsterdam, 2013.

John Cockerill. Keizer van de industriële revolutie

Houtekiet, 2022.

Een kleine geschiedenis van grote durvers: buitengewone Belgische ondernemers van de middeleeuwen tot nu

Lannoo, 2020.

Fiction

Laat me gaan! Tijd van burgers en stoommachines

Zwijsen, 2020. (9+)

Voortman: de begindagen van de Gentse katoenindustrie: historiografische fictie

Academia Press, 2015.

De Avonturen van Suske en Wiske: De Hellegathonden (nr. 208)

Standaard, 1986.