Matthijs De Visch, Portrait of Empress Maria Theresia, 1749 | Bruges, Musea Brugge, Groeningemuseum

Empress Maria Theresia

Enlightenment in Europe

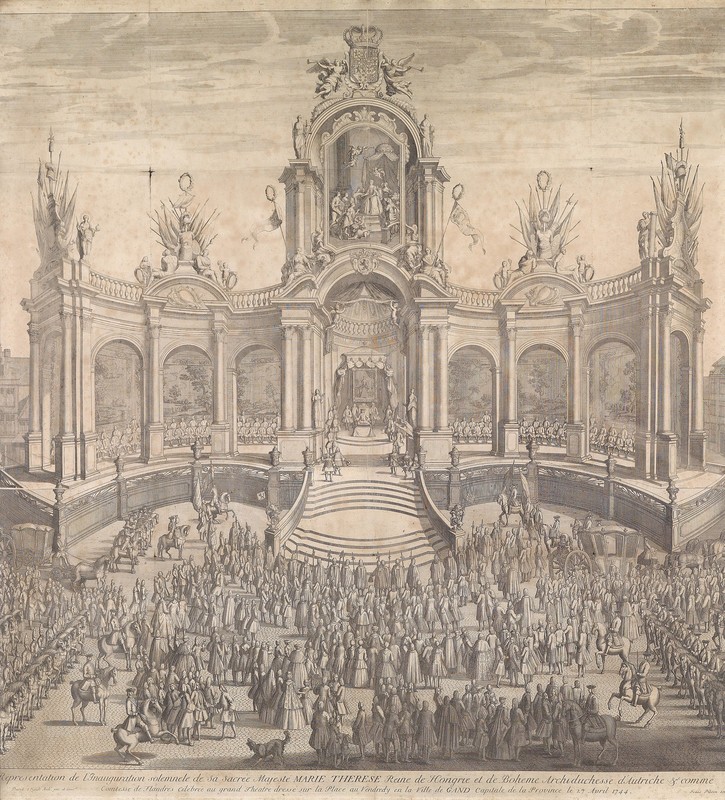

Members of the Habsburg dynasty ruled for more than six centuries over large parts of Europe. In all that time only one woman sat on the throne: Maria Theresia. For forty years she ruled (with her other domains) over the Austrian Netherlands.

In 1715 the southern part of the Low Countries passed from the Spanish to the Austrian branch of the Habsburgs. In 1740 Maria Theresia succeeded her father, when she was 23. As a woman she was not initially accepted by the great powers as heir to the throne.

Under her long rule the power of the central state administration grew, at the cost of the old counties and duchies. In economy, education and the judicial system Maria Theresia introduced reforms step by step. For example, she founded the Theresian high schools, the precursors of the athenaeums, with a uniform syllabus. Maria Theresia made her influence felt throughout Europe, also by pursuing a well-thought-out marriage policy for her numerous children.

Wikimedia Commons

The Martelaarsplein (square) (at the time Sint-Michielsplein) in Brussels was laid out in the 1770s in the Neo-Classical style, typical of the Enlightenment. The architect Claude Fisco (1736-1825), later a supporter of the Brabant Revolution, worked for the city.

Enlightenment in Europe

From the 16th century on scientific discoveries succeeded each other rapidly. As a result, confidence grew in the power of human reason. In the 18th century that led to a broad cultural and philosophical movement in Europe: the Enlightenment. Thinkers like Voltaire, Immanuel Kant and David Hume fought against political and social oppression and all kinds of superstition. They argued for a reorganisation of society.

Various monarchs were inspired by the Enlightenment, including Maria Theresia. But they refused to take these ideas to extremes, because that would undermine their own absolute authority. For example, the French philosopher Montesquieu had argued for the separation of legislative, executive and judicial power. Spreading power across a parliament, government and judges would strongly limit the power of a sole ruler. Jean-Jacques Rousseau, another French thinker, had actually put forward popular sovereigntythe principle that the highest authority lies with the people and a head of state must keep to laws and agreements with the population. as the basis of the state. The new radical ideas trickled slowly into the Austrian Netherlands.

The Enlightenment was to provide inspiration for two important revolutions at the end of the 18th century: the American Revolution of 1776 and the French of 1789. The revolutionaries proclaimed freedom and equality for all citizens, although it turned out in practice that people of colour and women remained in subordinate positions.

Focal points

Discover more on this topic

Non-fiction

Beter wordt het niet. Een reis door de Europese Unie en het Habsburgse rijk

De Geus, 2021.

Ondergang: de val van Habsburg in de Nederlanden (1648-1815)

Davidsfonds, 2022.

L’invention de la Belgique. Genèse d’un Etat-Nation (1648-1830)

Editions Racine, 2005.

Joseph II, catholique anticlérical et réformateur impatient

Editions Racine, 2007.

De eeuw van Jan de Lichte: misdaad, verraad en revolutie in de 18de eeuw

Vrijdag, 2020.

Democratische verlichting. Filosofie, revolutie en mensenrechten, 1750-1790

Van Wijnen, 2013.

Revolutie van het denken: radicale verlichting en de wortels van onze democratie

Van Wijnen, 2012.

The United States of Belgium. The Story of the First Belgian Revolution

Leuven University Press, 2018.

De Habsburgers. De opkomst en ondergang van een wereldmacht

Spectrum, 2021.

De weg naar het binnenland. Geschiedenis van de Nederlandse literatuur 1700-1800: de Zuidelijke Nederlanden

Bert Bakker, 2017.

Fiction

De bende van Jan de Lichte/De zoon van Jan de Lichte

De Arbeiderspers, 2007.

De Belgische republiek

Orion, 1978.

De eeuw van Jan de Lichte: misdaad, verraad en revolutie in de 18de eeuw

Vrijdag, 2020.

De Bende van Jan de Lichte

(2018)