An anonymous painter shows the Grand-Place in Brussels during an intense bombardment by the French army in the night of 13 and 14 August 1695 | Brussels City Museum

The Bombardment of Brussels

Wars in the Spanish-Habsburg Netherlands

From 13 to 15 August 1695 the French army bombarded the city of Brussels with a constant barrage of cannon and mortar fire. The military use of the action was secondary, sowing terror was the real aim. Because the bombardment had been announced in advance, the number of casualties was limited. But the lower town went up in flames, thousands of houses were destroyed and many artistic treasures were lost.

Since 1688 France had been in conflict with an alliance consisting of the German Empire, England and the Spanish kingdom. Wedged in between these great powers, the Spanish Netherlands were the stage on which the war, which dragged on, was largely fought out. With the attack on Brussels in 1695 the French army was trying to lure its adversaries away from the citadel of Namur, which was on the point of falling. However, the attempt was unsuccessful. The destruction of Brussels, a civilian target, turned out to be completely senseless. The international indignation was great. However, from the ashes of Brussels, which had been shot to pieces, there arose the monumental Grand-Place, which has meanwhile become a UNESCO world heritage site.

Antwerp, KMSKA Royal Museum of Fine Arts, www.artinflanders.be, photo Rik Klein Gotink

Maximiliaen Pauwels, The Proclamation of the Peace of Münster in the Market-Place in Antwerp in 1648, 1649

Wars in the Spanish-Habsburg Netherlands

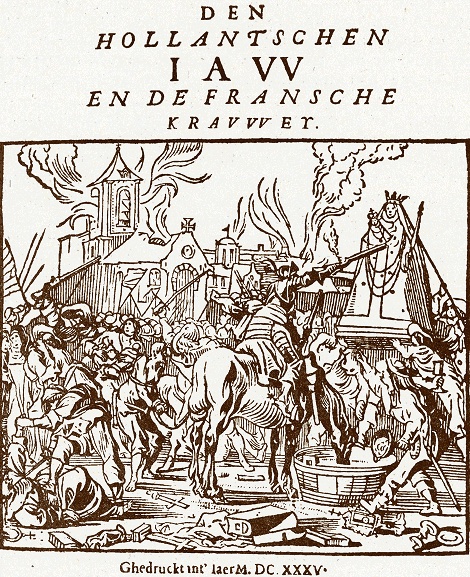

Since 1506 the Low Countries had belonged to the realm of the Spanish Habsburgs. When Holland and other northern territories broke away and at the end of the 16th century formed a separate Republicthis is the name for the Northern Netherlands until 1795. , Spain did not take it lying down. The result was a military conflict, and that was felt in the southern part of the Low Countries. In 1635, for example, the troops of the Republic and the French army invaded the Spanish Netherlands. They wanted to exclude Spain and divide up the area among themselves. In 1648 the Dutch Republic and Spain finally made peace, thus bringing an end to the so-called Eighty Years’ War. The border that was established in the Treaty of Münster, still accords more or less with the present Belgian-Dutch border.

Still a lasting period of peace was not achieved in the Low Countries. After 1648 there were constant tensions between Spain and France. In 1661 Louis XIV became king of France and managed in succeeding wars to seize large parts of the territory of the Spanish Netherlands. A tragic low point was the devastation of Brussels by the French. The new border that was created by these wars with France, largely coincides with the present Belgo-French border.

Focal points

Discover more on this topic

Non-fiction

Het strijdtoneel van Europa 1648-1815: de Zuidelijke Nederlanden onder Spaans, Oostenrijks en Frans bewind

Davidsfonds, 2019.

Historische atlas van Frans-Vlaanderen

Despriet, 1998.

Slagveld van Europa: duizend jaar oorlog in de Zuidelijke Nederlanden

Globe, 2007.

Een geschiedenis van Brussel

Lannoo, 2006.

België in de 17de eeuw: de Spaanse Nederlanden en het prinsbisdom Luik

Snoeck, 2006.

Oranje tegen de Zonnekoning: De strijd van Willem III en Lodewijk XIV om Europa

Uitgeverij Atlas Contact, 2016.

Bastions voor koning en God: forten en verdedigingswerken in het krekengebied van Oost-Vlaanderen

Provinciebestuur Oost-Vlaanderen, 2004.

De inname van Tienen 1635. Het drama van een grensstad

Uitgeverij Omniboek, 2023.

De Veertigjarige Oorlog 1672-1712: de strijd van de Nederlanders tegen de Zonnekoning

Prometheus, 2020.