The Belgian constitution came into force in 1831, and the oldest known Dutch translation (“Belgische Staetswet”) appeared alongside the French text in the Bulletin officiel (February 1831) | Brussels, Federaal Parlement

A Liberal Constitution

Belgium Independent

With the Belgian Revolution of 1830 the bourgeoisie gave expression to its aspiration for a national state with a liberal regime. That was embodied in the constitution which was approved in 1831 and remained unchanged for almost 140 years.

Two days after the Belgian revolutionaries had proclaimed independence on 4 October 1830, a committee of fourteen predominantly young jurists was entrusted with the task of putting together a proposed constitution. The constitution must legally enshrine the basic rights of Belgians and the foundations of the new state.

The committee drew its inspiration from, for example, the Dutch constitution of 1815, French models and British parliamentary traditions. After five sessions their work was done. Belgians were to enjoy a great many individual freedoms. Belgium became a parliamentary monarchy. Power was no longer vested in a king, but in the people, represented by an elected parliament. After a few minor adjustments the National Congress (the provisional parliament) approved the Belgian constitution on 7 February 1831.

Brussels, Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium

Gustaaf Wappers, Episode from the September Days of 1830 in the Grand-Place in Brussels, 1835.

Belgium Independent

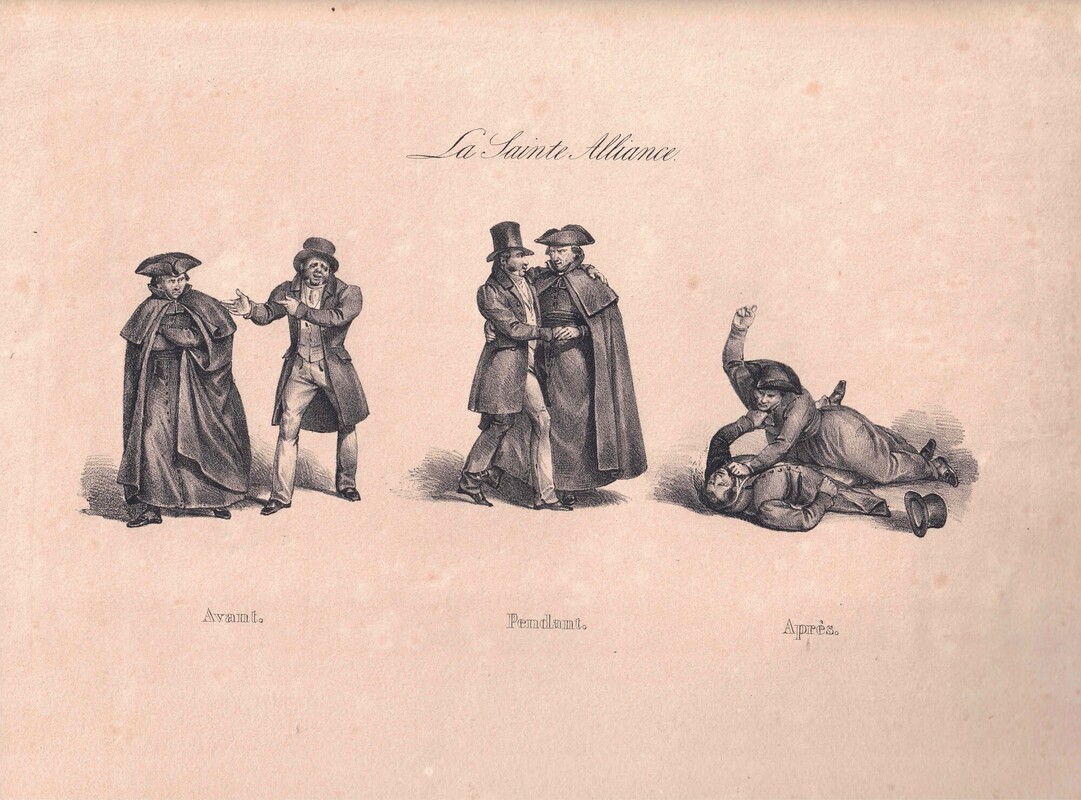

From 1815 to 1830 present-day Belgium and the Netherlands formed together the Kingdom of the Netherlands under Willem I. That kingdom was created by Great Britain and the other European powers which had defeated Napoleon. The new state was to serve as a buffer against future French attempts at expansion.

In the southern part of the young kingdom discontent quickly grew. The urban middle class wanted political accountability and freedom of the press, the Catholic church wanted less interference from government in education and the nobility wanted less taxes. Moreover, the Gallicised elite resisted the language policy of Willem I, who promoted Dutch in education and administration. When in 1830 food prices began to rise, the wider population also began to grumble.

In 1830 revolution broke out in Paris and a month later Brussels too revolted. The revolutionary flame spread like wildfire. A provisional government declared Belgian independence. The National Congress was elected to vote on a constitution.

In order to survive as an independent state Belgium needed the support of the great European powers, all of them monarchies. They were not keen on revolutionary experiments that would lead to a republic. For this reason the constitutional committee opted for a parliamentary monarchy. Since none of the great powers was to have too much influence over the new state, the German-British Leopold von Sachsen-Coburg took the Belgian throne as a compromise figure. But apart from that the constitution had strong liberal accents.

Focal points

Discover more on this topic

Non-fiction

Het (on)verenigd koninkrijk 1815-1830. Een politiek experiment in de Lage Landen

Ons Erfdeel, 2015

Leopold I. De eerste koning van Europa

De Bezige Bij, 2011.

Het verlies van België. De strijd tussen de Nederlandse koning en de Belgische revolutionairen in 1830

Horizon, 2019.

De erfenis van 1830

Acco, 2016.

Het verloren koninkrijk: het harde verzet van de Belgische orangisten tegen de revolutie 1828-1850

De Bezige Bij, 2014.

De constructie van België 1828-1847

LannooCampus, 2006.

Fiction

De vrouw met de luifelhoed

Kirjaboek, 2012.

De zon komt op in het westen

Kirjaboek, 2012.

De taal van de sterren

Kirjaboek, 2012.

Het land dat nooit was: een tegenfeitelijke geschiedenis van België

De Bezige Bij, 2015.