In some municipalities on the language border facilities are granted to those speaking a different language, as in the Flemish town of Ronse | Véronique Seynaeve

The Establishment of the Language Border

Belgium Becomes a Federal State

The political significance of the Dutch-French language border had for a long time remained limited. However, the aspiration of the Flemish movement to achieve a monolingual Flanders made the language border a subject of debate. In 1962 it was legally established. A year later this was followed by the demarcation of the bilingual Brussels agglomeration. That was the decisive step towards the federalisation of Belgium.

In order to resolve language conflicts it was decided between the two World Wars that the official language of administration, education and the law should coincide with the local language. From the 1930s on Dutch became the official language in Flanders and French in Wallonia. Brussels and the surrounding municipalities formed a bilingual agglomeration in the Dutch-language area. On the Eastern frontier a German-speaking areathe so-called Oostkantons, which Germany ceded to Belgium after the First World War as ‘compensation’. was created.

Every ten years a ‘language census’ was to be organised. On the basis of that municipalities and administrative language could change. Out of fear that those censuses, as in 1947, would be disadvantageous for the Dutch-speaking municipalities around Brussels, the Flemish movement lobbied for fixed language borders. They came about, after violent debates, in 1962-1963. Parliament established the border between the French- and Dutch-language areas and limited the bilingual Brussels area to nineteen municipalities. The division was of course artificial here and there: many border municipalities had inhabitants from both language groups.

Belga Image

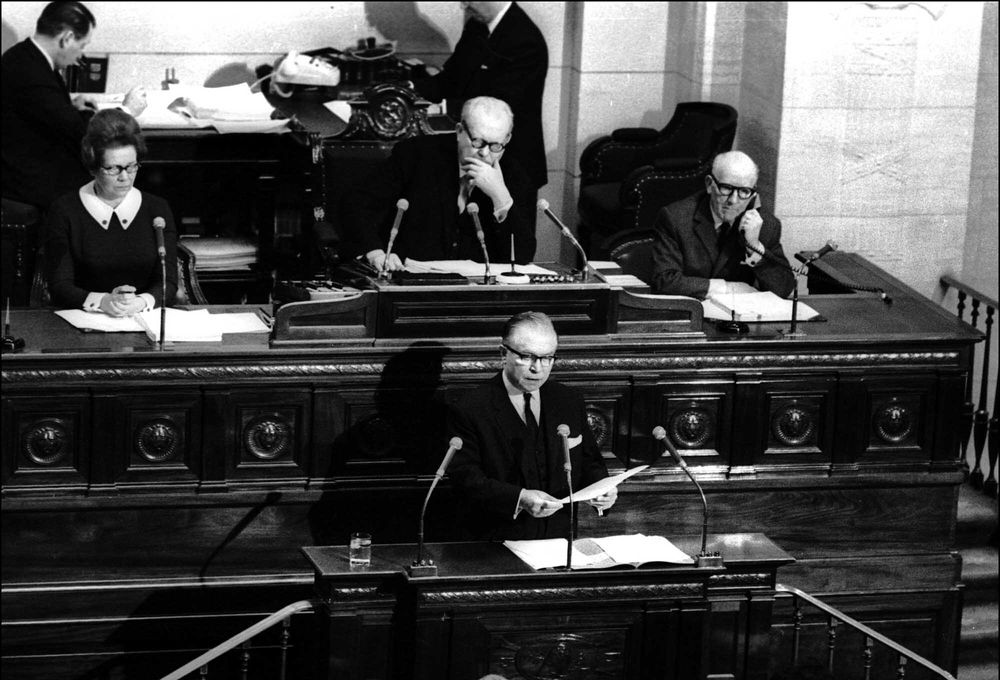

Premier Gaston Eyskens (1905-1988) informs members of parliament that the unitary state has had its day (1970). Eyskens had been campaigning since the 1930s for more Flemish autonomy.

Belgium Becomes a Federal State

After the ideological conflict between Socialists and Liberals on one side and Catholics on the other was settled by the Schoolpact of 1958, regional tendencies in the country gained more scope. As a result the Flemish-Walloon opposition gained in importance.

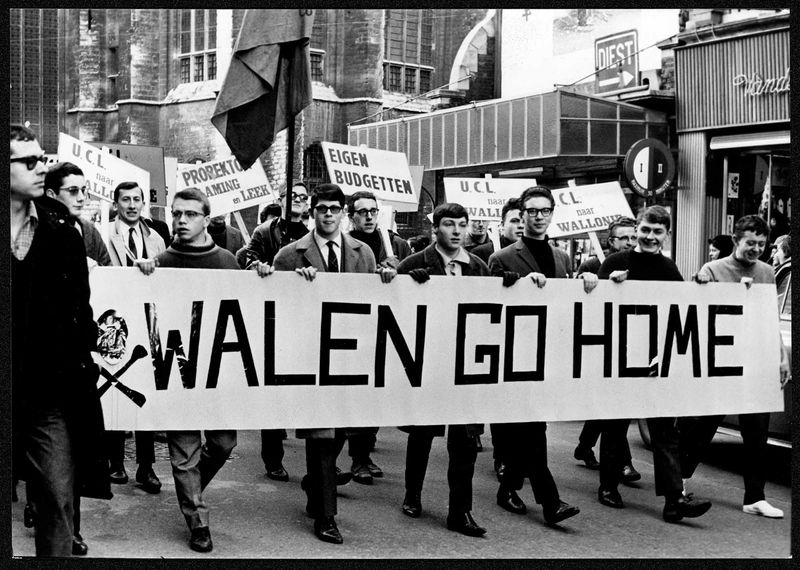

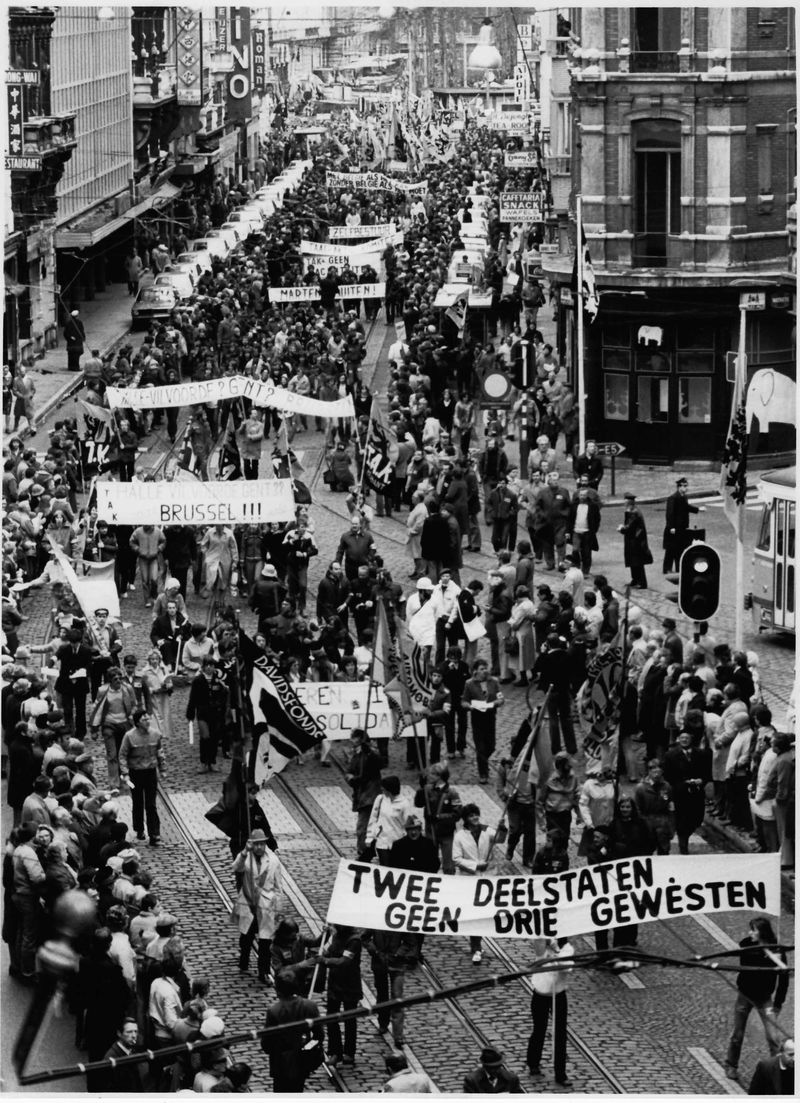

At the beginning of the 1960s many people considered a reform of the unitary state inevitable. The establishment of the language border was a step in that direction. In Flanders the cry for cultural autonomy had long been heard. On the Walloon side politicians and trades unions wanted the authority to ward off industrial decline. In addition, they were afraid of becoming a political minority in Belgium, because the Walloon population was stagnating. Parties such as the Volksunie, the Rassemblement Wallon and the Brussels Front démocratique des francophones (FDF) enjoyed success by championing their own language group or region. The agitation surrounding the splitting up of the bilingual University of Leuven gave extra momentum to the rising tensions between the Dutch and the French speaking communities.

In 1970 the government of Christian-Democrat Gaston Eyskens tinkered for the first time with the foundations of the Belgian state structure. The language border was constitutionally anchored. The Dutch-language, French-language and German-language Communities were given limited responsibilities for language, culture and education. In addition, a Flemish, Walloon and Brussels region was set up with economic powers. At the national level a number of measures guaranteed the balance of power between Flemings and French-speakers. Both groups were given the same number of ministerial posts.

The implementation of the reform led to new issues. The conviction grew that a more thorough modification of the state structure was necessary. In 1993, after a radical revision of the constitution, Belgium became officially a federal state, made up of three communities and three regions the so-called federated entities.

Focal points

Discover more on this topic

Non-fiction

Een geschiedenis van België voor nieuwsgierige kinderen (en hun ouders)

Atlas Contact, 2022.

Het onvoltooide land

Van Halewyck, 2009.

Vlaanderen, Brussel, Wallonië: Een ménage à trois

Epo, 2014.

Vijftig jaar Vlaams Parlement

Borgerhoff & Lamberigts, 2021.

De memoires. Luctor et emergo

Lannoo, 2006.

De taalgrens, of wat de Belgen zowel verbindt als verdeelt

Davidsfonds, 2012.

Wandelen langs de taalgrens

Contact, 2005.

Een geschiedenis van België

Lannoo, 2021.

Met dank aan de overkant: een politieke geschiedenis van België

Polis, 2017.

De memoires. Gedreven door een overtuiging

Lannoo, 2002.

De monarchie en ‘het einde van België’: een communautaire geschiedenis van Leopold I tot Albert II

Lannoo, 2008.

Taalgrens 50 jaar

Snoeck, 2013.