Steel operative at work on the blast furnaces of Sidmar, 1979 | Ghent, Amsab-ISG, Lieve Colruyt/rights SOFAM Belgium

Steel in Flanders

Economic Growth in the Sixties

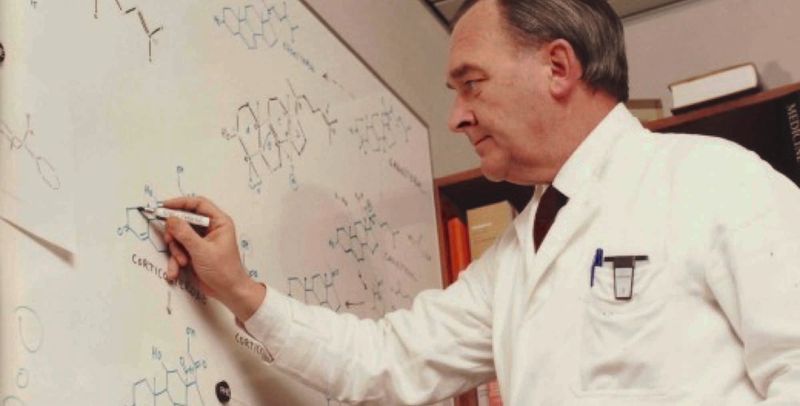

In 1967 the first steel sheets came off the rollers of the new Sidmar steel plant in Zelzate, the present ArcelorMittal. Steel had never before been produced in Flanders. The steel sheets were a symbol of renewed economic dynamism in the region.

Sidmar illustrated the shift of the economic centre of gravity in Belgium from the south to the north. In 1966 for the first time the gross domestic productthe added value of the production in a particular country/region, in one year. per inhabitant was higher in Flanders than in Wallonia. That shift had deeper underlying causes. The Walloon mining sector was not doing well. Raw materials for heavy industry in Wallonia had increasingly to be shipped from overseas. With its harbours Flanders had a great advantage, also in being able to export the finished products again easily.

Not only steel production was doing well in Flanders. The (petro-)chemical industry around the port of Antwerp was flourishing, as were car manufacturers like Ford Genk and General Motors, and pharmaceutical companies like Janssen Pharmaceutica.

Leuven, KADOC-KU Leuven. kfa026642

Industrial zone in Roeselare in the 1960s.

Economic Growth in the Sixties

In the 19th century Flanders had a limited industrial core. It consisted mainly of mechanised textile production in Ghent and some provincial towns. Around 1900 new branches of industry started to establish themselves in Antwerp and the Campine. They focused on new technologies, such as electricity, combustion engines or developments in chemistry, from the technology company Bell Telephone, to car builder Minerva, to Gevaert, the manufacturer of photographic paper.

However, it was especially after the Second World War that economic expansion in Flanders really gathered momentum. The setting up of the European Economic Community (EEC)predecessor of the European Union. made Flanders a central area in a gigantic market. In order to cope with the competition in that larger market, the Belgian government came up, at the end of the 1950s, with the so-called expansion laws. These contained a series of support measures for companies and regions to pump-start the economy and deal with structural unemployment, which was particularly high in Flanders.

The growth of the economy followed two spearheads. On the one hand large foreign multinationals found their way to Flanders. On the other hand, numerous dynamic small and medium-sized companies were set up. They found enough space in the new, well-equipped industrial estates that were built in almost every municipality.

Focal points

Discover more on this topic

Non-fiction

Ik was nog nooit in Zelzate geweest

EPO, 2010.

De biografie van André Leysen: met weloverwogen lichtzinnigheid

Lannoo, 2002.

100 jaar Niko: illuminating ideas

Lannoo, 2019.

Sidmar 1962-2002. 40 jaar staalproductie in Vlaanderen

Lannoo, 2002.

Turkije aan de Leie. 50 jaar migratie in Gent

Lannoo, 2014.

De golden Sixties: hoe het dagelijks leven in België veranderde tussen 1958-1973

Manteau, 2022.

Lernout & Hauspie / Top secret

Borgerhoff & Lamberigts, 2010.

Vlerick-boys: een Vlaamse meritocratie

Pelckmans, 2013.

Nieuw België, een migratiegeschiedenis, 1944-1978

Lannoo, 2021.

IJzersterk: de geschiedenis van de Vlaamse metaalindustrie

AMSAB, 2018.

‘On est là’. De eerste generatie Marokkaanse en Turkse migranten in Brussel 1964-1974

Garant, 2014.