Jacques Brel sweeps the audience at L’Olympia (Paris) off its feet | Belga Image, 50307080

Le plat pays of Jacques Brel

French-Language Culture in Flanders

In 1962 Jacques Brel sang of the North Sea, the Scheldt and the wet, grey skies in Le plat pays. The song remains one of the most beautiful odes to the Flemish landscape. With the Flemings themselves the Brussels chansonnier maintained a complex relationship.

Sam Cooke, Marlene Dietrich, Frank Sinatra, David Bowie, Nina Simone: Jacques Brel has been covered by the true greats, and closer to home by Liesbeth List and Will Ferdy. In Flanders the French-language singer with West-Flemish roots won over hearts with Le plat pays and Marieke. He also issued those songs about his love for ‘Vlaanderenland’ in Dutch. In other numbers Brel dared to make fun of the good old, Catholic Flemings. Les Flamandes (1959), La La La (1967) and Les F[lamingants] (1977), with criticism of Flemish nationalists, went down badly. In Flanders, where French always sounded more chic than Dutch, Brel’s satire hit a touchy nerve. For some he remained a ‘franskiljon’, a term of abuse for a Gallicised Fleming.

Ghent, MSK Museum of Fine Arts

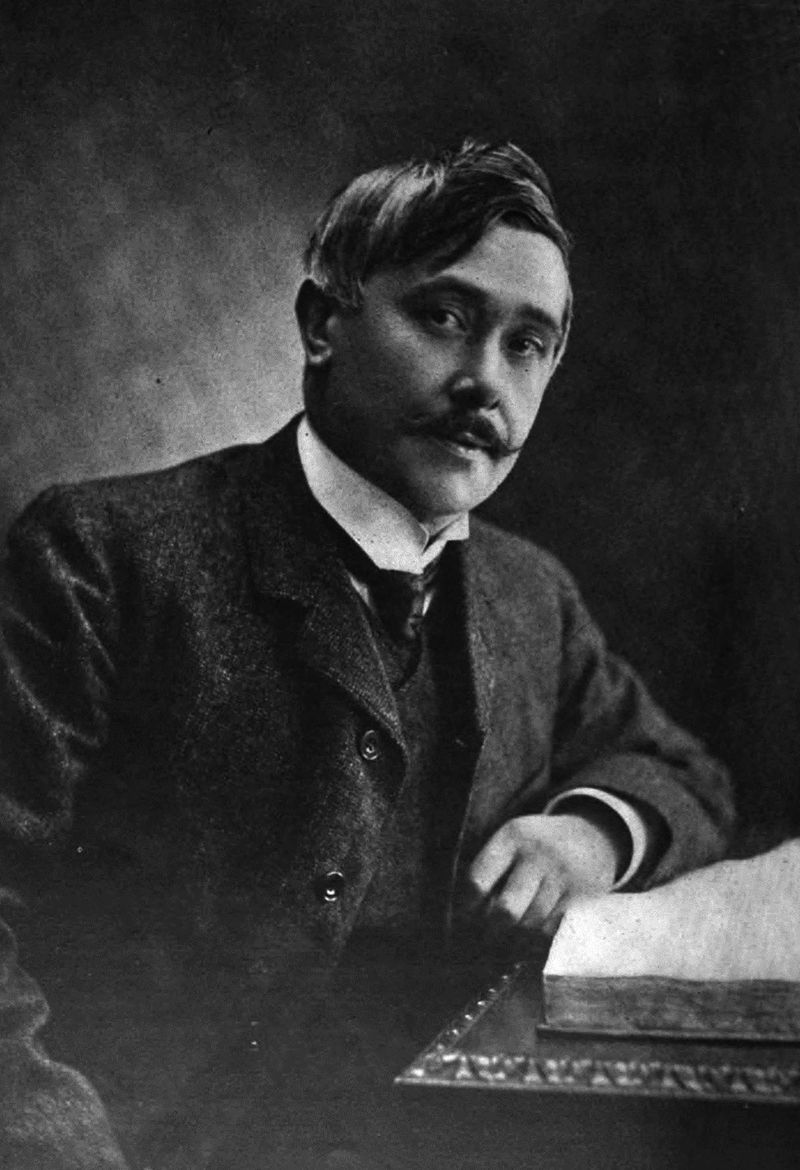

Théo van Rysselberghe, The Lecture by Emile Verhaeren, 1903. Emile Verhaeren is dressed in red. Maurice Maeterlinck is also in the audience (far right).

French-Language Culture in Flanders

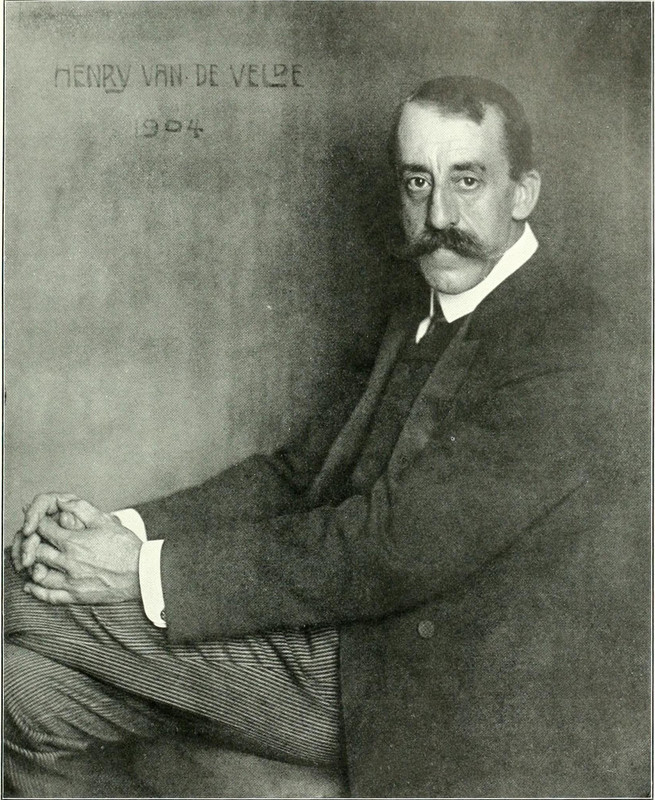

Jacques Brel called himself ‘un Flamand qui parle français’. In so doing he was claiming a place in a long tradition of French-speaking artists who embraced a Flemish identity.

In the 19th century French was the everyday language, not only in the south of Belgium but also in higher circles in Flanders. Even after the Flemish movement scored its first successes, the bourgeoisie generally continued to opt for French.

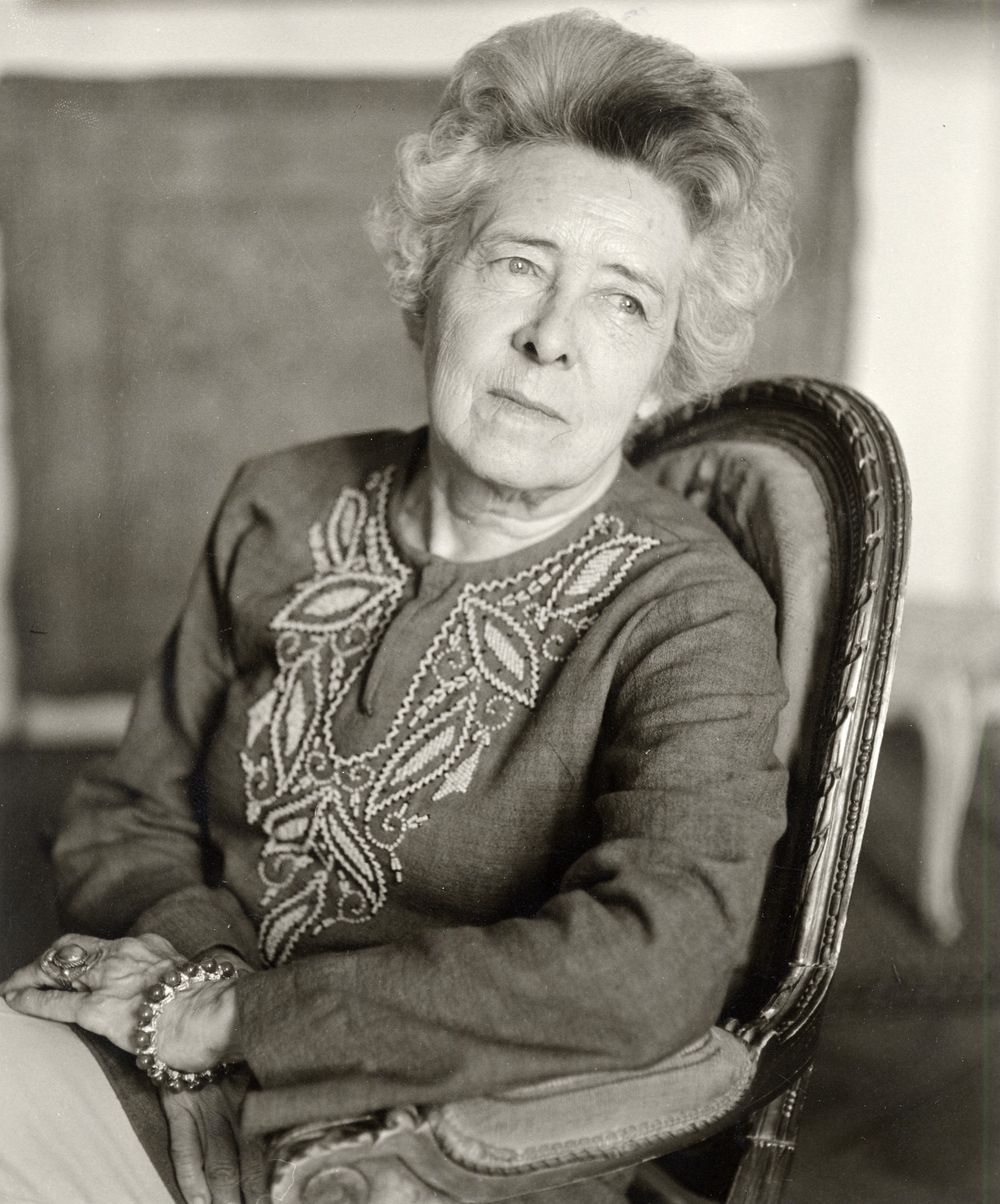

French-language authors, like Brel, often harked back in their work to the Flemish landscape where they grew up. They also sought inspiration in the medieval past, in the folklore or the painting of the Low Countries. Flanders was often more a poetic concept than a historical or political reality. Around the turn of the century French literature in Flanders reached its zenith. The Ghent-born Maurice Maeterlinck won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1911. He was particularly praised for his theatre. The poet Emile Verhaeren was rated at least as highly internationally.

The division between French-language and Dutch-language culture was far from strict. The French-speaking Antwerpian Georges Eekhoud, for example, wrote the first biography of Hendrik Conscience. Such contacts diminished in the first decades of the 20th century with the advance of Dutch in Flanders. When Jacques Brel scored his greatest successes after the Second World War a ‘Flamand qui parle français’ was no longer as natural a phenomenon as in the 19th century.

Focal points

Discover more on this topic

Non-fiction

Jacques Brel: de passie en de pijn

Olympus, 2003.

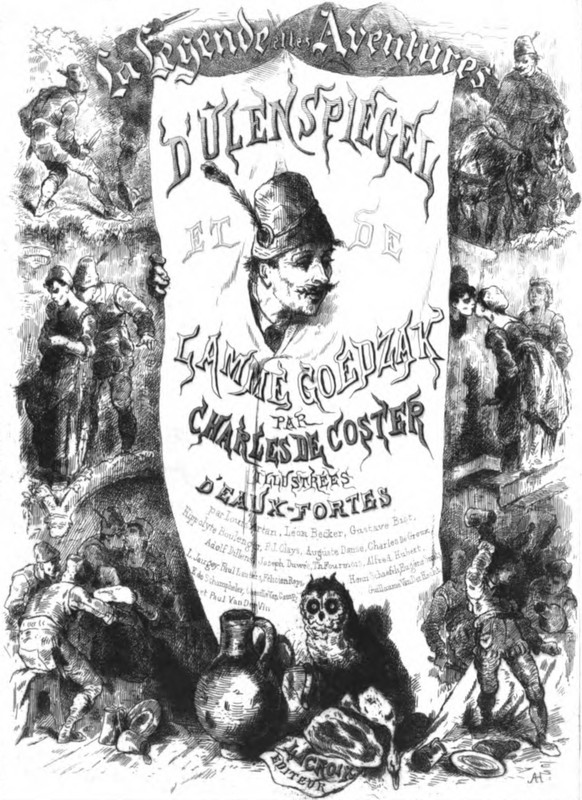

Held voor alle werk. De vele gedaanten van Tijl Uilenspiegel

Houtekiet, 1998.

Van Reynaert de Vos tot Tijl Uilenspiegel: op zoek naar een canon van volksboeken 1600-1900

Walburg, 2014.

Uilenspiegel. De wereld op zijn kop

Davidsfonds, 1999.

De Fransschrijvende Vlamingen als cultuurdesem

- Tijdschrift over de geschiedenis van de Vlaamse beweging, 1996, p. 111-126.

Schurk of schelm? Uilenspiegel 500 jaar actueel

Openbaar Kunstbezit in Vlaanderen, 49 (2011), nr. 4, p. 20-24.

Jacques Brel: de definitieve biografie

Houtekiet, 2012.

Jacques Brel: een leven

Horizon, 2018.

Fiction

Ne me quitte pas. Laat me niet alleen

Nijgh en Van Ditmar, 2004. (selectie Brel-teksten)

Uilenspiegel

De Bezige Bij, 1965.

De legende van Uilenspiegel

Davidsfonds, 2017.

Jerom. De wraak van Tijl (nr. 29)

Standaard Uitgeverij, 1988.

Suske en Wiske. De Krimson-crisis (nr. 215)

Standaard Uitgeverij, 1988.

Tijl: roman

Querido’s Uitgeverij, 2017.

Dansen op een koord

Zwijsen, 2007. (6+)

Tijl Uilenspiegel

Zwijsen, 2001. (9+)

Tijl Uilenspiegel

De Vier Windstreken, 2000. (6+)

Tijl Uilenspiegel

Averbode, 2000. (12+)

Tijl Uilenspiegel

Uitgeverij Vrijdag, 2022.

De Geuzen

Standaard Uitgeverij, 1985-1990. (stripreeks).

Tijl Uilenspiegel 1. De opstand der Geuzen

Standaard Uitgeverij, 1955.

Tijl Uilenspiegel 2, Fort-Oranje

Standaard Uitgeverij, 1954.

Nu kijken

Meer kijk/luister materiaal

J’aime les Belges

(2008)

Tijl Uilenspiegel. De legendarische deugniet

(2003)

Audioboek