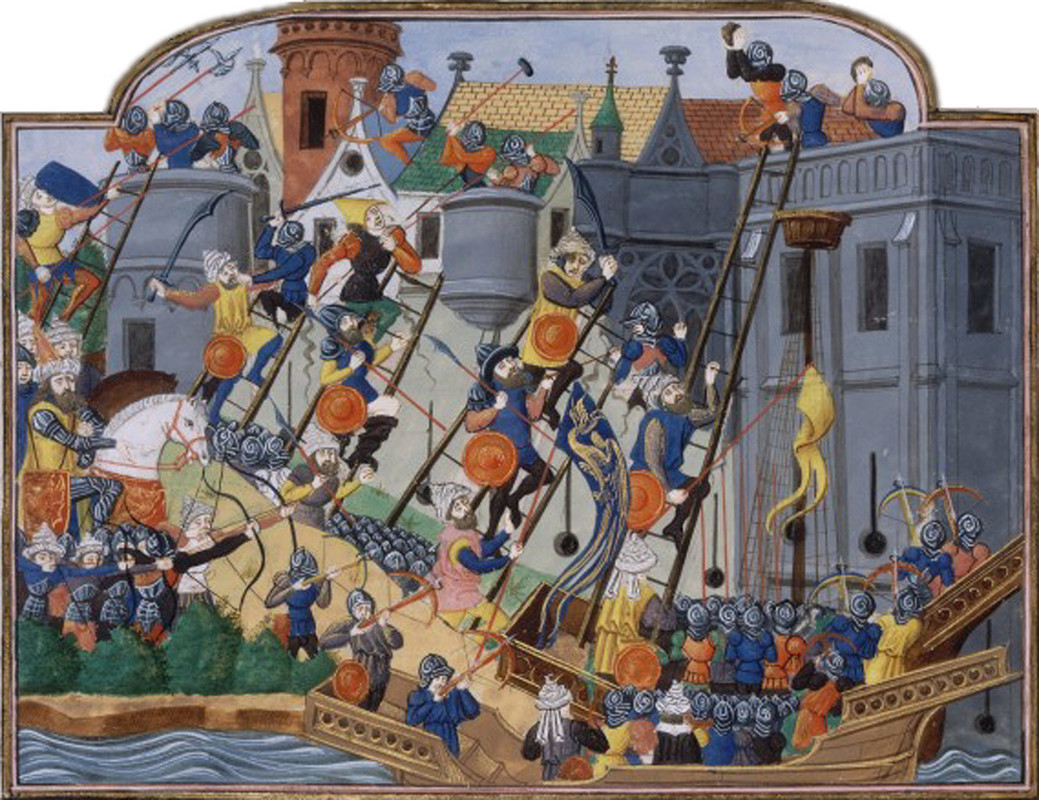

The Ghent magistrates beg Philip the Good for mercy after the Battle of Gavere. Miniature of about 1454 | Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek

The Battle of Gavere

The Burgundians

On 23 July 1453 Ghent militias advanced on Gavere to attack the army of the Duke of Burgundy. When their own supply of gunpowder threatened to blow up, the men of Ghent scattered. Many fleeing soldiers jumped into the Scheldt and drowned, others were killed. The Burgundians defeated the Ghent troops and so were able to strengthen their position in the Low Countries.

The towns in the county of Flanders had built up a lot of power. They enjoyed a great deal of freedom and could take a relatively independent attitude to their rulers. This was not to the liking of the ambitious Burgundian duke Philip the Good, who wanted to centralise power as far as possible on the Burgundian court. Concerned about the retention of their autonomy, the towns rebelled against the duke.

Of all the rebellious townspeople the Ghent tradespeople were the most persistent. In 1451 their intransigence led to open war with Philip the Good. The battle of Gavere was the culmination of that long struggle. Because of its defeat Ghent had to relinquish a large part of its traditional freedoms.

Chroniques de Hainaut, Brussels, Royal Library of Belgium, MS 9242, fol. 1r

This miniature by Rogier Van der Weyden shows a writer presenting a book to Philip the Good. The Burgundian dukes built a huge collection of books: the Library of Burgundy. Their library laid the foundation for the present Royal Library of Belgium.

The Burgundians

The Burgundian dukes were in fact vassals of the French king, but in the late Middle Ages began to steer an independent course. A marriage between Philip the Bold of Burgundy and Margaret of Male, daughter of the count of Flanders, also gave them a firm base in the Low Countries. When the Flemish count died in 1384, Philip the Bold gained authority, via his wife, over the wealthy and highly urbanised Flanders.

Using a well-planned marriage policy, purchases and wars the Burgundians systematically expanded their territory. Philip the Good, grandson of Philip the Bold, particularly, acquired a considerable area. He subjected a large number of principalities to his authority and so achieved the political unification of a large part of the Low Countries. Only the Prince-Bishopric of Liège, with the county of Loon, remained beyond his grasp. In the 15th century the Burgundian empire grew into a new great power, squeezed between France and the German territories.

Philip the Good did not want to rule only in name over his territories, he wanted direct control. To achieve that aim, he needed an extensive court, judges and officials, and stable tax incomes to be able to pay all those people. Thus began a process of centralisation and state building which – despite repeated resistance from his subjects – gradually put an end to the autonomy and privileges of the towns of the Low Countries.

Focal points

Discover more on this topic

Het verhaal van Vlaanderen – Zwarte dood en gouden tijden

Bron: VRT archief, De Mensen – 29 jan 2023

Het verhaal van Vlaanderen – Zwarte dood en gouden tijden

Bron: VRT archief, De Mensen – 29 jan 2023

Het verhaal van Vlaanderen – Zwarte dood en gouden tijden

Bron: VRT archief, De Mensen – 29 jan 2023

Non-fiction

Vlaamse miniaturen 1404-1482

Davidsfonds, 2011.

De wereld van de Bourgondiërs: 1363 – 1477

Bekking & Blitz, 2011.

De Bourgondische vorsten, 1315-1530

Davidsfonds, 2008.

Graven van Vlaanderen. Vlaamse vorsten in woord en beeld

Walburgpers, 2013.

Karel de Stoute (1433 – 1477): pracht en praal in Bourgondië

Mercatorfonds, 2009.

Gouden tijden: rijkdom en status in de middeleeuwen in de Zuidelijke Nederlanden

Lannoo, 2016.

De Bourgondiërs. De Nederlanden op weg naar eenheid 1384-1530

Meulenhoff, 1997.

De Bourgondiërs. Aartsvaders van de Lage Landen

De Bezige Bij, 2019.

Fiction

Op een wit paard

Averbode, 1993. (12+)

Floris en Belle

Averbode, 2000. (12+)

Een masker van ijs

Meulenhoff, 1987. (12+)

De laatsten der Bourgondiërs: roman over Filips de Goede en Karel de Stoute

Conserve, 1993.

Een ridderzaal zonder ridders

Syndikaat, 2018. (Stripverhaal, 9+)

Suske en Wiske. De verloren Van Eyck (nr 351)

Standaard Uitgeverij, 2020.

Jonkvrouw

Facet, 2005. (14+)