The Mystic Lamb by Jan and Hubert van Eyck, 1432 | The Mystic Lamb, Jan and Hubert van Eyck, St Bavo’s Cathedral Ghent, www.artinflanders.be, photo Hugo Maertens and Dominique Provost, CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0

The Adoration of the Mystic Lamb by the Van Eyck Brothers

Medieval Iconography

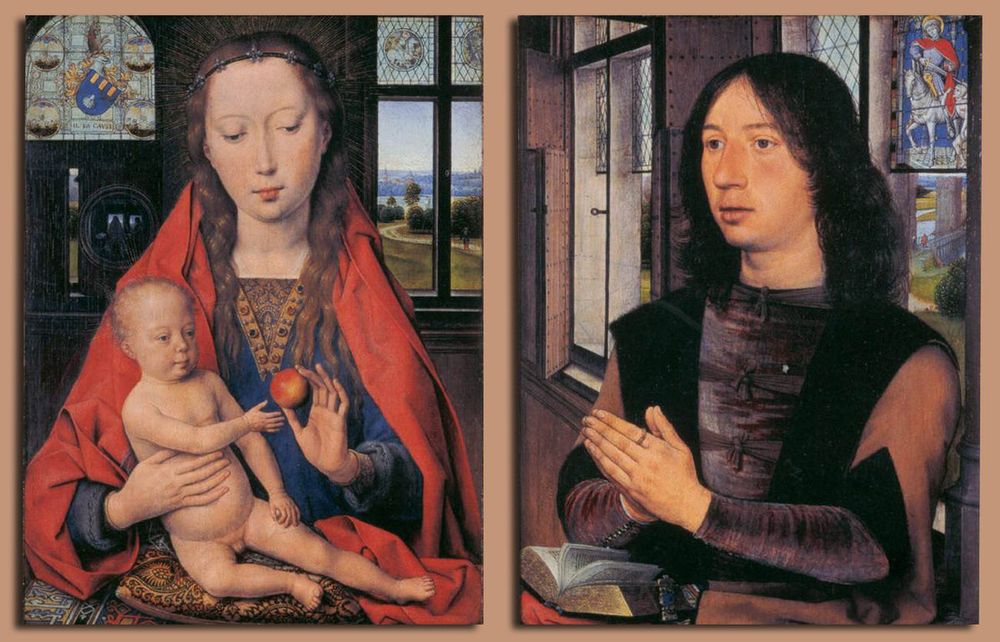

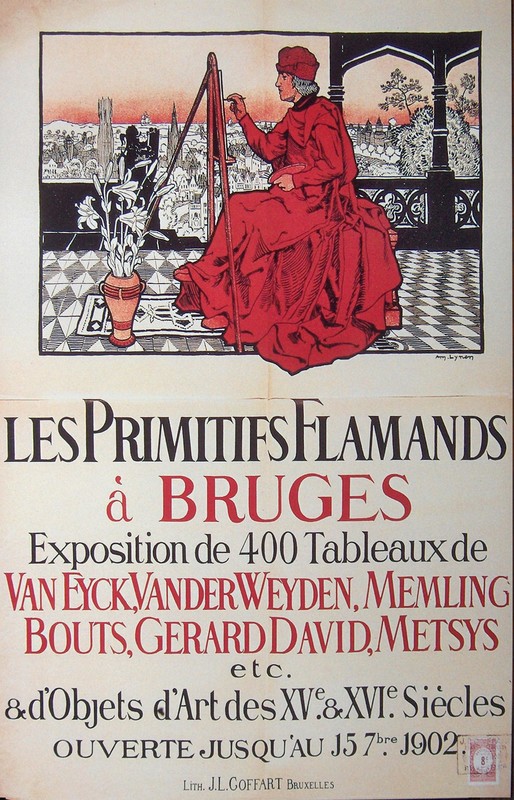

The Adoration of the Mystic Lamb is one of the most famous paintings in the history of Western art. Hubert and Jan van Eyck made the monumental triptych between 1424 and 1432. The painting is an iconic example of the works of the so-called Flemish Primitives, a group of painters to which the Van Eyck brothers are assigned.

The painting contains hundreds of figures in paradisial surroundings with a wealth of plants and flowers. Everything is depicted realistically. The title comes from the scene at the bottom of the picture in which the Mystic Lamb is depicted on an altar. In Christianity the lamb stands for Jesus Christ, who gave his life to redeem mankind from its sins.

Hubert van Eyck began the painting. After his death in 1426 his younger brother Jan completed it. The commission came from a rich nobleman from the Waasland, the Ghent alderman and church warden Joos Vijd and his wife Elisabeth Borluut. It was to serve as an altarpiece for their private chapel in the Saint-John’s Church in Ghent, the present-day Saint-Bavo’s Cathedral, where it can still be seen.

The Mystic Lamb, Jan and Hubert van Eyck, St Bavo’s Cathedral Ghent, www.artinflanders.be, photo Hugo Maertens and Dominique Provost, CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0

Het Lam Gods van Jan en Hubert van Eyck, rond 1430.

Medieval Iconography

The Mystic Lamb depicts an important theme of Christianity. For medieval Christians the meaning of such religious paintings was usually clear. Many of today’s viewers no longer understand the iconography.

The art work shows what virtues man must have to enter heaven and there to see the Mystic Lamb, which is a symbol of the Saviour Jesus Christ. The judges point to justice and the hermits to moderation. In the three central upper panels Mary and John the Baptist plead with the Supreme Judge, who is both Christ and God the Father, on man’s behalf.

At the same time it is characteristic of medieval iconography that we must not only look at the message of the whole. Every detail adds a subtle symbolic meaning. Hence there is so much more than can be seen at first sight. A white towel, for example, in the panel showing Mary refers to purity. The rose on the lawn stands for love, while the lily-of-the-valley symbolises innocence.

Focal points

Discover more on this topic

Vlaamse Primitieven in Brugge

Ludion, 2006.

Van Eyck: een optische revolutie

Hannibal, 2020.

De eeuw van Van Eyck 1430-1530: de Vlaamse Primitieven en het Zuiden

Ludion, 2002.

De Vlaamse primitieven: de meesterwerken

Mercatorfonds, 2002.

Het Lam Gods, Van Eyck: kunst, geschiedenis, wetenschap en religie

Hannibal, 2019.

Het Lam Gods

Davidsfonds, 2005.

Fiction

Dag Jan: het kleine rijk van Jan Van Eyck

Borgerhoff & Lamberigts, 2020. (10+)

Schilders & spionnen: het verhaal van de Vlaamse Primitieven

Davidsfonds/Infodok, 2008. (9+)

Margriete

De Geus, 2022.

Nu kijken

Bijkomend luister/kijk materiaal

Van Eyck: De verlokking van de werkelijkheid

(2020)