The arming of the craft guilds was nicely depicted in the medieval frescos of the chapel of the Leugemeete in Ghent, demolished in 1911 (drawings from the original) | Ghent, STAM, Bijlokecollectie

1302

Social Revolutions in the Towns of Flanders and Brabant

In the early morning of 18 May 1302 rebellious townspeople entered Bruges by stealth. They murdered the French garrison that was stationed there to keep unruly Flanders under control. The French king decided on a severe response, but on 11 July the French army of knights suffered a crushing defeat near Kortrijk against the militias of the Flemish towns. That unexpected victory continued to resound for a long period.

The Flemish count Guy of Dampierre had been at war with his liege lordlord who allowed his liegeman to use land in exchange for personal loyalty and military assistance. , the French king Philip the Fair since 1297. Philip sent an army to the county, placed it under his direct authority and imprisoned the count.

The rich merchants in the town councils of Bruges and Ghent took the side of the French king. But they were in conflict with the common people, organised in the craft guildsorganisations of people with the same occupation. . The latter therefore formed an alliance of convenience with the count’s party.

On 11 July 1302 it came to a pitched battle between the French troops and the supporters of the count: the so-called Battle of the Golden Spurs. The French underestimated the determination of organised foot soldiers against mounted knights. The victory of the common people made an impression all over Europe. A few years later the French successfully counter-attacked, but finally the French king failed to subdue the county of Flanders.

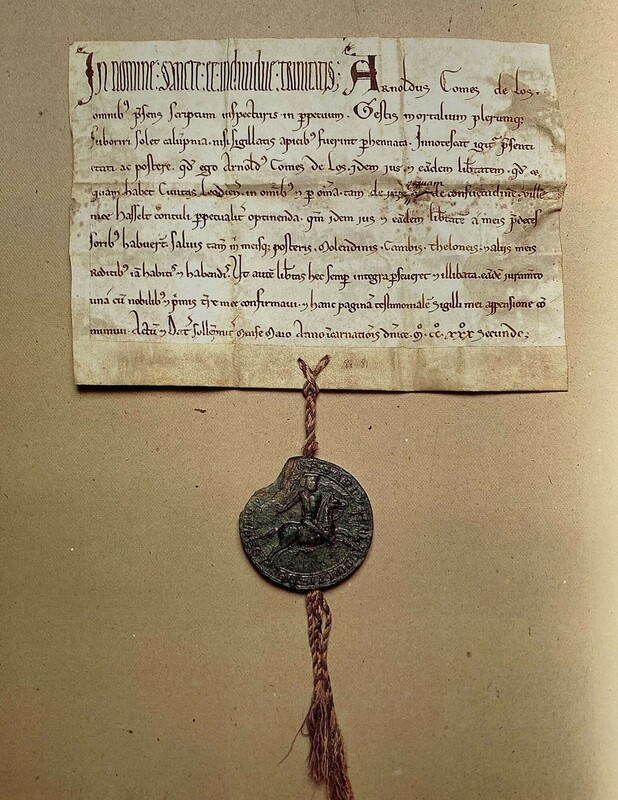

Leuven, Stadsarchief, Oud Archief 1296

Duke John II of Brabant (1275-1312) defeated the forces of the Brussels craft guilds at the Battle of the Vilvoordse Beemden (1306). In the statute of Kortenberg (1312) the duke sealed an agreement with the nobility and the urban elites in which he acknowledged the rights and freedoms of his subjects. In that sense this document was a distant precursor of what we today would call a constitution.

Social Revolutions in the Towns of Flanders and Brabant

The revolt of 18 May 1302 and the military encounter on 11 July 1302 were etched in the national memory by 19th-century Belgian writers and historians as national historic feats. In reality the events formed part of a feudalfeudal refers to the relationship between the liege lord, here the French king and the liegeman, here the count of Flanders. and social struggle that extended over a longer period.

The large-scale textile industry and trade in the towns of Flanders and Brabant made those towns sizeable, but also very turbulent. The population of the towns did not want to be governed according to noble whims, as still prevailed in the countryside. For that reason the towns regularly rebelled in order to assert their common interests. The frequency of such ‘democratic’ revolts was much higher in the Southern part of the Low Countries than elsewhere in medieval Europe.

In a first period of revolts the urban elites wanted to wrest rights and freedoms from the sovereign. For them political power was based on pacts between the ruler and his subjects. As a result you were entitled to resist an unjust ruler if he did not respect laws and customs.

In later revolts the common people, organised in the craft guilds, demanded its rights with respect to the urban elites. Common people also wanted their say and expected accountability from the town authorities. After 1302 the guilds of Bruges and Ghent obtained a far-reaching say in local government. A social revolution also took place in Mechelen, but the revolts in Brussels, Leuven and Diest failed.

Focal points

Discover more on this topic

Gouden tijden: rijkdom en status in de middeleeuwen in de Zuidelijke Nederlanden

Lannoo, 2016.

Eeuwen des onderscheids: een geschiedenis van middeleeuws Europa

Prometheus, 2020.

Brugge, een middeleeuwse metropool 850-1550

Sterck en De Vreese, 2020.

Noordzeehandel en middeleeuws Vlaanderen, ca. 1000-ca. 1300

Skribis, 2021.

Ieper en de middeleeuwse lakennijverheid in Vlaanderen

IAP, 1998.

‘Ghi Fransoyse sijt hier onteert: de Guldensporenslag [door] Lodewijk van Velthem

Davidsfonds, 2002.

Omtrent 1302

Universitaire Pers, 2002.

1302: feiten en mythen van de Guldensporenslag

Mercatorfonds, 2002.

Handelaren en ambachtslieden: een economische geschiedenis van de vroege middeleeuwen

Omniboek, 2021.

Geschiedenis van Brabant, van het hertogdom tot heden

Waanders, 2011.

1302: opstand in Vlaanderen

Lannoo, 2011.

Fictie

Om het land te beschermen

Averbode, 1987. (12+)

Val uit de tijd

Godijn Publishing, 2021.

Candide

Clavis, 2008. (13+)

Isabella’s geheim

De Leeskamer, 2010.

Floris en Belle

Luisterpunt, 2000. (13+)

Kroniek der Guldensporenslag

Talent, 2000. (16+) (vierdelige stripreeks)

Van Rompuy Hubert

De Sikkel, 1989. (10+)

De Leeuw van Vlaanderen

(1984)