The Bayard Steed and the four Heems children in Dendermonde in 2022 | Dendermonde, Ros Beiaardcomité vzw, Geert De Rycke

The Bayard Steed of Dendermonde

Processions and Parades

Every ten years a gigantic wooden horse trundles through the streets of Dendermonde: the Bayard Steed. On its back sit the four ‘Heemskinderen’, played by four brothers born in Dendermonde. Each time this parade attracts crowds of spectators.

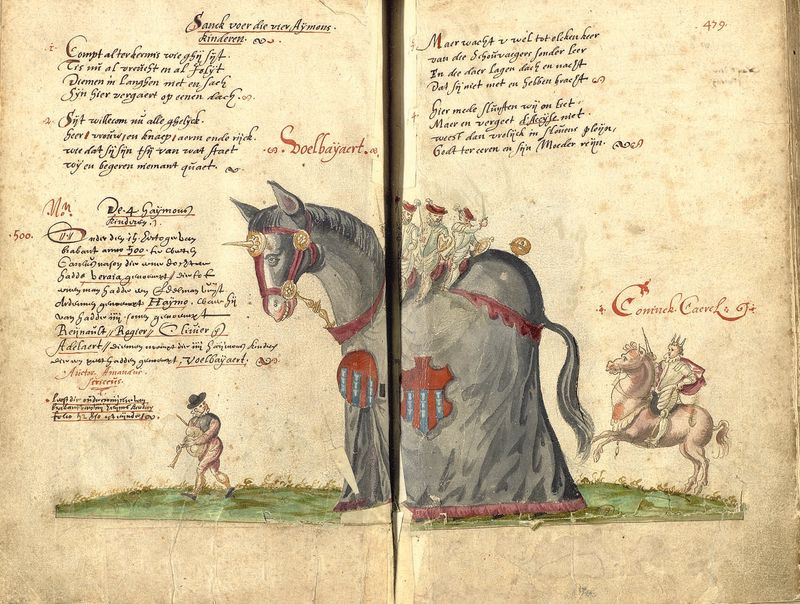

Since the 15th century the Bayard Steed has been an important presence in popular processions in a large number of towns. The horse comes from a medieval saga, which originated in France but spread all over Europe. In the Low Countries the story lived on as De historie van de vier Heemskinderen. According to the Dendermonde version of the story the horse was the stake in a life-and-death wager between Louis, the son of Charlemagne and the four sons of Aymon, the lord of Dendermonde. The brothers won the bet and killed their adversary. They fled on the horse, chased by the soldiers of Charlemagne. After a protracted conflict and under severe pressure the brothers surrendered their immensely strong horse at Charlemagne’s request. The death of Bayard settled the account and restored peace.

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, RP-P-2003-353

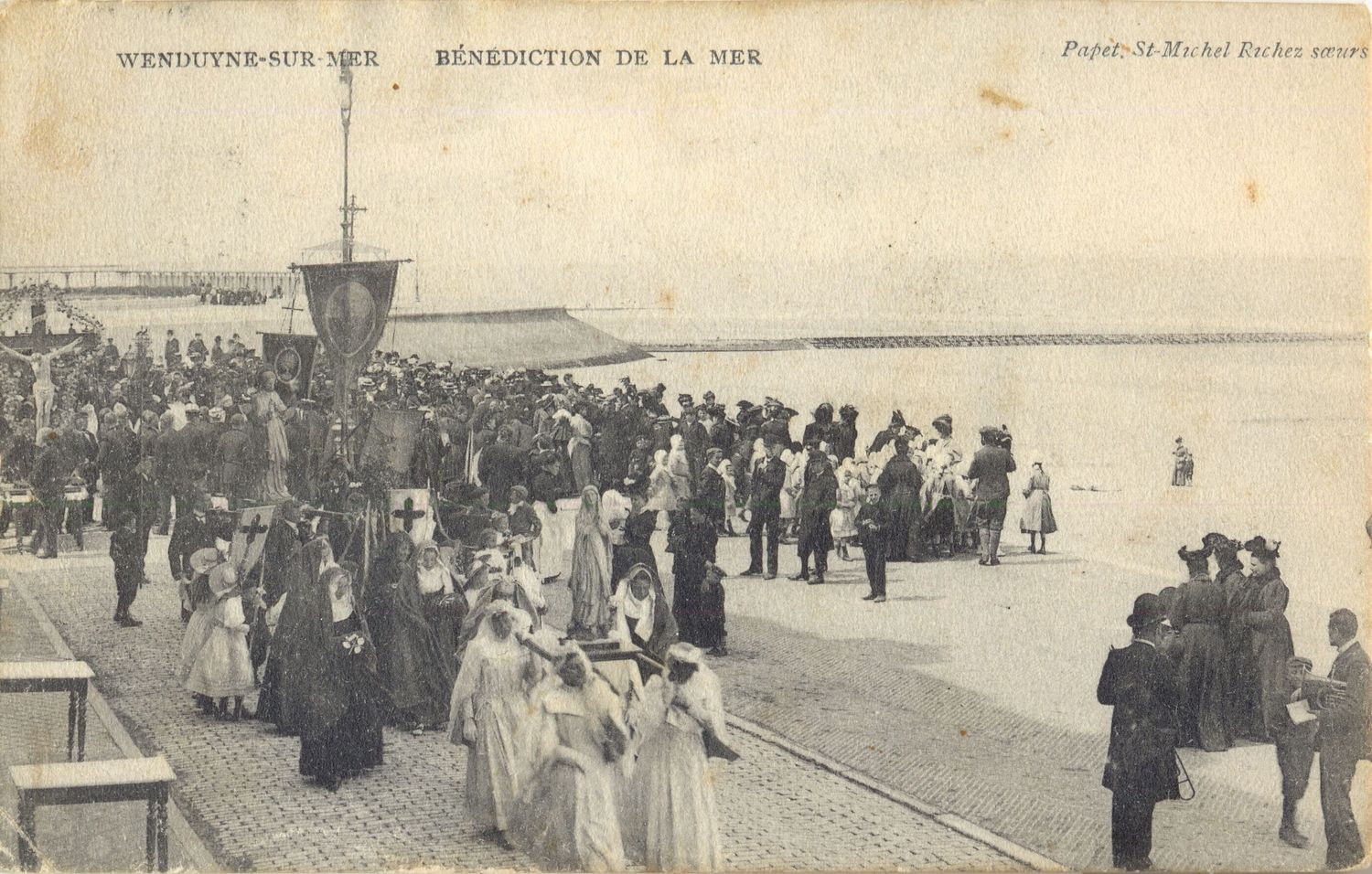

Fair and parade in a print by Pieter van der Borcht in the year 1553.

Processions and Parades

The origin of processions like the Bayard Steed lies in medieval processions and parades. Processions have a religious character. Often, they are rooted, like many religious holy days, in still older customs. Usually they honour a specific saint, whose likeness or relica remnant of the body of a saint or an object that has been in contact with a saint. is carried around. People worshipped relics to be restored to health or to avert a disaster.

Parades mostly derive from religious processions, which gradually acquired more worldly aspects. In that way figures and animals from sagas and legends, like the Bayard Steed, made their appearance. From the 16th century on processions appeared with an exclusively worldly theme. However, religious and worldly aspects often continued to interweave.

At the end of the 18th century the Austrian Emperor Joseph II restricted processions. Later the French authorities also banned worldly parades too. They regarded these practices as superstition.

In the 19th century there was a revival of both religious and worldly parades. The increasing interest in the Middle Ages played an important part. From the 1960s on a large number of processions again disappeared. The Catholic church attached less importance to popular devotionpopular religious practices and traditions. , and traditional popular culture also came under pressure. In some municipalities processions survived thanks to strong local traditions and their attractiveness for tourists and today they are appreciated as part of the country’s intellectual heritage.

Focal points

Discover more on this topic

Non-fiction

De historie vanden vier Heemskinderen

Bert Bakker, 2005.

Heiligen en tradities in Vlaanderen. Herfst en Winter

Davidsfonds, 2018.

Heiligen en tradities in Vlaanderen. Lente en Zomer

Davidsfonds, 2017.

Het zevende jaar. Processies in de regio Maas-Rijn

Peeters, 2010.

God in Vlaanderen: de kerken lopen leeg, maar de mensen vieren in velden en straten

Van Halewyck, 2011.

Voetsporen van devotie: processies in Vlaams-Brabant

Peeters, 2008.

Reuzen in Vlaanderen: volksleven van vijf eeuwen

Vlaams Boekenfonds, 1985.

Fiction

100 Brugsche legenden, sprookjes, sagen, anekdoten, spook- en heksenverhalen

Raaklijn, 1984.

De wolkeneters: 20 verhalen over reuzen

De Eenhoorn, 2021. (6+)

Suske en Wiske. Het ros Bazhaar (nr. 90)

Standaard Uitgeverij, 1974.

De vier heemskinderen

Van Goor, 1983.

Vlaamse Filmkens. De vier heemskinderen

Averbode, 1959. (10+)

Jommeke. Het verdwenen hoefijzer, (nr. 305)

Ballon Comics, 2021.

Sterke Jan: volksverhalen over reuzen, aardgeesten en legendarische helden

Elmar, 2002. (13+)

‘t Ros Beiaard doet zijn ronde: ommegangen, processies, gildefeesten

Traditionele muziek uit Vlaanderen (2001).