Simon Stevin, posthumous portrait | Leiden, Universiteitsbibliotheek, Douza-archief

Simon Stevin

A Scientific Lens

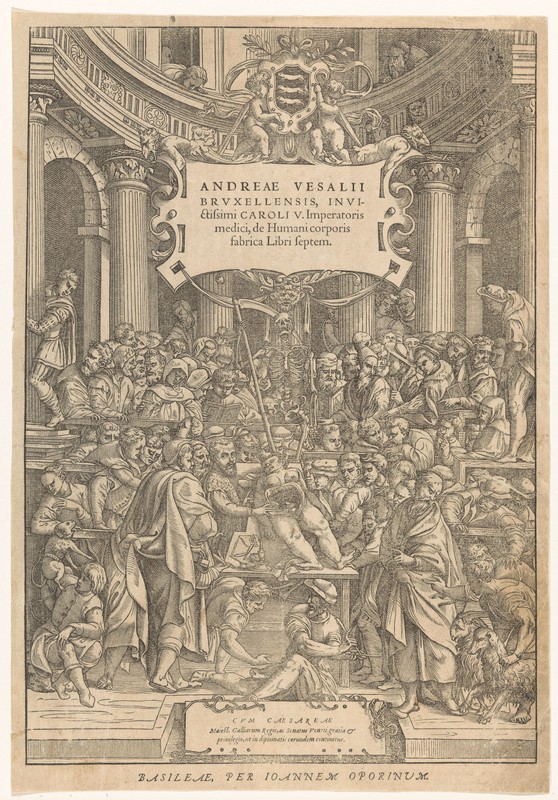

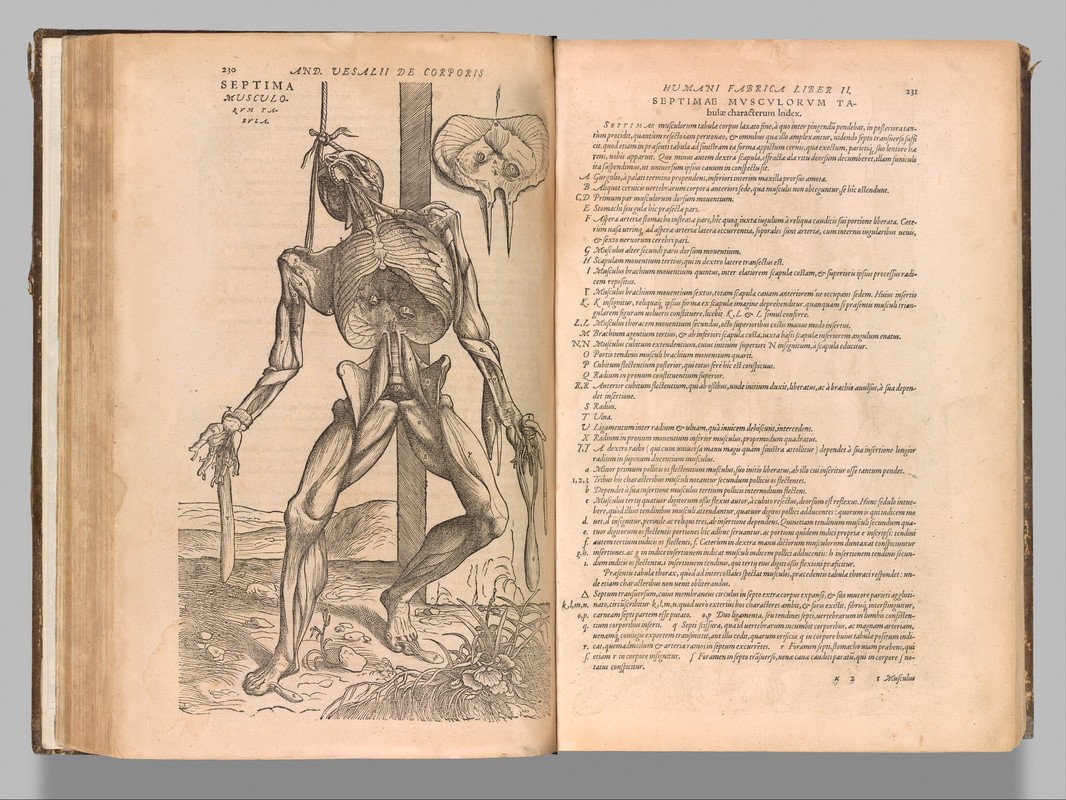

The versatile scientist Simon Stevin made important contributions to mathematics and physics, logic and language study, but as an engineer also found solutions for all kinds of practical problems. Together with, for example, Gerard Mercator and Andreas Vesalius, he embodied the modernisation of science.

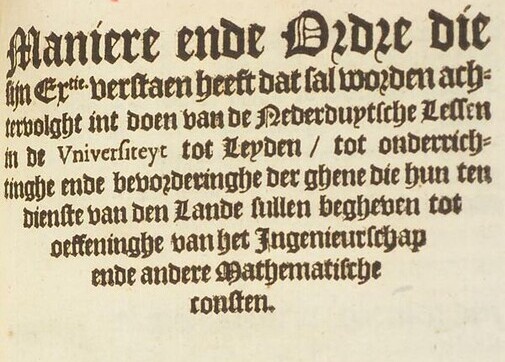

Stevin grew up in Bruges, worked for a while in Antwerp and in his thirties emigrated to Leiden, presumably because of his Protestant faith. He popularised the ten-part or decimal system, which had been devised as early as the 10th century in the Arab world, but which he developed further. He made up Dutch words which are still current, such as ‘evenwijdig’ (parallel), ‘wiskunde’ (mathematics) and ‘scheikunde’ (chemistry). In addition, he improved the operation of locks on waterways, he devised interest tables for the repayment of mortgages and laid the foundation for technical education. He was one of the first in the Low Countries to support Copernicus’ thesis that the earth revolves round the sun and believed in the principle of popular sovereigntythe principle that the highest authority lies with the people and a head of state must keep to laws and agreements with the population. . With his empirical and observation-based method of working he contributed to new, modern standards for science.

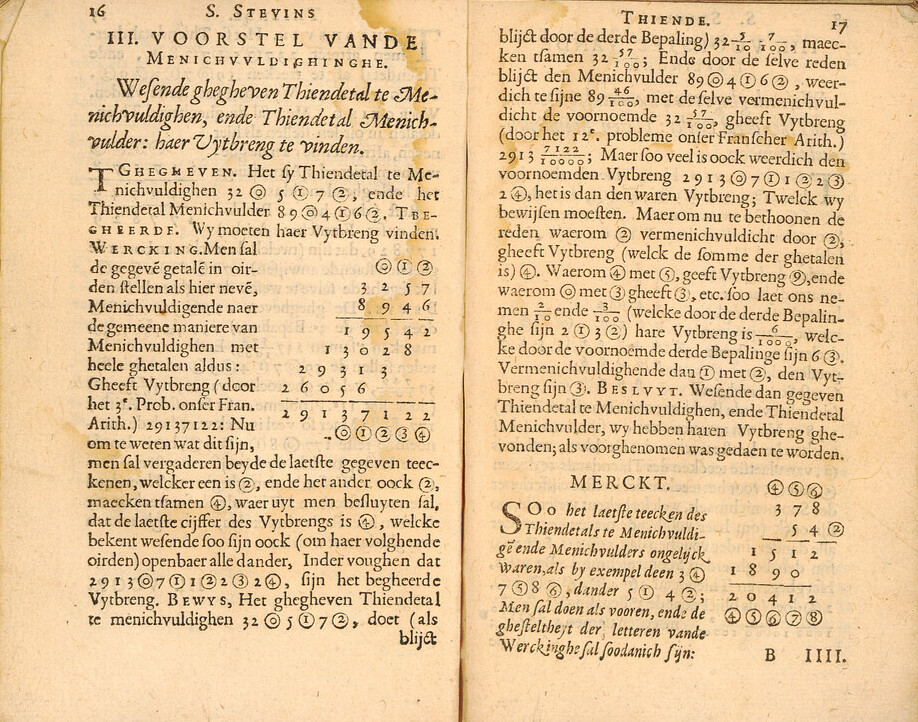

Antwerp, Collectie Stad Antwerpen, Hendrik Conscience Heritage Library, Flandrica, G 50187

In De Thiende (The Decimal, 1585) Stevin formulated the arithmetical rules for decimal numbers and discussed their practical applications. With his work Stevin put an end to the use in Europe of Roman numerals, with which it is difficult to calculate.

A Scientific Lens

In about 1586 Simon Stevin stood on the tower of the Nieuwe Kerk in Delft in order to drop two lead balls of different weight simultaneously. They hit the ground at the same time. With that simple experiment Stevin refuted Aristotle’s almost two thousand-year-old theory, which many scientists still followed. Light and heavy objects fall at the same speed! An experiment that in 2022 was repeated with extreme precision and confirmed.

Even more important than the outcome of this experiment was that Stevin demonstrated how theory in combination with experiments leads to a reliable scientific method. Not for nothing was his motto ‘Wonder en is gheen wonder’ (Wonder is no wonder): natural phenomena (wonderen) can be fathomed by science and so lose their inexplicable quality.

Like Andreas Vesalius. Rembert Dodoens and Gerard Mercator, Stevin was a face of the scientific revolution that took place in the 16th century. These scientists promoted new forms of research and devised scientific applications. They continued to draw inspiration from Classical antiquity, but no longer accepted old insights slavishly as true. They wanted to experiment for themselves, observe and formulate new laws.

Focal points

Discover more on this topic

Non-fiction

Vlaanderen in 100 kaarten

Davidsfonds, 2015.

Anatomia: de ontdekking van het menselijk lichaam in de Lage Landen (16de tot 18de eeuw)

Davidsfonds, 2017.

Mercator, de man die de wereld in kaart bracht

Ambo/Anthos, 2003.

Leuven en zijn colleges: trefpunt van intellectueel leven in de Nederlanden (1425-1797)

Sterck & De Vreese, 2021.

Wonder en is gheen wonder: de geniale wereld van Simon Stevin 1548-1620

Davidsfonds, 2003.

Simon Stevin, wetenschapper in oorlogstijd 1548-1620

Aspekt, 2007.

Wereldtheater. De geschiedenis van de cartografie

Athenaeum-Polak & Van Gennep, 2018.

Simon Stevin van Brugghe (1548-1620): hij veranderde de wereld

Sterck & De Vreese, 2020.

Wereldwijs: wetenschappers rond Keizer Karel

Davidsfonds, 2000.

Vesalius, het lichaam in beeld

Davidsfonds, 2014.

XVI. De zinderende 16de eeuw: Habsburgers, heksen, ketters & oproer in de Lage Landen

Borgerhoff & Lamberigts, 2021.

Fiction

Suske & Wiske. De mollige meivis (nr 93)

Standaard Uitgeverij, 1975.

Vesalius, een beroemd anatoom gevangen in de intriges van het Spaanse hof

Davidsfonds, 2014.

Andreas: de fictieve autobiografie van Vesalius, de grootste anatoom aller tijden

Van Halewyck, 2014.

Tussen god en de zee: roman over het leven en werk van Gerard Mercator

Kramat, 2004.