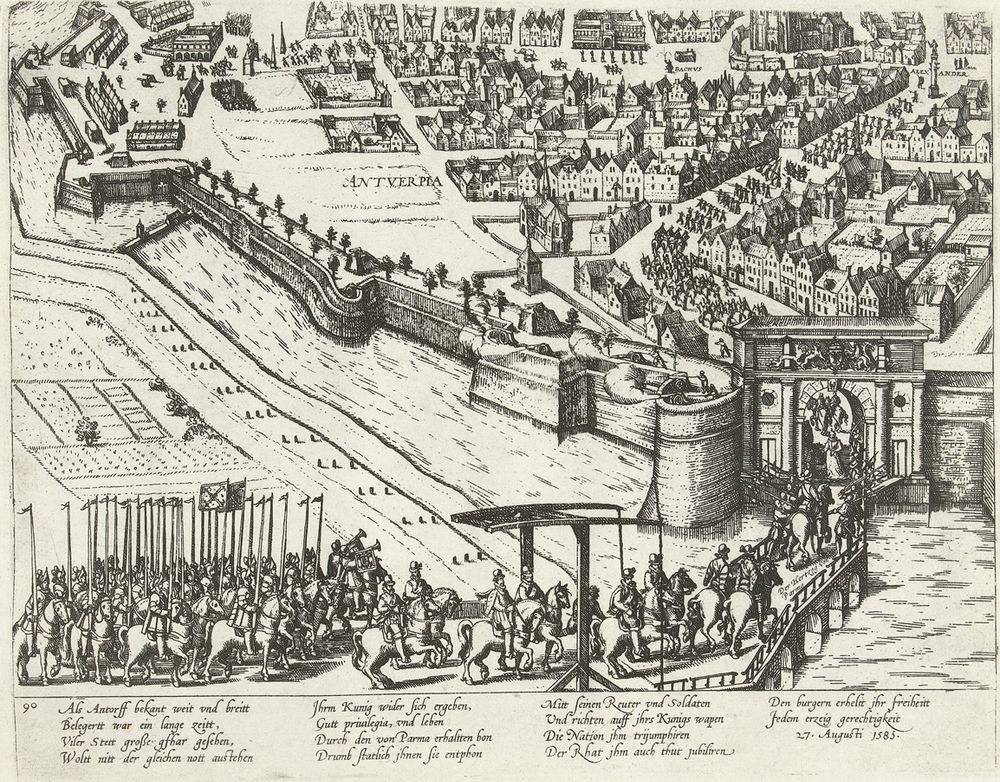

Statues are toppled from their plinths in a church during the Iconoclastic Fury. Etching by Frans Hogenberg, 1566-1570 | Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum. RP-P-OB-78.784-90

The Iconoclastic Fury

Civil War in the Low Countries

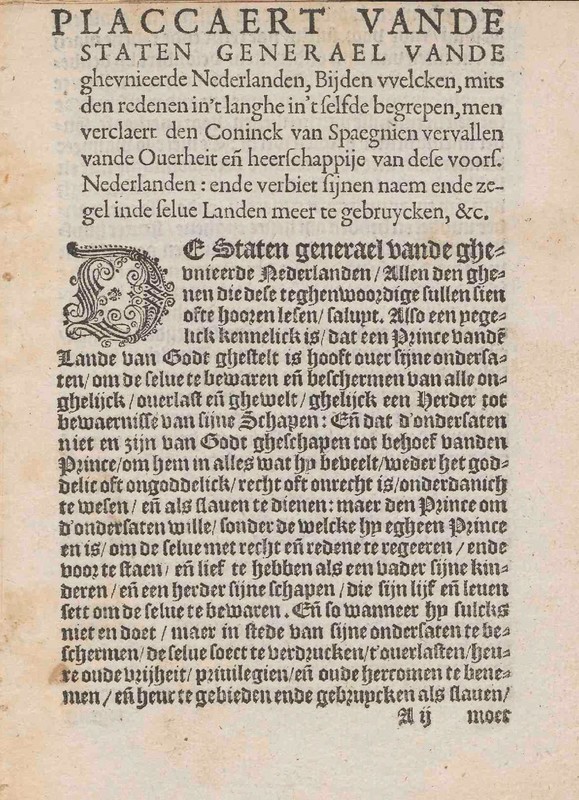

The divisions between Protestants and Catholics led to an iconoclastic fury, which in 1566 went through the Low Countries like a shockwave. Calvinists (Protestants) caused devastation in churches and monasteries. That was the beginning of the tumultuous events that led to the disintegration of the Low Countries.

On 10 August 1566 the hat maker Sebastiaan Matte gave a fiery field sermona clandestine address in the countryside. just outside Steenvoordeplace in the Westhoek, at present just across the French border. . Like so many Calvinist preachers, he attacked the worship of saints, but also the hypocrisy and greed of the Catholic church. His words found an eager audience among the many impoverished textile workers in the Westhoek.

When he had finished his listeners went to a nearby monastery and destroyed all the images of saints. From Steenvoorde that ‘Iconoclastic Fury’ raged through the Low Countries. On 20 August it was the turn of the Antwerp churches and monasteries. People from all levels of society participated. Generally, the destruction was well organised by local Calvinist associations and town councils did not intervene because they were well-disposed towards the new religion.

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-78.904

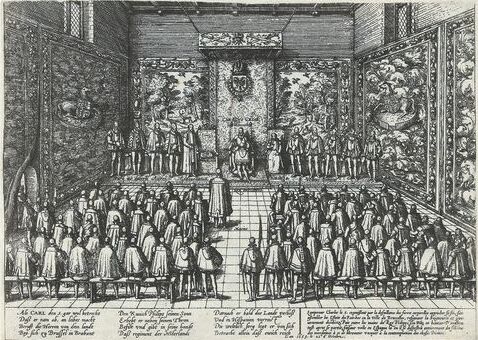

Nobles ask the regent for alleviation of the harsh anti-Protestant decrees (1566). They are mockingly called geuzen (beggars). Etching by anonymous artist, made between 1619 and 1649.

Civil War in the Low Countries

As early as the first half of the 16th century tensions had arisen in the Low Countries. The textile industry, so important in the countryside suffered serious competition from England. The Habsburg Emperor Charles V ordered the up-and-coming Protestantism to be persecuted. In 1555, when Charles’ son Philip II came to power, the situation became worse. Philip had been born and bred in Spain. His style of government and dependence on Spanish advisers did not go down well with the urban elite and the local nobility. New taxes caused discontent. Through his harsh treatment of Protestants Philip alienated even moderate Catholics.

Thus emerged the revolutionary atmosphere in which the Iconoclastic Fury could break out in 1566. The Spanish-Habsburg army was able to keep the lid temporarily on the rebellious mood, but in 1572 rebels were able to gain control of Holland and Zeeland. In 1576 the same thing happened in Flanders and Brabant. The nobleman William of Orange assumed leadership of the revolt. The rebels called themselves geuzen (beggars).

According to them Philip II, the lawful ruler, was a tyrant: he did not respect the rights and freedoms of his subjects. Because the king ignored their input, the geuzen rebelled. However, not all citizens shared that view, and so the revolt turned into a civil war. People from the same town, the same area found themselves in opposite camps.

Focal points

Discover more on this topic

Non-fiction

1585: de val van Antwerpen en de uittocht van Vlamingen en Brabanders

Lannoo, 2010.

Oranje tegen Spanje (1500-1648)

Davidsfonds, 2022.

De Tachtigjarige Oorlog: opstand en consolidatie in de Nederlanden (ca. 1560-1650)

Walburg Pers, 2022.

De Beeldenstorm: van oproer tot opstand in de Nederlanden

Walburg, 2015.

De Reformatie: breuk in de Europese geschiedenis en cultuur

Walburg Pers, 2017.

Antwerpen in de tijd van de Reformatie: ondergronds protestantisme in een handelsmetropool, 1550-1577

Kritak, 1996.

In Opstand! Geuzen in de Lage Landen

Horizon, 2022.

De Opstand 1568-1648: de strijd in de Zuidelijke en Noordelijke Nederlanden

Uitgeverij Omniboek, 2018.

De geuren van de kathedraal. De overweldigende 16de eeuw in Antwerpen

Lannoo, 2023.

XVI. De zinderende 16de eeuw: Habsburgers, heksen, ketters & oproer in de Lage Landen

Borgerhoff & Lamberigts, 2021.

Fiction

Gebroken

Manteau Thriller, 2012.

Het geuzenboek

De Arbeiderspers, 2019.

Ketters van de Kemmelberg

Scriptomanen, 2017.

Papinette

Clavis, 2015. (15+)

Isabella’s geheim: historisch mysterie

De Leeskamer, 2010.

Vreemdeling

Clavis, 2021. (13+)

De Torens van Schemerwoude. De Dulle Griet.

Ballonkids (nr. 13), 2006. (stripverhaal)

Tanne en ik

Luisterpunt, 2014. (15+)

Wildevrouw

De Bezige Bij, 2021.

De verloren droom van Pieter Gillis: historische roman over Antwerpen tussen Reformatie en humanisme

Davidsfonds, 2010.

Tijl Uilenspiegel

Vrijdag, 2022.

Suske en Wiske: De Laaiende Linies (nr. 319)

Standaard, 2022.

Galgenmeid

Davidsfonds Infodok, 2010 (14+).

Suske en Wiske. Het Spaanse spook (nr. 10)

De Standaard, 1971.