Herdenkingsring voor Cathelyne Van den Bulcke op de Grote Markt van Lier | Chris Van Rompaey.

Cathelyne Van den Bulcke

Witch Trials in Europe

On 20 January 1590 Cathelyne Van den Bulcke was burnt at the stake in the market-place of Lier. She was one of the many ‘witches’ who between the 15th and 18th century were victims of popular superstition. In 2021 she was formally rehabilitated by the town of Lier. In so doing Lier was following in the footsteps of Nieuwpoort, Diksmuide and many other European towns.

Cathelyne Van den Bulcke had been accused of witchcraft by a thirteen-year-old girl, Anneken Faes. She had also been accused of sorcery. During her torture the girl maintained that Cathelyne Van den Bulcke had seduced her into contact with the devil. The gossip that circulated in Nijlen, where she lived, did her case no good. Moreover, her mother had also been executed as a witch. During the trial, which took place in Lier, her fellow-villagers testified for and against her. She herself denied everything. Then the panel of aldermen ordered her to be tortured, after which Van den Bulcke ‘confessed’, but accused no other women.

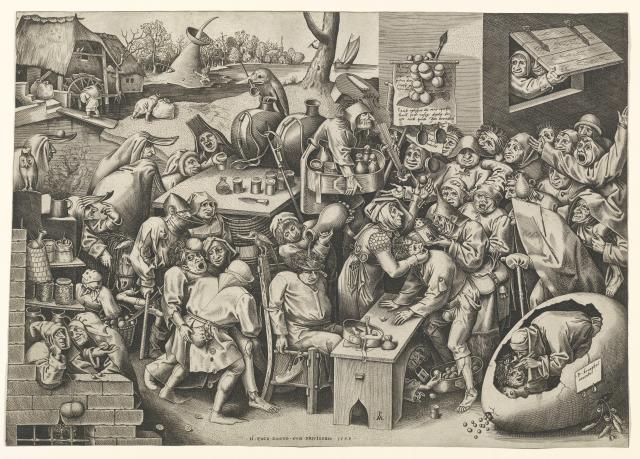

Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, fr. 12476, fol. 105v

One of the oldest representations of a witch, from 1451. From Le Champion des dames by the French poet Martin le Franc.

Witch Trials in Europe

Many witch trials took place in the southern part of the Low Countries between the 15th and 18th century. How many people were tortured and executed, we do not know exactly, since many archives have been lost. It does, however, emerge from the trial documents that witches often received a ‘mild’ sentence, such as banishment. Others were released – often cases did not come to trial. Still, in the county of Flanders between 1450 and 1680 at least two hundred ‘witches’ died at the stake. As far as is known, Martha van Wetteren was the last of these. She was burnt at the stake in Belsele in 1684. In Leuven, in the duchy of Brabant, it went on still longer. There, two further executions took place in 1692 and 1695.

Witch trials were found all over Europe, but not everywhere in equal numbers. Present-day Germany had the most executions. In Poland and Russia too there was much persecution, in the Dutch Republic, Spain, Portugal and the Italian city states much less. Within the southern part of the Low Countries the differences were great. Most sorcery trials took place outside the large towns, in areas where there was little control of the courts, as in the south of what is today West-Flanders. In Nieuwpoort, for example, in the first half of the 17th century, 31 witch trials took place.

Focal points

Discover more on this topic

Non-fiction

De heksen en de buren. Heksenprocessen in de Lage Landen, 1598-1652

Davidsfonds, 2015.

Met de duivel naar bed. Heksen in de Lage Landen

Van Halewyck, 2002.

Het gevecht met de duivel. Heksen in Vlaanderen

Davidsfonds, 1999.

Fiction

Nelle, de heks van Cruysem

Manteau, 2011. (12+)

Aude

Clavis, 2005. (12+)

Heksenjong

Clavis, 2017. (12+)

Het duivelskind

Davidsfonds, 1991. (13+)

De Rode Ridder. De Vloek van Malfrat

Manteau, 2013. (9+)

De heks van Limbricht

Lebowski Publishers, 2021.

Suske en Wiske: Jeanne Panne (nr. 264)

Standaard Uitgeverij, 2000.

De heks van Axel

Davidsfonds, 2003. (12+)

De amulet

Lemniscaat, 2010. (12+)

Heksen moeten branden: de heks van Nattenhaasdonk

Abimo, 2013. (12+)