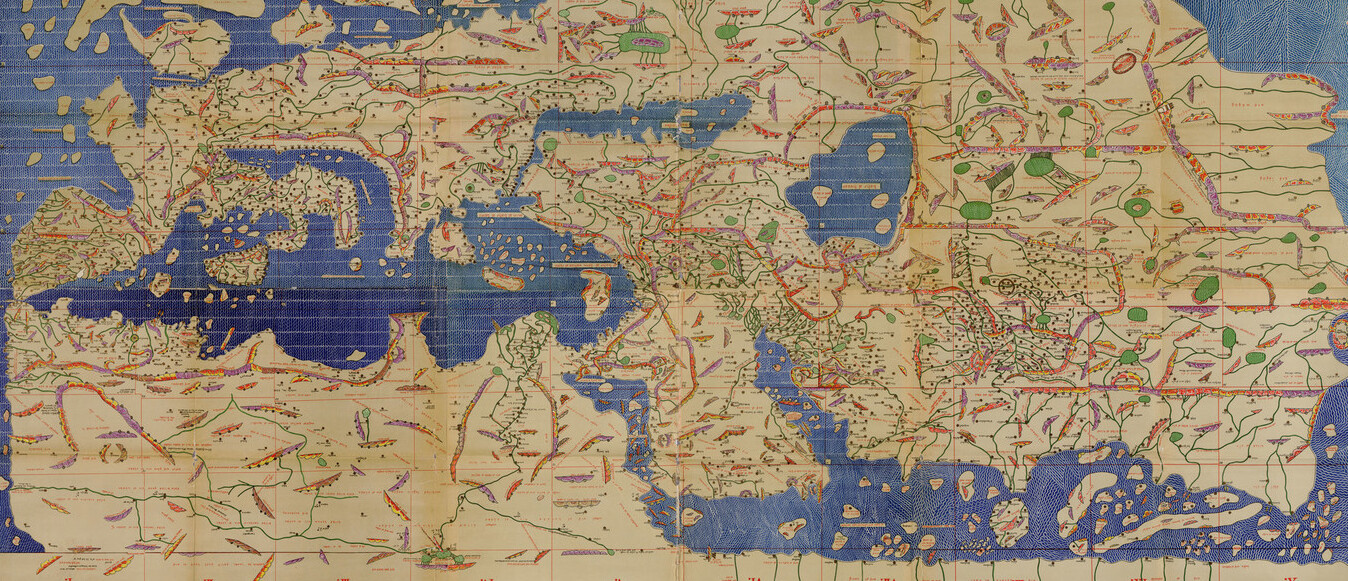

A detail of the world map from the ‘Kitāb Roedjar’ | Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Wikimedia Commons

Towns on the Map of Al-Idrisi

Contacts with the Muslim World

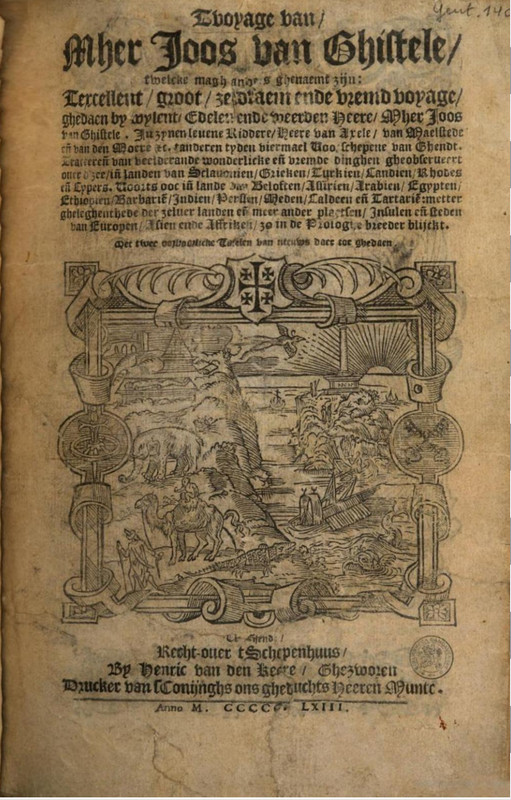

‘Kent’ (Ghent), ‘Abrugs’ (Bruges), ‘Sant Mir’ (Saint-Omer)… Under those corrupt names various Flemish towns appeared on a map of the 12th century. Muhammad Al-Idrisi achieved a considerable feat. In an age of limited information he managed to map the world he knew.

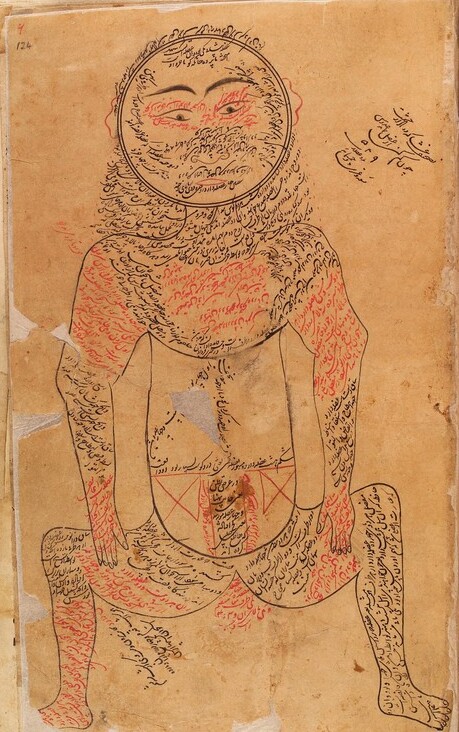

Al-Idrisi was a scholar from a distinguished Maghreb family. In around 1154, having been commissioned by the (Christian) king of Sicily Roger II, he completed the Kitāb Roedjar or ‘Book of Roger’, a description of the world as he knew it. For Al-Idrisi Sicily was the ideal spot to learn more about regions where he had never been. Much knowledge was gathered on that island, which was a crucible of Christians, Muslims and Jews and where numerous traders and travellers visited in passing. Probably Al-Idrisi sought information from them about towns in the Low Countries that he thought important enough to mention on his map. His description was not always accurate, because he was basing himself on incorrect statements. That was not exceptional: Western scholars also used dubious sources when they wrote about distant lands.

Wikimedia Commons

A complete, modern version of Al-Idrisi’s world map. He positioned the south at the top and saw the Middle East as the centre of the world. The Low Countries are at bottom right.

Contacts with the Muslim World

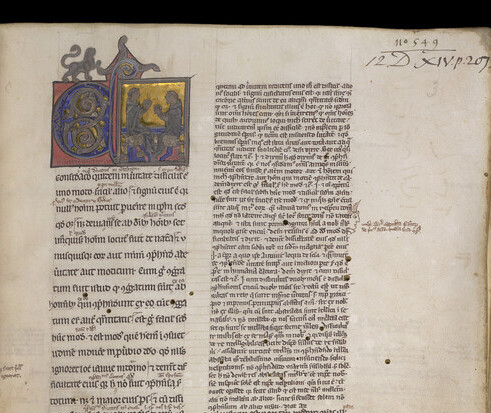

At the beginning of the Middle Ages Western Europe was not a very fruitful area for science and culture. After the fall of the Western Roman Empire (in 476) the region found itself in crisis. Much of the knowledge that had been built up in antiquity was forgotten. Only the great abbeys kept a number of Greek and Latin works in their libraries. Under Charlemagne (about 800) intellectual life again flourished. But Western Europe lagged behind the Muslim world, which extended from Southern Europe deep into Central Asia. Certainly, in the Al-Andalus region, the south of present-day Spain, scientists and philosophers went to work with knowledge from antiquity. Islamic and Jewish scholars initiated new developments in medicine and philosophy.

From the 12th century on, partly thanks to the Islamic world, culture and science gained a second wind in Western Europe. Christian scholars were influenced by writings from Al-Andalus. Mathematical terms such as ‘algebra’ and ‘algorithm’ come from Arabic. In addition, the Europeans rediscovered part of the legacy of Classical antiquity via scholars from the Islamic world. In this way knowledge was passed from one civilisation to another, each time with additions and new insights.

Focal points

Discover more on this topic

Wereldgeschiedenis van Vlaanderen

Pelckmans, 2018.

De bibliotheek van Bagdad: de bloei van de Arabische wetenschap en de wedergeboorte van de westerse beschaving

Boekerij, 2012.

De zijderoutes. Een nieuwe wereldgeschiedenis

Spectrum, 2017.

Het Huis der Wijsheid: hoe Arabieren de westerse beschaving hebben beïnvloed

Uitgeverij Bulaaq, 2010.

‘Rovers, christenhonden, vrouwenschenners’: de kruistochten in Arabische kronieken

Muntinga, 2001.

In de ban van Mohammed. Nicolaes Cleynaerts’ brieven uit de Arabische wereld.

Sterck & De Vreese, 2021.

Vier brieven over het gezantschap naar Turkije

Verloren, 1994.

De Belgische ontdekkingsreizigers

Lannoo, 2016.

Fiction

Busbeke of de thuiskomst

Davidsfonds, 2000.

Rubroeks reizen

Davidsfonds, 2009.

Nicolas Cleynaerts. Christenhond tussen moslims

Davidsfonds Uitgeverij, 2018

De odyssee van Pedro en Luisão

Davidsfonds Uitgeverij, 2019.

Het hermetisch zwart

Athenaeum, 1968.