In the early 17th century the old loam houses of the Diest béguinage were replaced with stone houses. The béguinage in 2021 | Evelien Impens

Béguinages

Women Join Forces

Today béguinages (begijnhoven) are oases of calm in many towns. The oldest date back to the 13th century. From the late 12th century on groups of unmarried religious women, called béguines, started to live together in towns. First in a collective dwelling called a convent, later also in houses around a courtyard. Convents were found everywhere in Western Europe, béguinages mainly in the Low Countries.

Up to now some thirty béguinages have been preserved. Most are still recognisable in the urban tissue, since they have kept their walls and medieval ground plan. The preserved houses date mainly from the 17th century. You no longer find béguines in them today. The last Flemish béguine lived in the béguinage of Kortrijk until 2005. Béguinages now have a social function, housing museums and other cultural institutions and offer residents and visitors a quiet space in town. In 1998 UNESCO recognised the béguinages of Bruges, Dendermonde, Diest, Ghent, Ghent Sint-Amandsberg, Hoogstraten, Kortrijk, Leuven, Lier, Mechelen, Sint-Truiden, Tongeren and Turnhout as world heritage sites.

Stad Kortrijk

Superintendent Augusta Seurynck (1895-1979) was in charge for a while of the béguinage in Kortrijk, 1974.

Women Join Forces

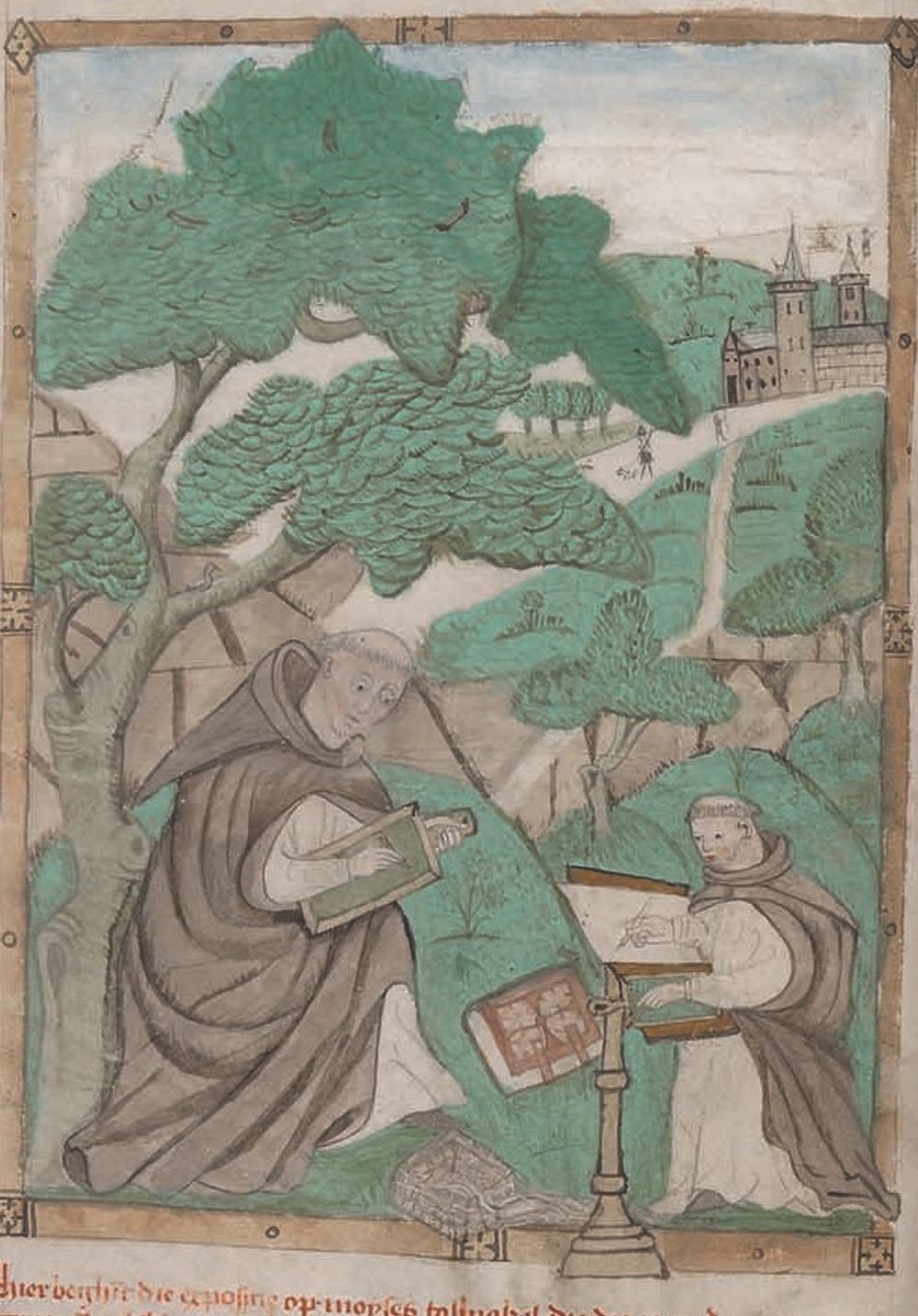

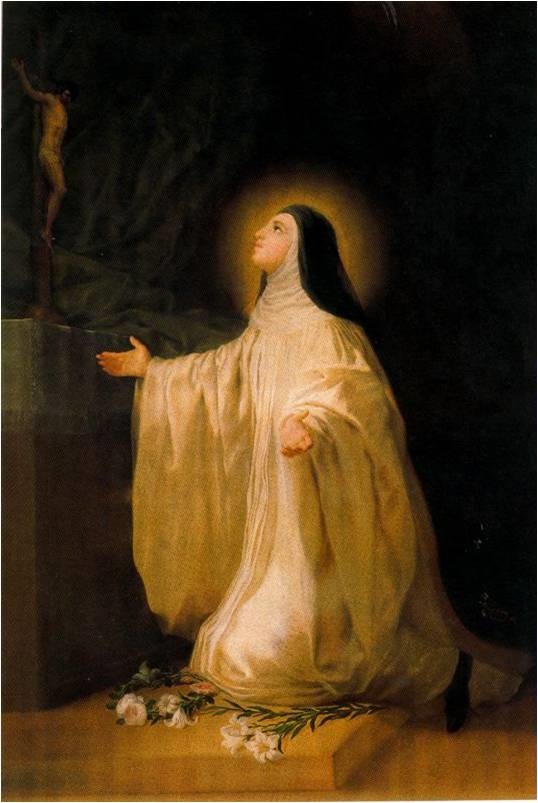

In the late Middle Ages many people looked for new ways of professing their faith. From the end of the 12th century unmarried women and widows settled near a church or monastery to work and pray together. They followed the example of a few well-known, charismatic women, who tried to live simply and piously, ‘in imitation of Christ’. The key figures in the movement were often rich, cultured women, but there were also poorer béguines. They earned their living through manual labour, in the textile sector or as washerwomen. Béguines also worked in hospitals and orphanages.

A thriving economy led to the growth of the European urban centres. More and more people, including many unmarried women, moved into the towns. In the béguinages single women found a safe, attractive and socially accepted workplace, without losing their economic independence completely. Béguines were not nuns. They did not take vows of poverty, though they did pledge chastitysexual abstinence. and pietyreligious faith. . They kept their possessions and could leave the béguinage, for example to get married.

A béguinage was managed by mistresses, elected by the béguines. But the priest, the bishop and the town authorities deliberately limited the freedom of the béguines, out of distrust of these communities.

Focal points

Discover more on this topic

Non-fiction

Een onafhankelijke vrouwenwereld . Van de 12de eeuw tot heden. De Vlaamse begijnhoven

The Hervé Caloen Foundation, 2003.

Gelovige en verstandige vrouwen maken geschiedenis: over begijnen en begijnhoven in context

Halewijn, 2018.

Begijnhoven, eeuwenoud, eigentijds

Feathers On Wings, 2018.

Stad van vrouwen. Over begijnen en begijnhoven

Davidsfonds, 2016.

Vlaamse begijnhoven ontdekken en beleven

Delta, 2000.

Begijnhoven in Vlaanderen

Openbaar kunstbezit, 2001.

Het besloten hof: begijnen in de Zuidelijke Nederlanden

Van Halewyck, 1998.

Vlaamse Begijnhoven. Werelderfgoed

Leuven, Davidsfonds, 2001.

Stemmen op schrift. Geschiedenis van de Nederlandse literatuur vanaf het begin tot 1300

Bert Bakker, 2006.

Hooglied. De beeldwereld van religieuze vrouwen in de Zuidelijke Nederlanden, vanaf de 13de eeuw

Snoeck-Ducaju & Zoon, 1994.

De besloten hofjes van Mechelen: laatmiddeleeuwse paradijstuinen ontrafeld

Hannibal, 2018.

Fiction

De vrouwen van het hof

Davidsfonds, 1994.

De nacht van de begijnen

Ambo-Anthos, 2018.

Jommeke. Alarm in’t Begijnhof (nr. 190)

Ballon Media, 1996.

Jommeke. De ooievaar van Begonia (nr. 8)

Het Volk, 1961.

De zeer schone uren van Juffrouw Symforosa, begijntjen

1918.

Toevluchtsoord

Manteau, 2007.

Spreeuwenjong

Manteau, 2008.

Verzegeld

Manteau 2009.