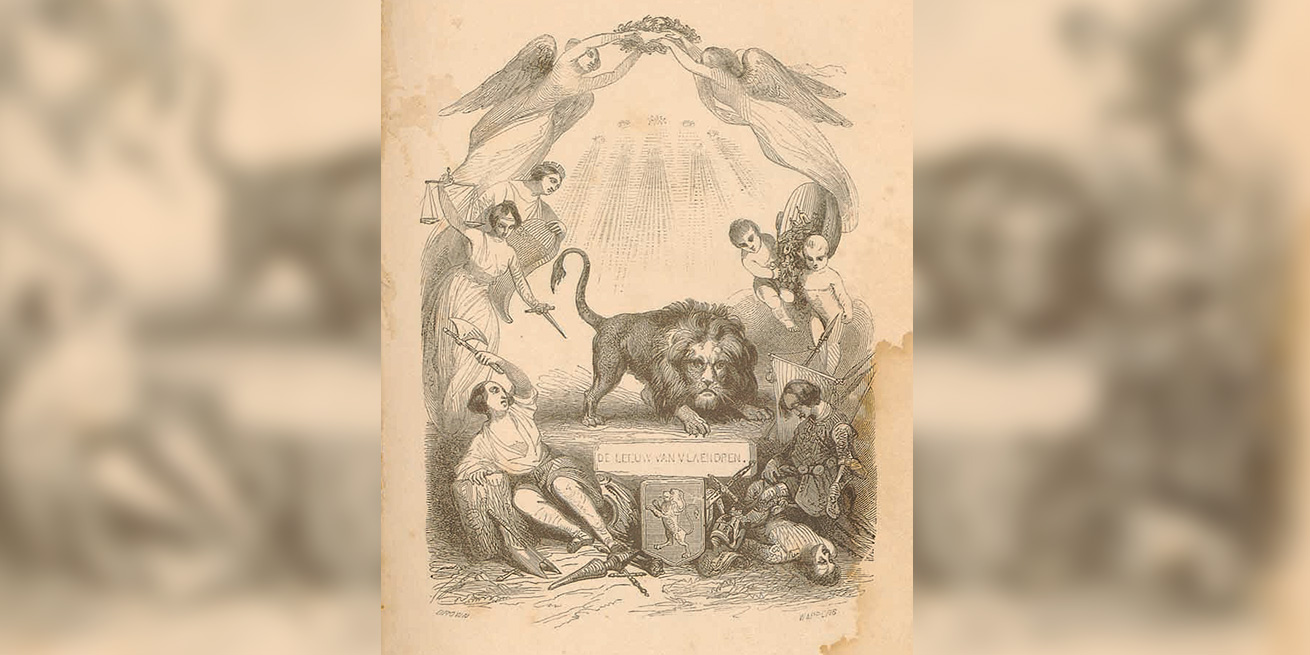

Frontispiece of De Leeuw van Vlaenderen, of de Slag der Gulden Sporen (The Lion of Flanders, or the Battle of the Golden Spurs, 1838). Designed by Gustaaf Wappers (1803-1874) | Antwerp, Collectie Stad Antwerpen. Letterenhuis

The Lion of Flanders

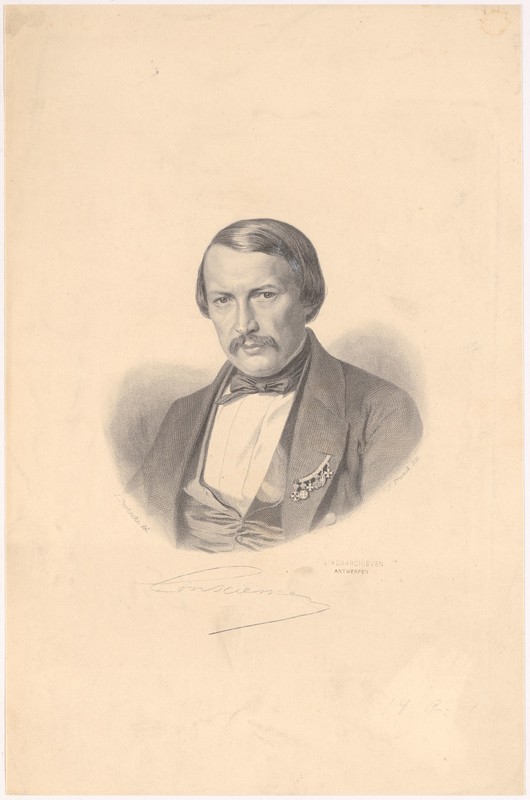

Hendrik Conscience and the Flemish Movement

Why does the Flemish Community celebrate on 11 July, why does the Flemish anthem honour a proud lion and why does the same animal decorate the Flemish flag? It all dates back to the success of one book: De Leeuw van Vlaenderen (the Lion of Flanders) by Hendrik Conscience.

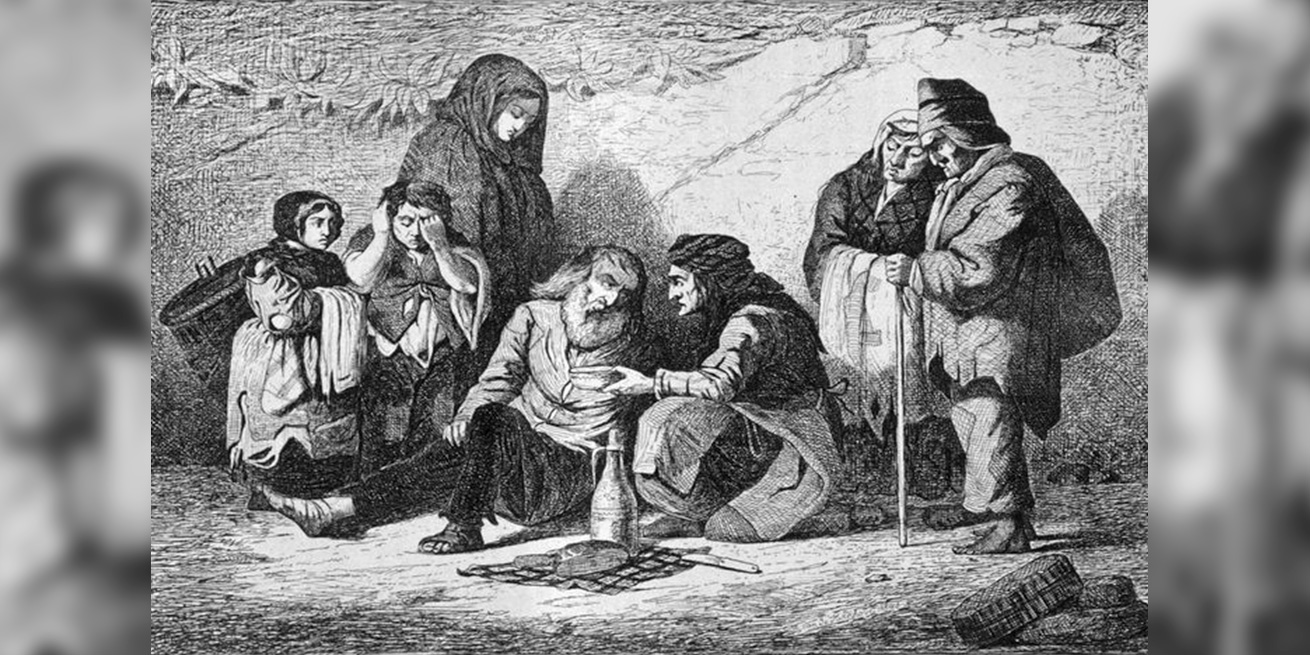

In 1838, from old chronicles and a good dose of fantasy Conscience concocted a novel about the tensions between France and the county of Flanders in the early 14th century. We make the acquaintance of Guy of Dampierre, the wise count, and his son Robert of Béthune, whose nickname is the ‘Lion of Flanders’. Equally unforgettable are Pieter de Coninck and Jan Breydel whom Conscience places at the head of the Bruges craft guilds. On 11 July 1302, side by side with the Lion of Flanders, these popular leaders defeat the French army. Thanks to the novel the bloody battle near Kortrijk is known as the Battle of the Golden Spurs.

Conscience regularly took liberties with the historical facts. He wanted not only to entertain his readers but also to impart a Flemish self-awareness. His aim succeeded: De Leeuw van Vlaenderen conquered many readers’ hearts and laid the basis for Flemish national symbolism.

Wikimedia Commons

Hendrik Conscience was honoured during his lifetime with a statue by Frans Joris (1851-1914) in the Antwerp square that was named after him. He died shortly after the inauguration in 1883.

Hendrik Conscience and the Flemish Movement

Hendrik Conscience, born in Antwerp, began his writing career in French. That was fairly logical: his father was an émigré Frenchman and in the newly-created Belgium French seemed destined to become the only official language. Nevertheless, Conscience switched to his mother’s language, Dutch, at the time called Nederduits or Vlaams. He had become convinced that his own mother tongue and that of the majority of Belgians deserved an official status and a literature of its own.

Other authors followed in the footsteps of Conscience. In this way in the 19th century literature was the engine of the Flemish movement. That movement appealed in the first instance to bilingual intellectuals from the lower bourgeoisie. It fought for the recognition of the Dutch language in public life and promoted a Flemish cultural identity. A great contribution to this Flemish cultural awareness was made by the liberal Willemsfonds (named after Jan Frans Willems) and the Catholic Davidsfonds (named after the Leuven professor and priest Jan-Baptist David). These organisations published books, founded libraries, encouraged language study and stimulated Flemish music and theatre.

Flamingants focused on language and culture, but were not blind to the great poverty and poor working conditions in Flanders. Like Liberals and Catholics, however, they proposed solutions that went no further than charity. The causes of social inequality, partly under the influence of the rise of socialism, found their way only later onto the political agenda.

Focal points

Discover more on this topic

Non-fiction

Het slechte geweten van Vlaanderen. Nationalisme, racisme en kolonialisme in de tijd van Hendrik Conscience

Davidsfonds Uitgeverij, 2022.

Davidsfonds. 1875-2000

Davidsfonds, 2000.

De Belgische natie viert: de Belgische nationale feesten, 1830-1914

Universitaire Pers Leuven, 2001.

De grote mythen uit de geschiedenis van België, Vlaanderen en Wallonië

EPO, 1996.

Onvoltooid Vlaanderen. Van taalstrijd tot natievorming

Uitgeverij Vrijdag, 2017.

Voor moedertaal en vaderland. Hendrik Conscience biografie

Vrijdag, 2021.

Albrecht Rodenbach: biografie

Lannoo, 2002.

Alles is taal geworden. Geschiedenis van de Nederlandse literatuur 1800-1900

Bert Bakker, 2016.

Vlaamsch van taal, van kunst en zin. 150 jaar Willemsfonds

Willemsfonds en Liberaal Archief, 2001.

De verbeelding van de leeuw. Een geschiedenis van media en natievorming in Vlaanderen

Peristyle, 2020.

Van de Belgische naar de Vlaamse natie: een geschiedenis van de Vlaamse beweging

Acco, 2010.

Fiction

De Rode Ridder – De Leeuw van Vlaanderen

Standaard Uitgeverij, 1984. (stripverhaal)

Hendrik Conscience, De Leeuw van Vlaenderen of de Slag der Gulden Sporen

Lannoo, 2002.

Een puit met hete pootjes: gedichten van Guido Gezelle voor kinderen van alle leeftijden

Bakermat, 1993. (9+)

Nu kijken

Bijkomend kijk/luister materiaal

De Leeuw van Vlaanderen

(1984)