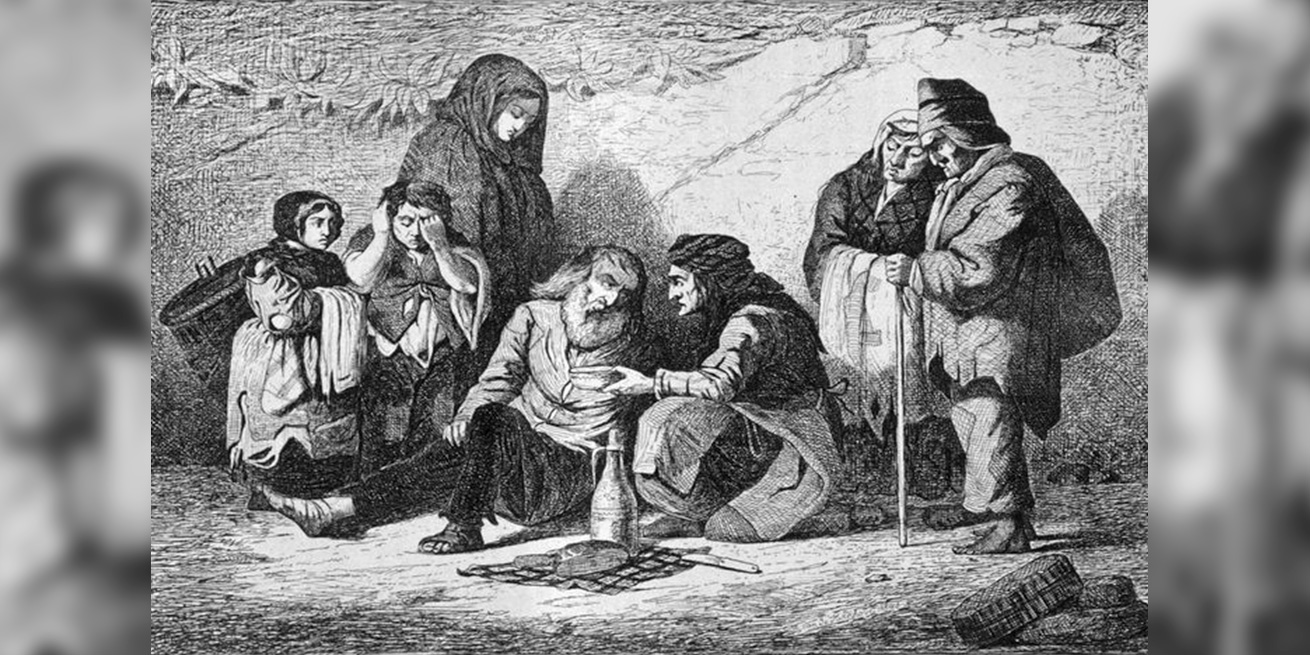

De ets Misère des Flandres (1848) getuigt van de toenmalige armoede in Oost- en West-Vlaanderen | Leuven, Centrum Agrarische Geschiedenis, B00001861

The Potato Crisis

‘Poor Flanders’

Between 1845 and 1847 a hitherto unknown fungal disease destroyed the potato crop in large parts of North-West Europe. This resulted in the last great European famine in peacetime. The provinces of East- and West-Flanders were also badly hit.

The potato blight was first noticed in Belgium in the area around Kortrijk in the summer of 1845. A fungus had spread through North-West Europe in no time at all and in many places played havoc with the potato crops. Ireland suffered exceptionally badly. To make matters worse the rye and wheat harvest also failed in 1846.

In Belgium the potato blight was worst in East- and West-Flanders. Precisely that region had suffered badly from the decline of the traditional linen industry. The results were dramatic. An estimated 44,000 people died from hunger and disease in Belgium between 1845 and 1847, some 30,000 of them in the two provinces.

Kortrijk, Texture Museum of Flax and Textiles

In the first half of the 19th century tens of thousands of families had a simple loom at home. They supplemented their limited income from agriculture by weaving linen materials.

While Liège and Hainaut grew into industrial regions in the 19th century, East- and West-Flanders remained rural areas with a great deal of cottage industry. Many small farmers in that region supplemented their agricultural earnings with income from the flax or linen industry.

The linen industry was a craft activity at this time. Production took place not in large factories, but spread throughout thousands of country dwellings. Flax farmers worked the flax into flax fibres. Spinners spun them into flax yarn. Weavers wove the yarn into linen cloths to the specifications of a merchant-entrepreneur. And all this at lower and lower piece rates.

Linen was an important but vulnerable export product. In around 1830 the British had perfected the mechanical spinning of flax thread, allowing them to produce massive amounts of flax yarn cheaply. The competition was fatal for the craft flax thread of Flemish homeworkers. The almost 220,000 spinners who were still active in cottage industry, became impoverished overnight.

The situation was made worse in the second half of the 1840s by the potato crisis. Hunger, poverty and diseases like typhus and cholera caused much misery in rural Flanders. A large part of cottage industry went under. The extensive poverty in the Flemish countryside lasted for decades and the expression ‘Poor Flanders’ would affect its self-image for a long time to come.

Focal points

Discover more on this topic

Non-fiction

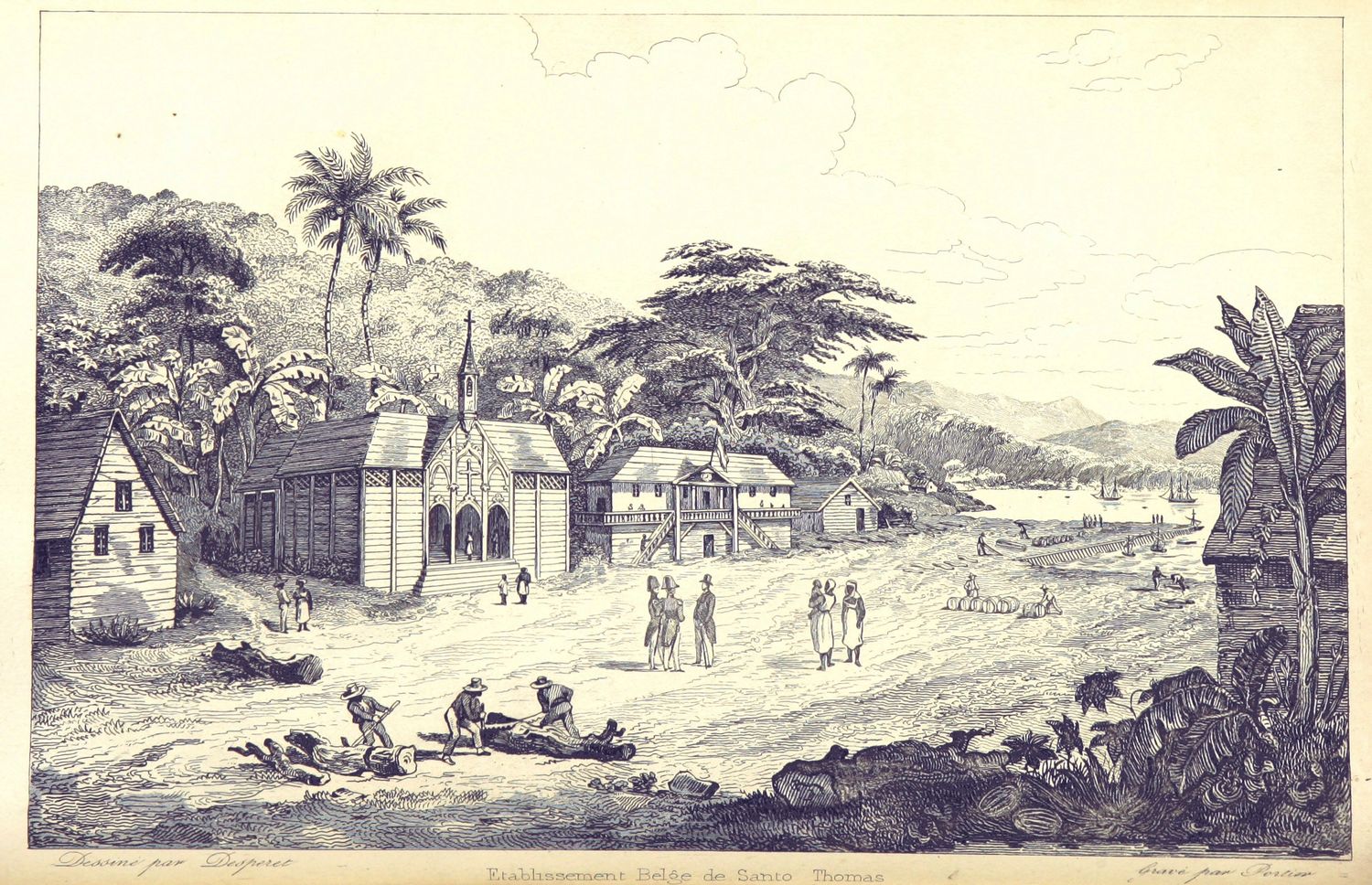

‘La misère des Flandres in trans-atlantisch perspectief’, in: Wereldgeschiedenis van Vlaanderen

Polis, 2018, 297-303.

Door arm Vlaanderen,

Van Halewyck, 2001 (heruitgave van het gelijknamige boek uit 1903).

Boer. Het noeste leven in West-Vlaanderen

Hannibal Books, 2017.

Vlaamse migranten in Wallonië 1850-2000

LannooCampus, 2011.

Van Franschmans en Walenmannen. Vlaamse seizoenarbeiders in den vreemde in de 19de en 20ste eeuw

Lannoo, 2008.

Boer vindt land. Vlaamse migranten en Noord-Amerika

Davidsfonds, 2014.

Vlamigrant. Over migratie van Vlamingen vroeger en nu

Davidsfonds, 2014.

Leven van het land. Boeren in België, 1750-2000

Davidsfonds, 2004.

Fiction

Wij, twee jongens

Davidsfonds Infodok, 2022. (16+)

Arm Vlaanderen

Vlaams Boekenfonds, 1984.