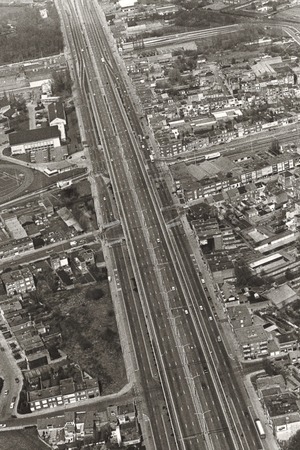

Aerial photograph of Heist-op-den-Berg. The ribbon development is visible on the panorama, 1958 | Kempenserfgoed.be, collectie Gaston Van den Broeck, photo GAH008000001

Ribbon Development

Spatial Planning in Flanders

Cobbled roads that wind from village centre to village centre, flanked on either side by villas, businesses, here and there a meadow and especially lots of improvised buildings: that view has been typical for decades of densely populated Flanders.

Almost a quarter of Flemish homes, but also many outlet stores are sited on connecting roads between municipalities. When added together those roads form a strand of 13,177 kilometres – more than the distance from Brussels to Singapore. Because of that ribbon development one built-up area merges almost unnoticed into the next.

Maps from the 18th century already show traces of ribbon development in the Austrian Netherlands. The flat landscape was well-suited to the building of homes and roads. But the real phenomenon dates mainly from after the Second World War. The government gave citizens and companies a great deal of freedom to build where they wanted. With the advent of the car the working Fleming was no longer forced to live close to a centre. Rural Flanders was divided up into one great residential zone.

Leuven, KADOC-KU Leuven. kfa015338

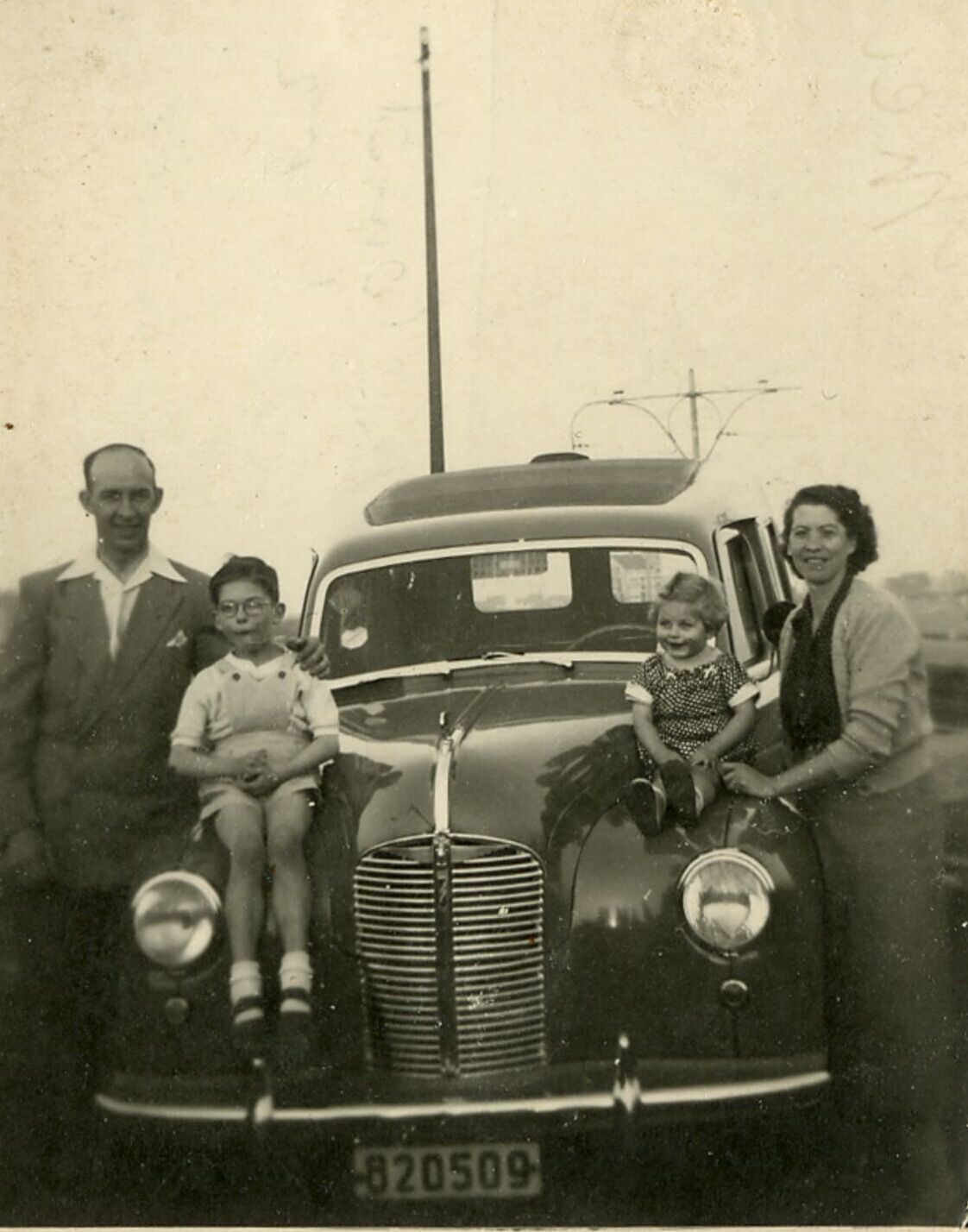

Minister of Health and the Family Alfred De Taeye (1905-1958) in Waregem (Province West-Flanders) at a laying of the first stone ceremony for the hundred thousandth economical home in 1954.

Spatial Planning in Flanders

The fragmentation of open space has early roots, but in the late 19th century it became a conscious aim. Administrators did not want too many workers to move into towns, for fear of social unrest. So they supported commuting and encouraged individual home ownership.

The housing shortage after the Second World War played even more into the hands of ribbon development and fragmentation of Flanders. At that time the government wanted to provide everyone with a good home. That was an important constituent of the welfare state. The Christian-Democratic party insisted on a house of its own for every family, preferably out of town. A law of 1948, named after its initiator, Alfred De Taeye, provided building subsidies and cheap loans.

The one-family homes mushroomed. There was as yet no spatial planning. Not until 1962 was the first law on spatial planning passed and later came regional plans which demarcated zones for housing, agriculture and industry. However, towns and municipalities seldom refused building permission and welcomed smaller plots. Moreover, from the 1990s onwards many shops moved to the connecting roads. The environment and mobility were the great victims of that evolution. The tailbacks particularly increased greatly. In 2022 they averaged on every working day 679 kilometres.

Focal points

Discover more on this topic

Non-fiction

Wonen in Welvaart. Woningbouw en wooncultuur in Vlaanderen, 1948-1973.

Vlaams Architectuurinstituut, 2006.

Het lelijkste land ter wereld

Davidsfonds 1968.

Het schoonste land ter wereld

Kritak, 1987.

Ugly Belgian Houses. Don’t try this at home

Borgerhoff & Lamberigts, 2015.

More Ugly Belgian Houses. Don’t try this at home

Borgerhoff & Lamberigts, 2021.

De golden Sixties: hoe het dagelijks leven in België veranderde tussen 1958-1973

Manteau, 2022.

Hoe zouden we graag wonen? Woonvertogen in Vlaanderen tijdens de jaren zestig en zeventig

Universitaire Pers Leuven, 2012.

Met voorbedachten rade. De sluipmoord op de open ruimte

Kritak, 2022.

Het Vlaamse platteland in de fifties

Davidsfonds Uitgeverij, 2012.

Wonen in Welvaart. Woningbouw en wooncultuur in Vlaanderen, 1948-1973

VAi, 2006.

Onder de kerktoren. Waarom Vlaamse dorpen toekomst hebben

Davidsfonds Uitgeverij, 2021.

Fiction

De voorstad groeit

Manteau, 1943.

Suske en Wiske, De Beestige Brug (nr. 343)

De Standaard, 2015.