Paul Panda Farnana graduates in 1907 from the State Institute for Horticulture in Vilvoorde. He is seen here with his fellow students (nine men and one woman) in the town park in Vilvoorde | Vilvoorde, Horteco

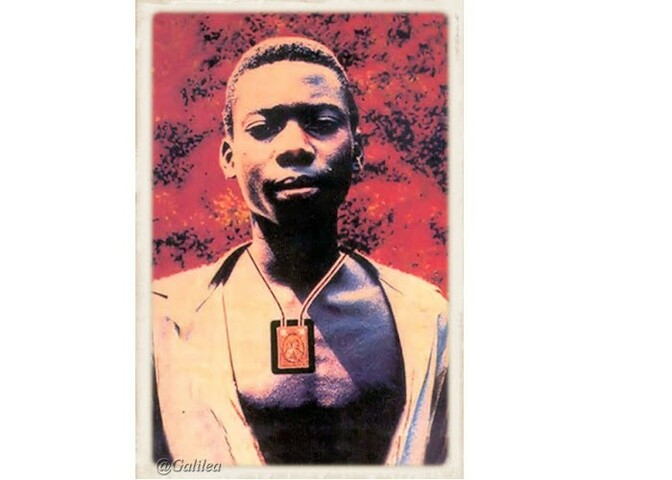

Paul Panda Farnana

Congo, Conquered and Colonised

Paul Panda Farnana was the first Congolese intellectual to openly criticise colonialism. Taken into her home by a Belgian woman at an early age, he was able to study in Belgium. He fought against Germany in the First World War and was a prisoner of war. After the war he became a human rights activist.

Farnana was the son of a Congolese chief. He found his way to Belgium as the servant of a trader and grew up in the latter’s sister’s house. In 1909, after studying at the Atheneum in Elsene, the State Institute for Horticulture in Vilvoorde, and pursuing advanced studies in Paris and Mons, he returned to Congo. There he worked as an agricultural engineer for the colonial authorities and saw how racism, exploitation and violence characterised colonialism.

After the First World War Farnana founded the Union Congolaise (1919) He took part in the Colonial Congress in the Belgian Senate (1920) and in the second Pan-African Congress in Brussels (1921). He pleaded on behalf of the Congolese for equal rights, higher wages and better access to education. In vain. In 1929 he returned to his home village of Nzemba, where he died a year later.

Wikimedia Commons

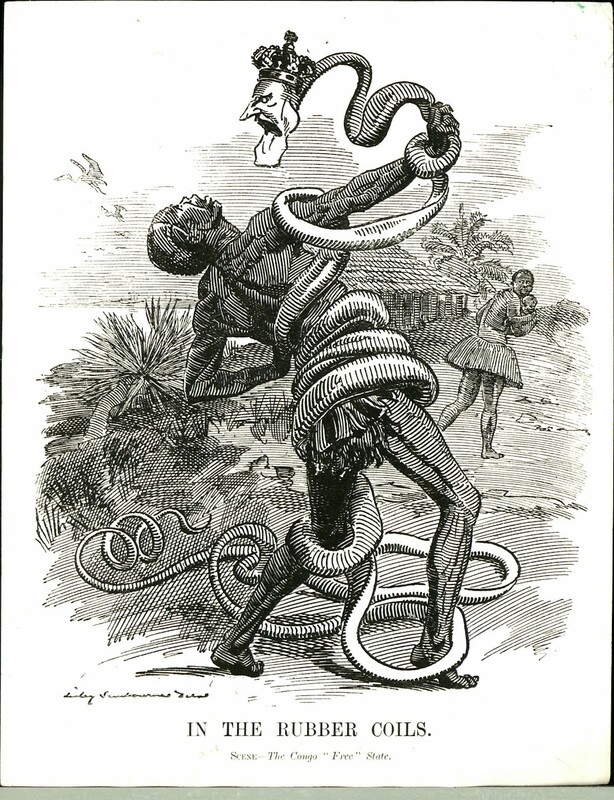

Leopold’s violent regime was sharply criticised in the British press. Cartoon by Edward Lumley Sambourne, published in 1906 in the satirical magazine Punch.

Congo, Conquered and Colonised

From the end of the 1870s on the Belgian King Leopold II, who had had colonial ambitions for quite some time, sent expeditions to Central Africa. Greedy for financial profit, he conquered an extensive area in the Congo basin. He created a private colony there with active support from the Belgian government, business world and church. In 1885 the great powers came to agreements on their sphere of influence in Africa and recognised Leopold II as sovereign of the Congo Free State.

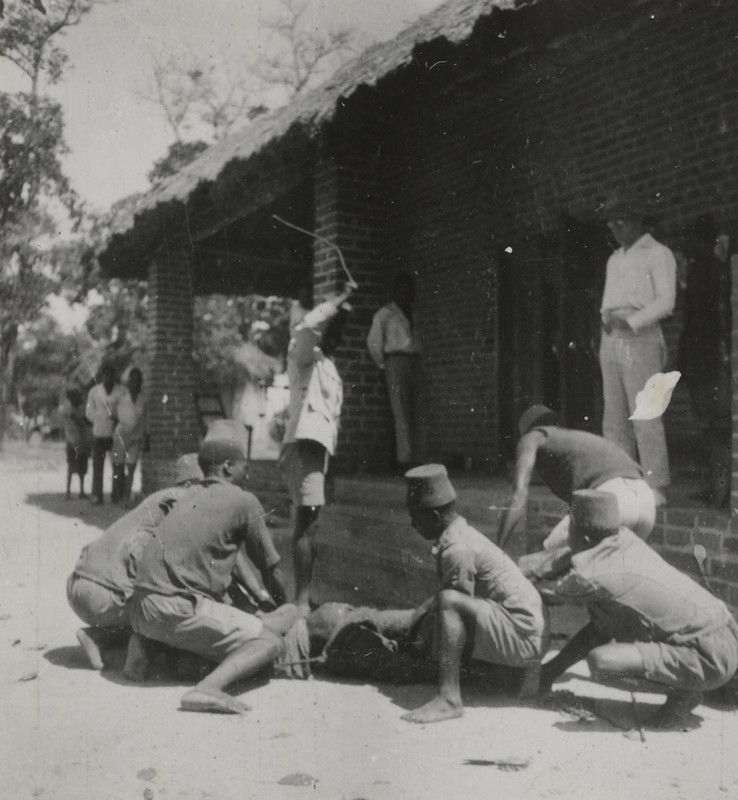

For Leopold II and his co-workers Congo was an investment that had to pay off. The rising demand for rubber from the 1890s on made Congo a rich source of income. In order to maximise this the Congolese were forced to harvest rubber. That went hand in hand with large-scale atrocities, which were subject to much international criticism. The violent regime of Leopold II, together with an epidemic of sleeping sickness, led to a marked drop in population. In 1908 the Belgian state took over power and Congo became a Belgian colony.

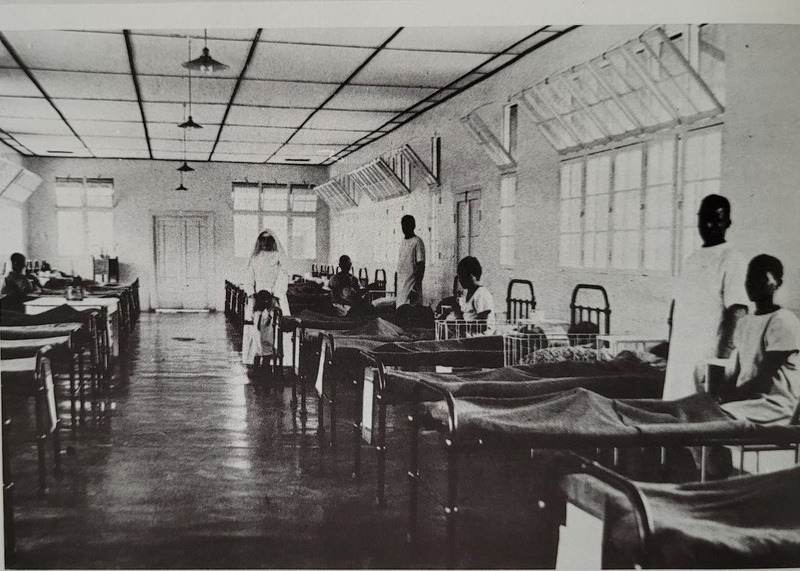

In the Belgian Congo there were at most a few tens of thousands of Belgian officials, managing directors and missionaries active. In order to govern, exploit and convert the colony they appealed to large groups of Congolese subordinates: clerks, nursing assistants, catechists, soldiers… Congolese who like Paul Panda Farnana were given a senior post, were an exception.

After the Belgian takeover of 1908 colonisation continued to mean in the first instance for the Congolese occupation and subjection: forced taxes and forced labour in the copper mines, in road building or in the plantations. Repression made them toe the line. The profits went to a small group of Belgian entrepreneurs. Antwerp and Brussels were drivers of the colonial trade.

Focal points

Discover more on this topic

Non-fiction

Congo 1885-1960. Een financieel-economische geschiedenis

Epo, 2007.

De moord op Lumumba

Van Halewyck, 1999

De teloorgang van een modelkolonie. Belgisch Congo 1958-1960

Acco, 2008

Congo 1876-1914. Veroverd, bezet, gekoloniseerd

Sterck & De Vreese, 2020.

Death in the Congo. Murdering Patrice Lumumba

Harvard, 2015

Koloniaal Congo. Een geschiedenis in vragen

Polis, 2020.

De geest van koning Leopold II en de plundering van de Congo

Meulenhoff, 2020.

Een verzwegen leven: onze Congolese geschiedenis in België

Uitgeverij Vrijdag, 2023.

Knack Historia, Congo. Meer dan een kolonie

2018.

Dochter van de dekolonisatie

Epo, 2020.

Congo. Een geschiedenis

De Bezige Bij, 2021.

Congo. De impact van de kolonie op België

Lannoo, 2007.

Fiction

Paul Panda Farnana, een vergeten leven

Africalia, 2014. (stripalbum)

Congo 50

Africalia, 2010. (stripalbum)

Africa Dreams

Casterman, 2021. (reeks van stripalbums)

Hart der duisternis

L.J.Veen Klassiek, 2021.

Yaka mama

Davidsfonds, 2002. (12+)

Ik ben de jachtluipaard: een roman over Belgisch Congo

Clavis, 2021. (12+)

Kongokorset

Vrijdag, 2019.

De mensengenezer: roman

De Bezige Bij, 2018.

Kongo, de duistere reis van Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski

Scratch, 2014.

Congo blues: roman

Cossee, 2017.

Tropenwee

Standaard Uitgeverij, 2023.

Vuurvader

Standaard Uitgeverij, 2022.

Zoon in Congo: zoektocht naar een vader

Lannoo, 2015.

Het land dat nooit was: een tegenfeitelijke geschiedenis van België

De Bezige Bij, 2015.

Oproer in Kongo

Manteau, 1990.