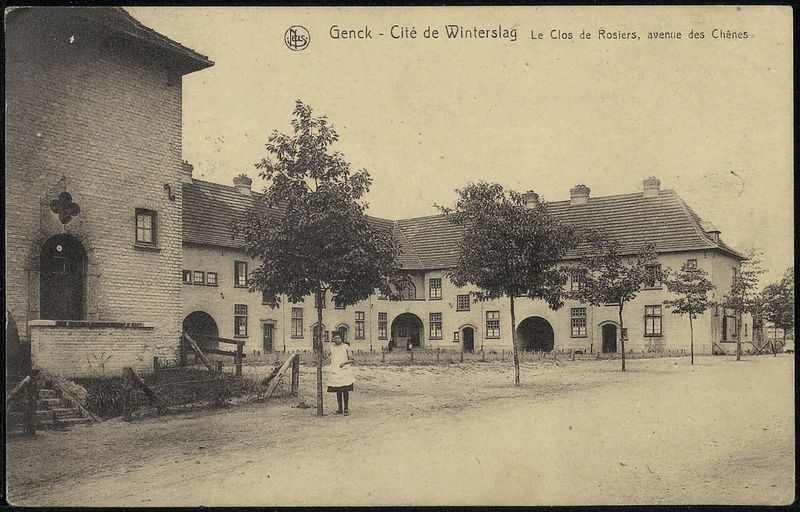

Winterslag, the first mining village in Limburg, 1923. Today it houses Feniks, previously the Limburg Associazioni Cristiane Lavoratori Italiani (ACLI) | Genk, Collectie Geheugen van Genk, Emile Van Dorenmuseum

Multicultural Mining Villages

Coal in Limburg

The discovery of coal in Central Limburg in 1901 heralded a new era for the region. There suddenly appeared in the quiet Limburg Campine derricks, roads, railway lines and new estates. The mining villages were gradually populated by workers from home and abroad.

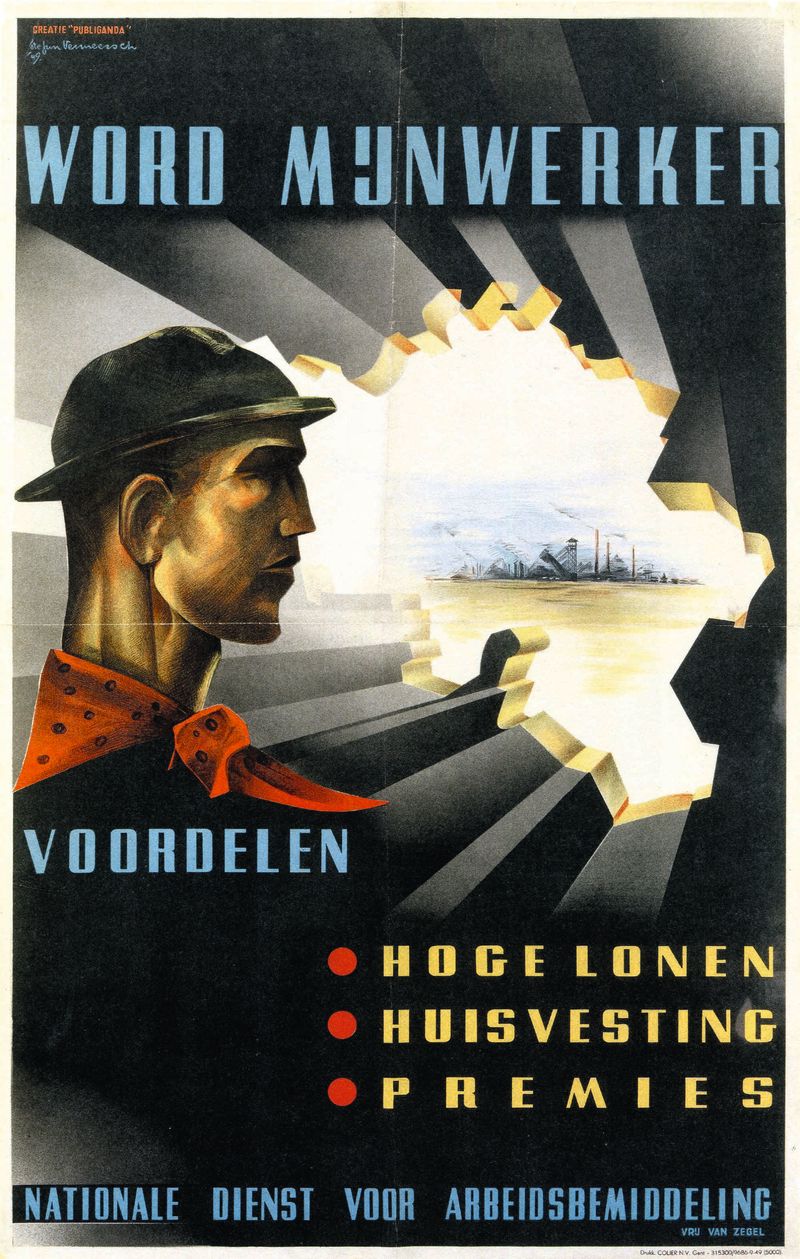

To mine the recently discovered coal seams, various mining companies established themselves in Limburg. There was no shortage of capital for the developers, though there was one of labour. Because the region was sparsely populated, the future workforce must come from elsewhere. For those thousands of workers and their wives the mining companies had mining villages or cités built. Besides houses they built schools and churches, sports infrastructure and theatre auditoria. In this way the mine bosses exercised a lot of control over their employees.

The plan of the mining boards to attract workers from far and wide with green streets and nice houses, was only a partial success. So they recruited miners from Eastern and Southern Europe, Turkey and North Africa. Hence the mining villages grew into a melting pot of languages, cultures and religions.

Hasselt, State Archives

After the discovery of coal deep underground, drilling towers appeared on the Limburg heathlands. The photo shows the construction of the Winterslag mine, 18 April 1910.

Coal in Limburg

The discovery of coal in Limburg in the summer of 1901 was great news. At the time coal was the principal source of energy and so many hoped that the poor province would progress towards a period of prosperity and economic development.

Large financial and industrial groups, which were also active in Wallonia, set up mining companies in Limburg in 1907. They faced great challenges: the coal seams were at a depth of five hundred metres or more that was difficult to reach. In addition, the sparsely-populated heathland lacked many basic provisions, such as sufficient housing and road infrastructure. In 1914 the war also broke out. As a result, the first mine – Winterslag in Genk – did not go into production until 1917. In the next few years five other mines opened. At the height of their exploitation, shortly after the Second World War, they provided employment for a labour force of 44,000 workers.

The coal mines brought the Catholic, rural population into contact with phenomena from the modern industrial world, such as Socialism and trades unions. In addition, the coal industry brought a strong increase in population with a very diverse cultural composition. Seldom had one branch of industry in Flanders transformed a whole region so fundamentally in such a short time.

Focal points

Discover more on this topic

Non-fiction

Iedereen zwart: het samenleven van nieuwkomers en gevestigden in de mijncité Zwartberg, 1930 – 1990

Aksant, 2007.

De Belgische Kolenslag 1944-1951: het mirakel dat er geen was

Algemeen Rijksarchief, 2021.

In de put. De arbeidsmarkt voor mijnwerkers in Belgisch-Limburg, 1900-1966

Verloren, 2016.

Limburg in 9 vragen

OKV, 2018.

Een eeuw steenkool in Limburg

Lannoo, 1992.

Mijnerfgoed in Limburg. Ondergronds verleden, bovengrondse toekomst

OKV, 2012.

De ereburgers: een sociale geschiedenis van de Limburgse mijnwerkers

EPO, 2000.

Diep. De mijnologen

Coalface, 2018.

Fiction

De put: een stomme film

SUN, 1988.

Licht in de tunnel: Emiel, ridder van de mijn

Clavis, 2022. (9+)

Voor Paulien

Averbode, 1995.(12+)

Koolputtersvolk

Pro Arte, 1946.

Nu kijken

Bijkomend kijk/luister materiaal

De mijnen. 14 films over de Belgische steenkoolmijnen

(dvd)

50 jaar Turkse migratie

(dvd)

Marcinelle

(2003).

Marina

(2014).