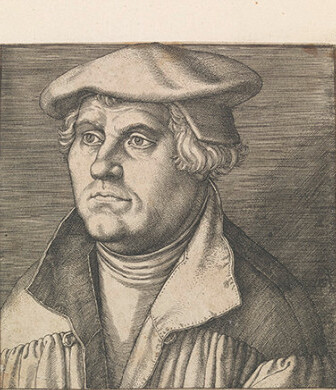

Erasmus

Humanism

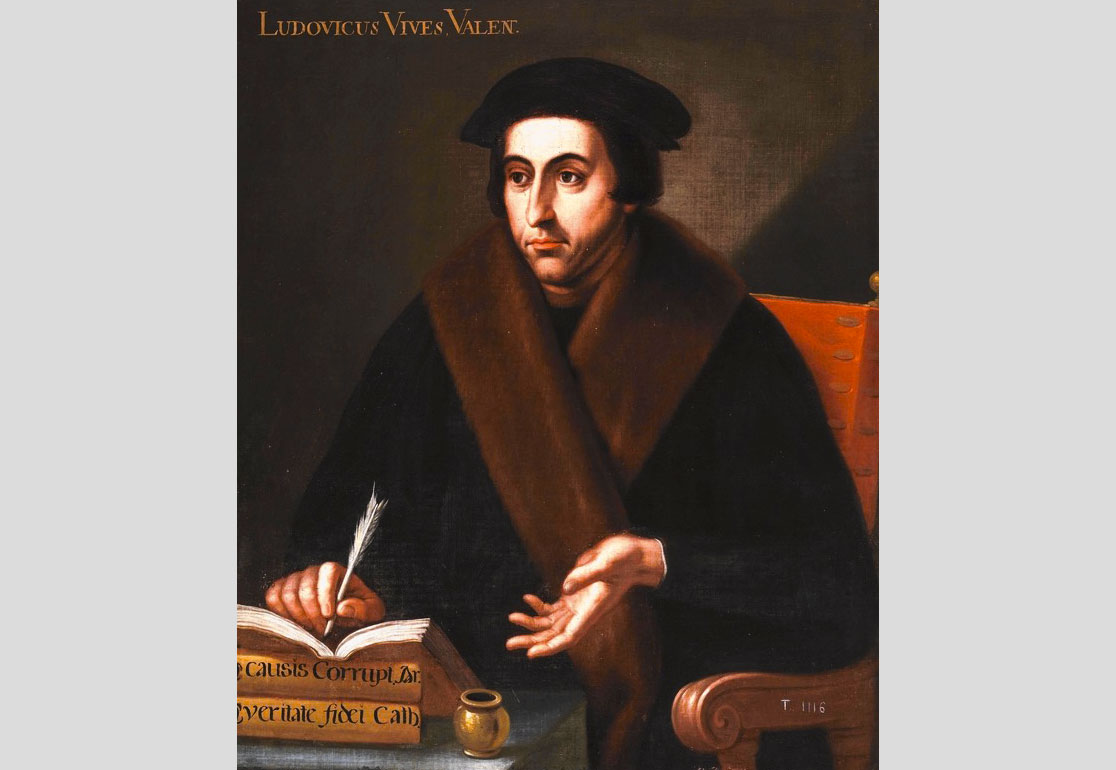

Erasmus was one of the most influential European thinkers of the 16th century. He wrote on the upbringing of children and education and sharply criticised the church and those in power. His writings helped to shape the philosophical and religious thinking of his time.

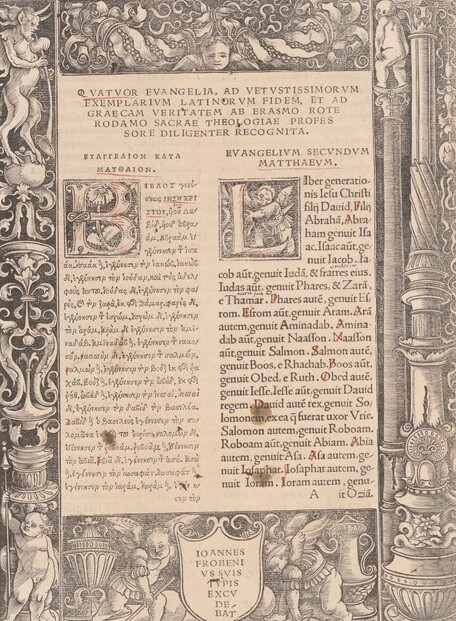

Erasmus was born in Rotterdam – that Holland town belonged at the time to the Burgundian Netherlands – but travelled through Europe all his life. Thanks to his exceptional knowledge of Greek and Latin literature he was able to bring antiquity back to life. His most ambitious achievement was the edition of the New Testament published in 1516. That section of the Bible had originally been written in Greek, but for a thousand years the church had used a not always reliable Latin translation. Erasmus published the Greek source text and produced a new Latin translation with a commentary. That translation undermined traditional interpretations of the Bible. In Leuven Erasmus was the driving force behind the Collegium Trilingue or Three-Language College. There students could study the three Biblical languages – Hebrew, Greek and Latin – together.

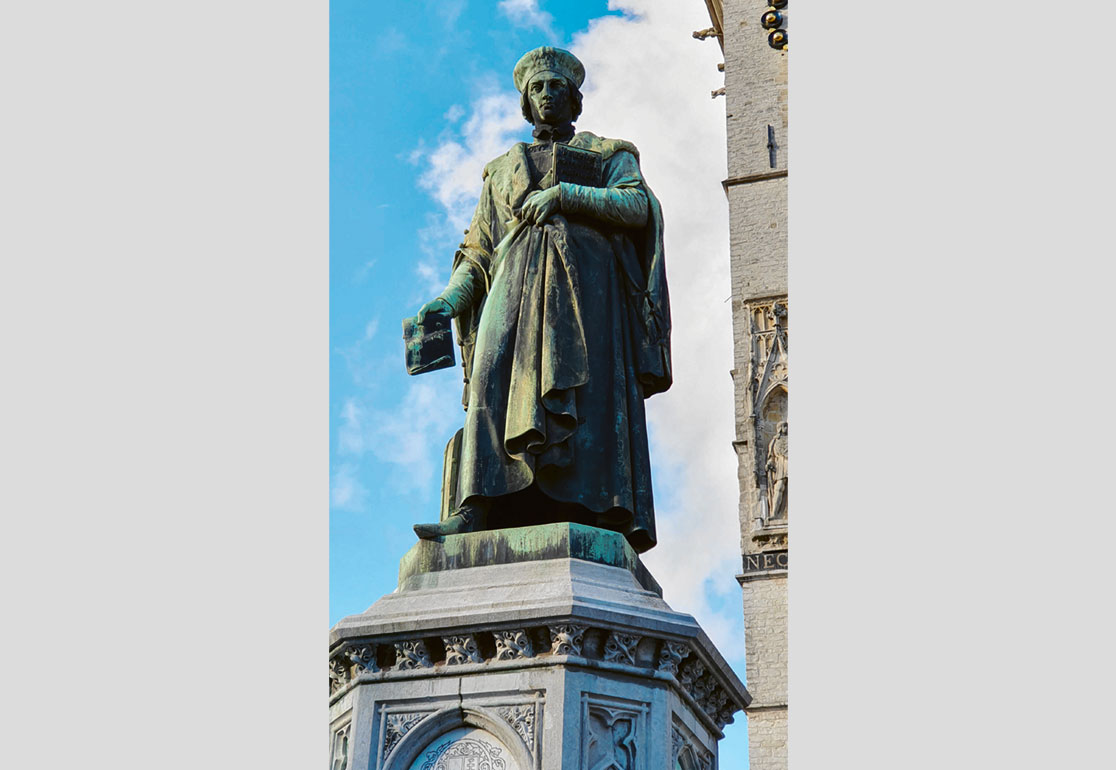

University Library KU Leuven, visualisation Timothy de Paepe

Reconstruction of the Three-Language College in Leuven. The institution was a breeding ground for humanists like Gemma Frisius, Andreas Vesalius, Gerard Mercator and Rembert Dodoens.

Humanism

Erasmus was a figurehead of humanism. That is an intellectual movement which in the 15th and 16th century spread across Europe from Italy. The humanists encouraged critical thinking. They argued for a philosophy and ethics that put man at the centre of things (hence: humanism). That opened the door for innovation in many subject areas, such as language study, mathematics, anatomy, cartography, botany, medicine…

The humanists found their inspiration in the Classical Latin and Greek texts, which they studied, admired and imitated. They purged the ancient texts of mistakes and deliberate changes that had gradually crept in. In this way they laid the foundations of philology, the scholarly study of language and literature.

The humanists also studied the history and philosophy of antiquity. They felt that people from the upper classes needed that knowledge to play their leading role in society. Reform of education was therefore important. For example, at school one should master Latin by using the language actively and not learn grammatical rules off by heart without understanding them.

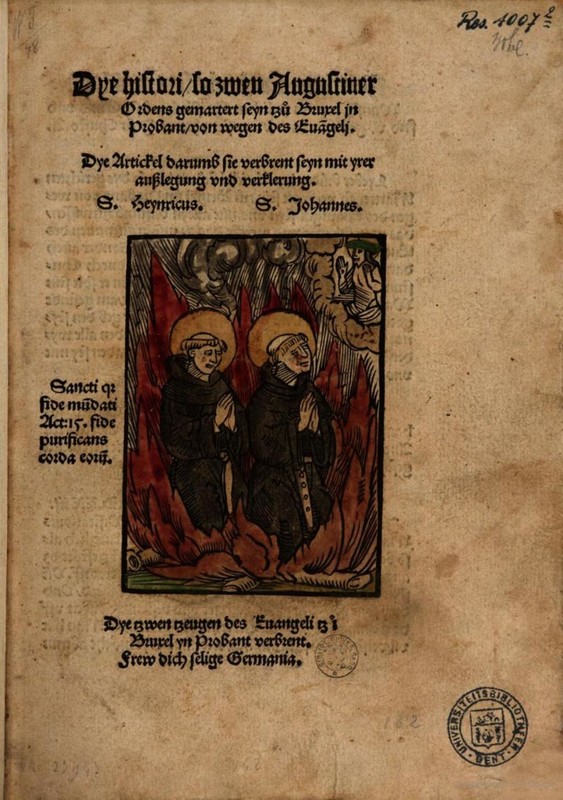

North of the Alps humanists like Erasmus also studied the Bible and the church fathersChristian writers and teachers from the 2nd to the 7th centuries who have authority within the Catholic church as proclaimers of the truth. . It was intended to lead to a purer Christianity, closer to the Gospel, stripped of abuse, hollow rituals and contrived theological arguments.

Focal points

Discover more on this topic

Non-fiction

Erasmus

Athenaeum – Polak & Van Gennep, 2020.

Geloof alleen! Protestanten in België: een verhaal van 500 jaar

Garant, 2017.

De eerste protestanten in de Lage Landen: geloof en heldenmoed

Davidsfonds, 2004.

Vrouwengesprekken: een keuze uit de Colloquia

Athenaeum – Polak & Van Gennep, 2005.

Balthasar Moretus en de passie van het uitgeven

BAI, 2018.

Gelukkige stad. De gouden jaren van Antwerpen (1485-1585)

Amsterdam University Press, 2017.

De woordenaar. Christoffel Plantijn, ‘s werelds grootste drukker en uitgever 1520-1589

Balans, 2014.

Erasmus: dwarsdenker; een biografie

De Bezige Bij, 2021.

Belgisch protestantisme in perspectief: doorkijkjes in 450 jaar ideeëngeschiedenis

Houtekiet, 2011.

Antwerpen in de tijd van de Reformatie: ondergrond protestantisme in een handelsmetropool 1550-1577

Meulenhoff, 1996.

Het gevleugelde woord. Geschiedenis van de Nederlandse literatuur 1400-1560

Bert Bakker, 2007.

Anna Bijns, van Antwerpen

Bert Bakker, 2011.

Protestantisme: aspecten van de reformatie tussen humanisme en verlichting

Academia Press, 2014.

Antwerpen. De gloriejaren

De Bezige Bij, 2021.

Op reis met Plantijn. Onderweg in de 16de eeuw

BAI, 2021.

Fiction

Erasmus in Europa

Erasmus Universiteit, 2009. (9+)

De droom van Christoffel

Uitgeverij Vrijdag, 2016. (OKAN, 14+)

Het geheim van Erasmus

Mozaïek, 2006. (13+)

Het manuscript van Giudecca

Atlas, 2005.

De schaduw van Erasmus: historische roman

Houtekiet, 2006.

De verloren droom van Pieter Gillis: historische roman over Antwerpen tussen Reformatie en humanisme

Davidsfonds, 2010.

Wentelsteen: Erasmus en de moeizame geboorte van het Collegium Trilingue: historische roman

Davidsfonds Uitgeverij, 2017.

Het geheim van Plantyn

De Vries-Brouwers, 2010.

Suske en Wiske: De Geplaagde Plantijn (nr. 366)

Standaard, 2023.

Storm: de verboden brief van Maarten Luther

Ark Media, 2019. (9+)

Tikkie terug!; de tijdreis van Bas

Museum Gouda, 2016. (9+)

Zotten zijn wij die gedichten schrijven: Goudse dichters over Erasmus

De Vrije Uitgevers, 2019.

Life is beautiful

30 kortfilms over dromen, leven en liefde, met als uitgangspunt spreuken van Erasmus (A Film, 2011).

Storm: letters van vuur

(2017)

TRAPMAN, Hans, Erasmus: een hoorcollege over zijn leven, oeuvre en de invloed van zijn denken

Home Academy, 2013.

Hollands grootste humanist

De Vrije Uitgevers, 2012.