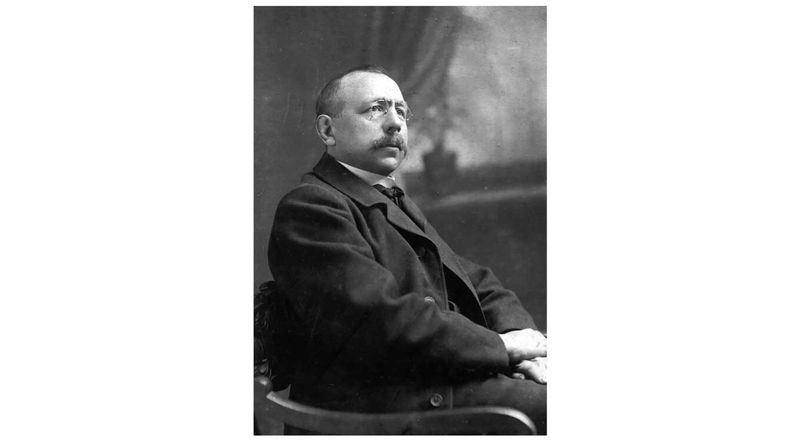

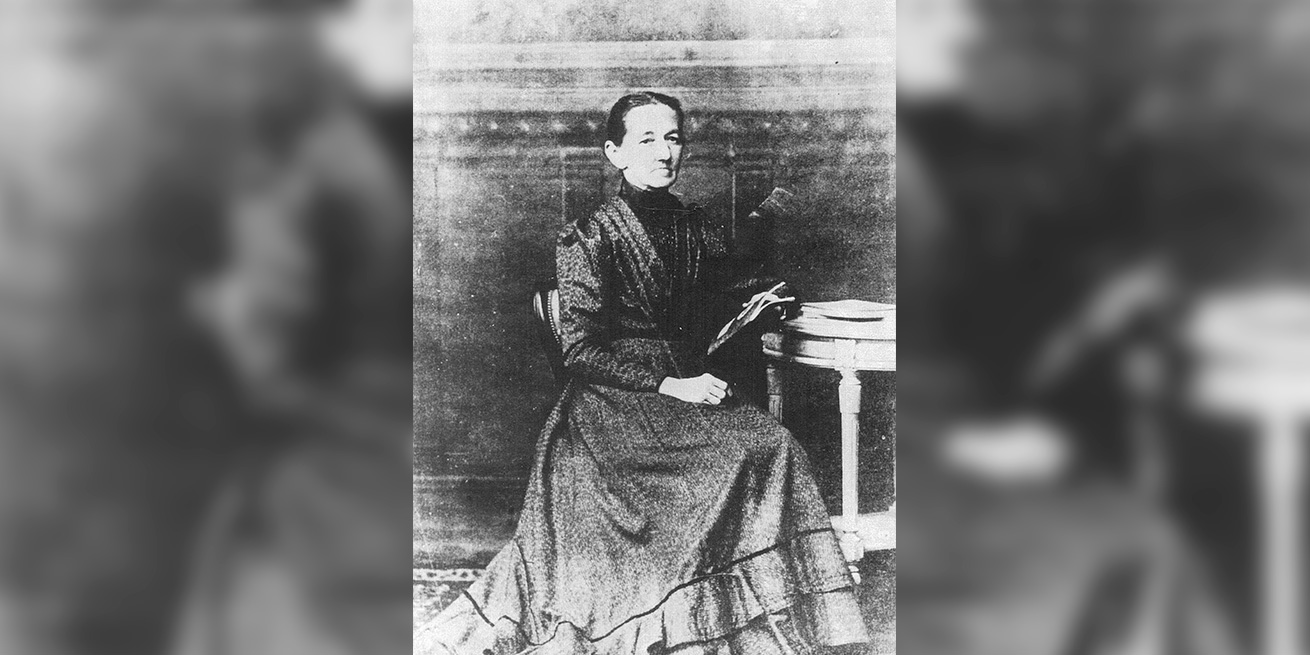

Portrait of Emilie Claeys. The only known photo, about 1900-1920 | Ghent, Amsab-ISG, fo004473

Emilie Claeys

The ‘Social Question’ in the 19th Century

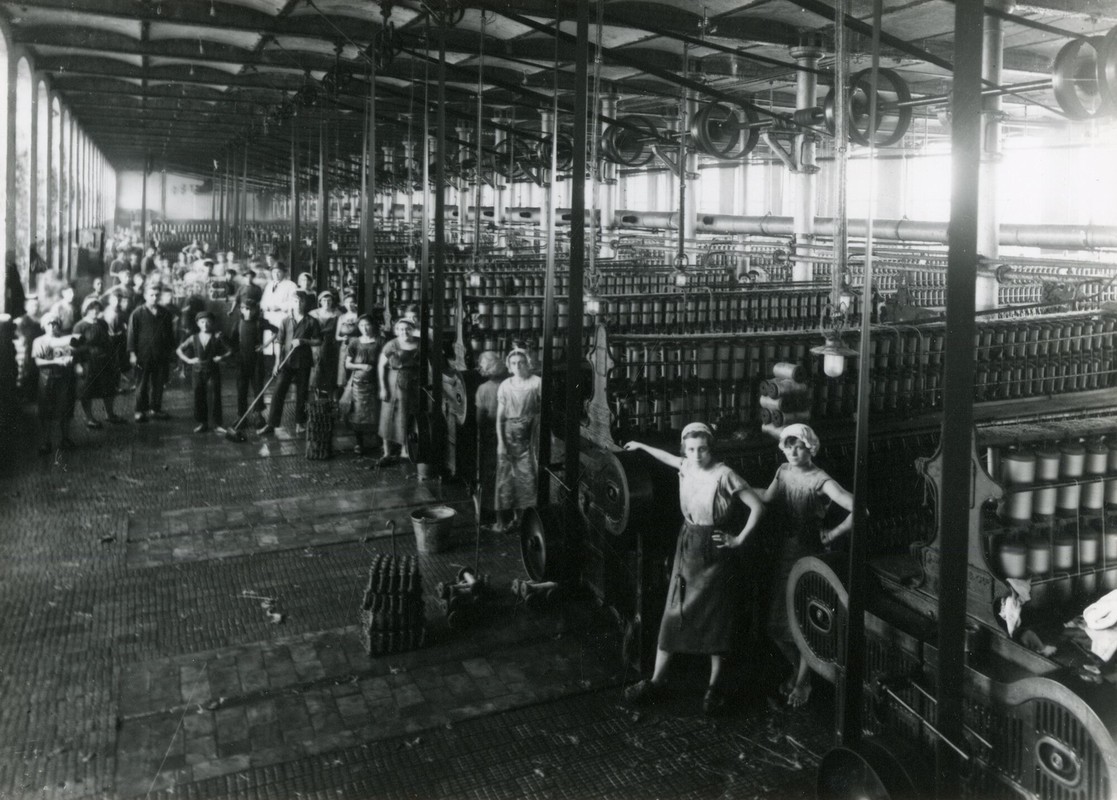

In the nineteenth century working conditions in the Ghent spinning mills were particularly bad. Women workers had to make do with a wage that was even lower than the man’s starvation wages and they were often victims of sexual abuse. In addition, after a tiring day’s work in the factory, lots more work awaited them at home. For that reason the Ghent textile worker Emilie Claeys committed herself to the emancipation of workers and women.

In 1886 the 31-year-old Claeys founded the Socialist Propaganda Club for Women. She also joined the recently founded Belgian Workers’ Party (BWP). From 1891 she formed part of the party’s committee. She argued for equal pay and better working conditions. Thanks to her women’s suffrage for a short time formed part of the Socialist electoral programme. However, within the Socialist movement the traditional image of women remained dominant. Some of the issues raised by Claes, such as the reassignment of household chores and her support of birth control met with little enthusiasm. In 1895 a disillusioned Claeys took her leave of the movement.

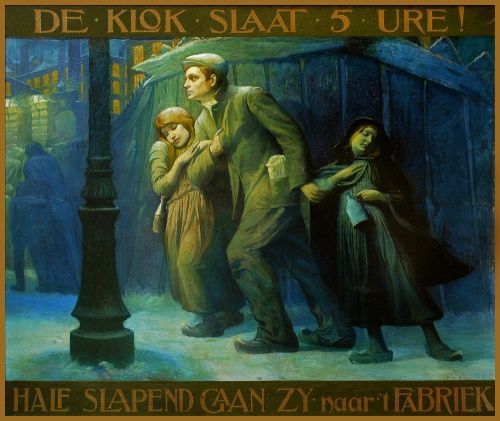

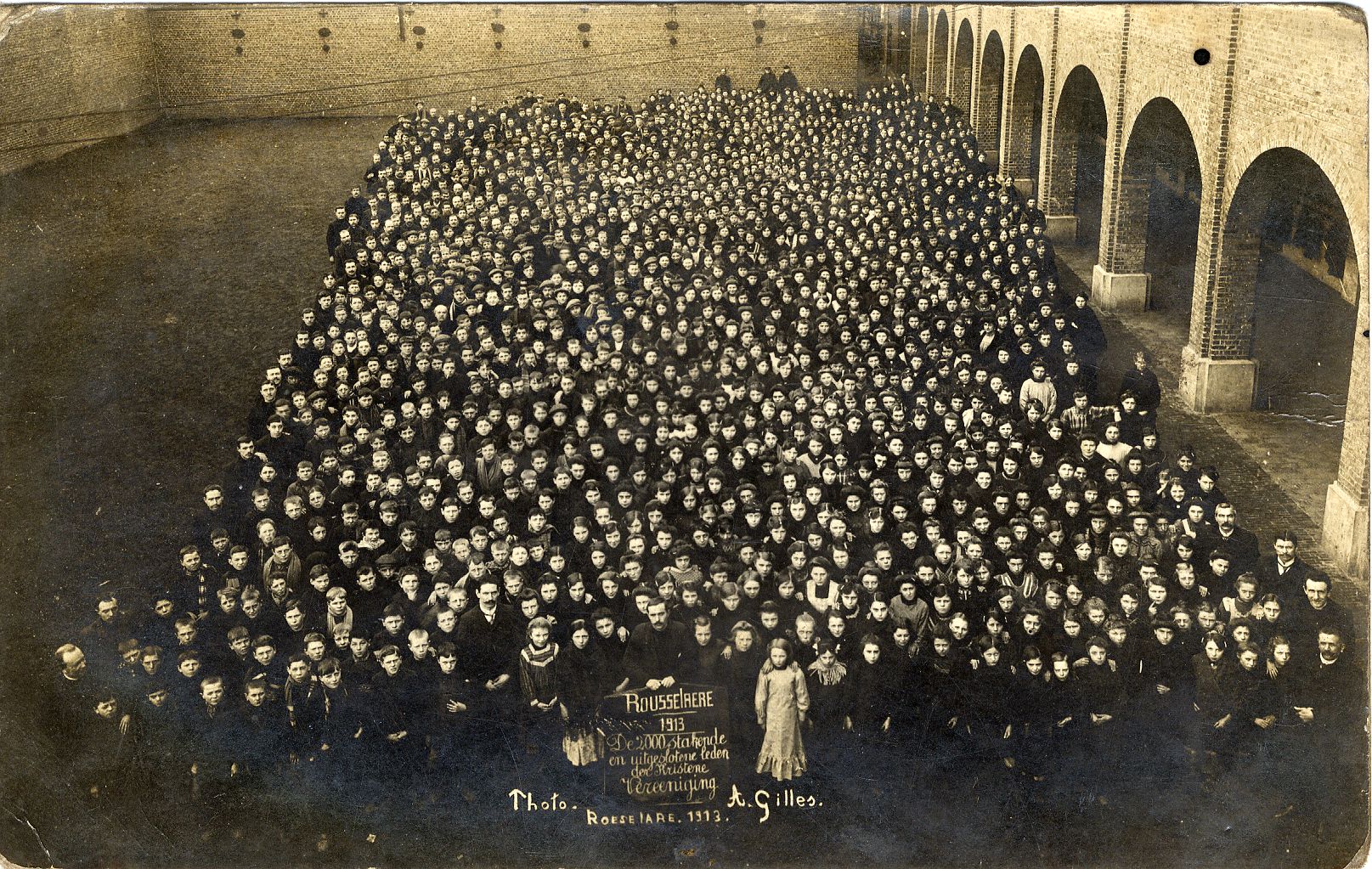

Brussels, KIK-IRPA, cliché A025603, Edmond Sacré

Living conditions in Ghent, end of the 19th century.

The ’Social Question’ in the 19th Century

In the second half of the 19th century Belgium became an industrial country. More and more people worked as wage slaves in the fast-growing factory industry. A small group of entrepreneurs made huge profits, while a mass of workers – men, women and children – lived in pitiable circumstances. Working days of fourteen hours were no exception, wages were impossibly low, the work was dangerous and living conditions were unhealthy. There was no social safety net, in the case of illness, industrial accident, unemployment or old age. Workers were dependent on the charity of their employers. When in the 1870s a worldwide recession broke out the social situation worsened. Wages fell and unemployment rose. The situation in the textile industry in towns like Ghent, Aalst, Ronse and Roeselare was harrowing.

Contemporaries were not blind to the deep misery. Particularly the factory work of women and children upset social involved citizens – progressive Liberals, freemasonsfreemasonry is a movment that originated in the 18th century and strives for cooperation, progress and making sense of the world, separate from religious convictions. and Catholics with a social conscience. Yet not even bills forbidding child labour were approved by parliament before the end of the century. Workers had no vote and employers hid behind the so-called ‘economic freedom’ to resist government intervention on wages and working conditions. As a result, Belgium was behind other industrial nations like England and France in the field of social protection.

Focal points

Discover more on this topic

Non-fiction

Vader Anseele: Edward Anseele (1856-1938), politicus, ondernemer, mythe

Vrijdag, 2019.

Tussen twee stoelen: Emilie Claeys (1855-1943), feministe en socialiste

Historica, 1997, 2, p. 3-5.

Wat zoudt gij zonder ‘t werkvolk zijn?: de geschiedenis van de Belgische arbeidersbeweging 1830-2015

Van Halewyck, 2015.

En de vrouwen? Vrouw, vrouwenbeweging en feminisme in België (1830-1960)

Masereelfonds, 1980.

Sire, het volk mort. Sociaal protest in België 1831-1918

Hadewijch, 1997.

België. Een geschiedenis van onderuit

Epo, 2012.

De christelijke arbeidersbeweging in België

2 dln., UPL, 1991.

Wat zoudt gij zonder ’t vrouwvolk zijn? Een geschiedenis van het feminisme in België

Uitgeverij Vrijdag, 2018.

Vergeten vrouwen. Een tegendraadse kroniek van België

Emilie Claeys (1855-1943). Feministische heilige, socialistische dissidente of speelbal van de wisselvalligheden van het lot. Een kleine oefening in historische kritiek

Brood en Rozen, 1996, 3, p. 67-81.

Daens

Sterck en De Vreese, 2020.

Fiction

De Kapellekensbaan

Athenaeum – Polak & Van Gennep, 2018.

Pieter Daens, of hoe in de negentiende eeuw de arbeiders van Aalst vochten tegen armoede en onrecht

De Arbeiderspers, 2014.

Mathilde, ik kom je halen

Clavis, 2018. (9+)

Strijdlawijt, Honderd jaar werkmansliederen

EPO, 2013.

Daens

Stijn Coninx (Universal, 2000).