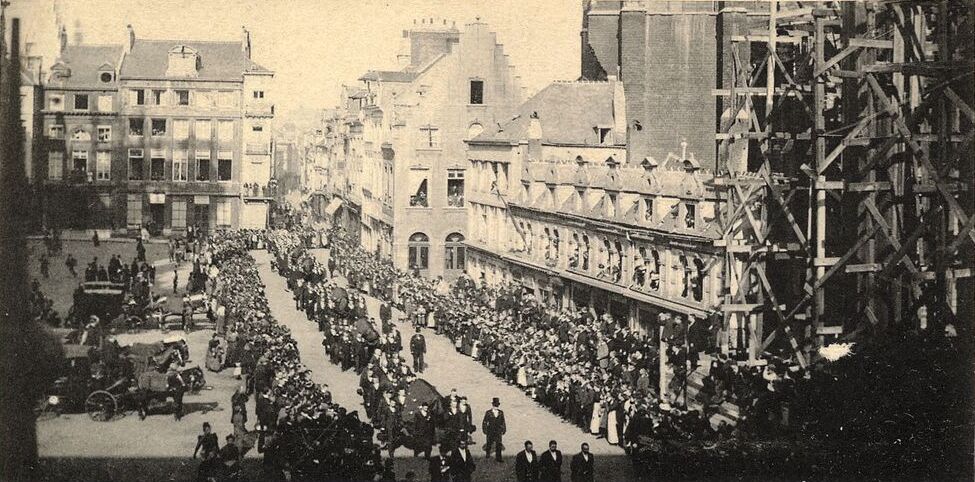

Mourning procession for five victims of the demonstration for universal (male) suffrage in the market-place in Leuven, 1902 | Ghent, Amsab-ISG, pk000044

Bloodbath in Leuven

Fighting for the Vote

In the evening of 18 April 1902 demonstrating workers marched through Leuven. They were protesting because parliament had just rejected the one man-one vote system. At nine o’clock in the evening the Civil Guardan official volunteer organisation for keeping public order, not a private militia. opened fire on the demonstrators. With fatal results: five demonstrators died on the spot, a sixth died the following day, fourteen were wounded. The event went down in history as the Bloodbath of Leuven.

The demonstration was an initiative of the Belgian Workers’ Party and was part of a wider campaign for universal suffrage. Every man must be given one vote in the parliamentary elections, the Socialists believed. With demonstrations like this and even a general strike they wanted to assert their rights by force.

However, the Catholic government would not give in. The campaign ended in defeat, demonstrations like that in Leuven turned into a bloodbath. And the Leuven dead were not to be the last. The struggle to let everyone participate fully in politics was far from over.

Ghent, Amsab-ISG, fo009534

Workers in Lokeren strike for single-vote universal (male) suffrage in 1912.

Fighting for the Vote

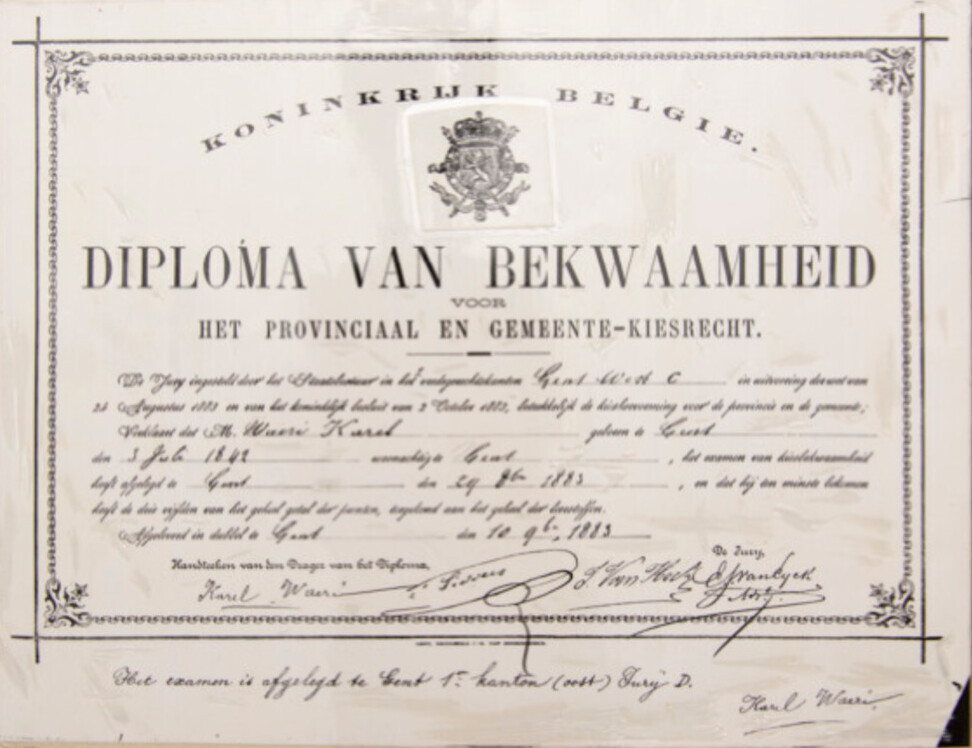

Until the end of the 19th century few Belgians had a say in politics. The census suffrage applied: only male Belgians who paid enough taxes, were allowed to vote. The drafters of the constitution regarded wealth as guarantee of political responsibility. In so doing they were confirming the existing power relations. In 1892 scarcely 2% of all Belgians decided who was elected to parliament.

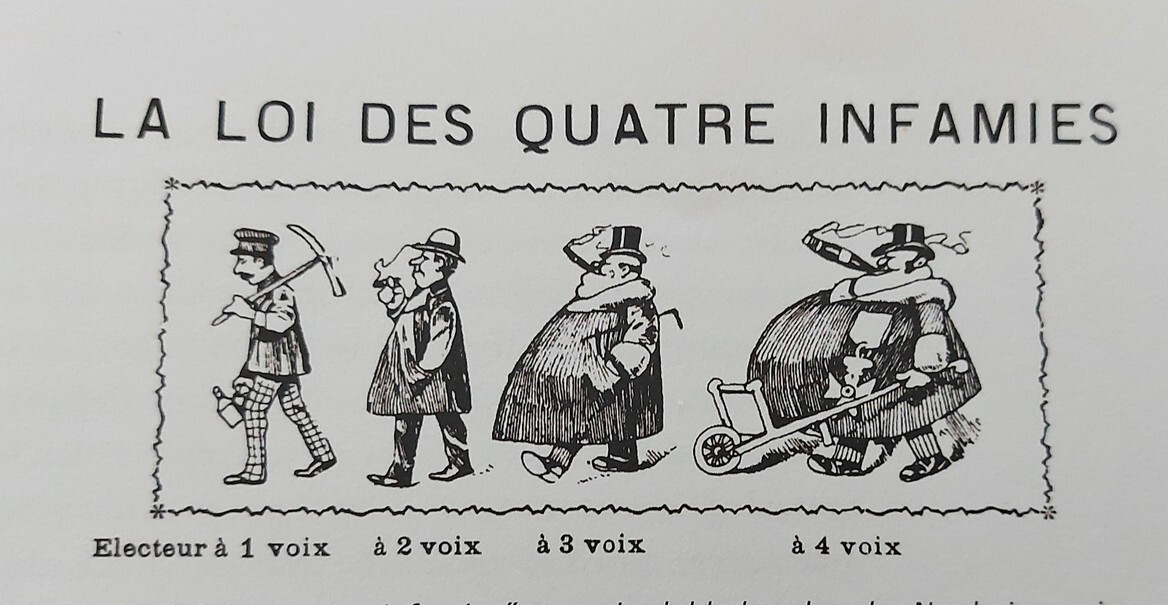

The young Socialist movement wanted a change and demanded universal suffrage. Catholics and Liberals were afraid that the workers would vote en masse for the ‘radical’ Socialists and kept their foot firmly on the brake. In 1893, under pressure from protests and strikes parliament approved a compromise: universal male suffrage with plural voting rights, coupled with compulsory voting. All men over 25 must now vote, but anyone who was married, paid taxes or had studied, was given two or even three votes. In that way the elite remained dominant.

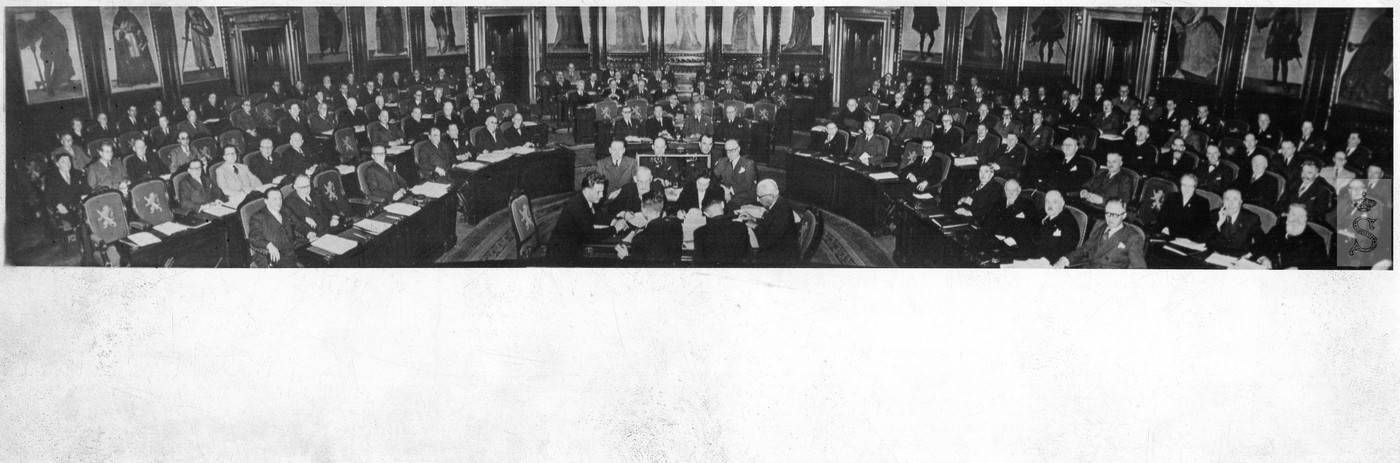

Socialists, from 1899 supported by the Liberals, continued to campaign for a fairer system: the one man-one vote system. That reform came only after the First World War, when revolution was brewing everywhere in Europe. After four years’ mobilisation of workers at the front political equality was bound to follow. In 1919 all men over 25 were given one vote. Women were excluded, apart from a small group.

Focal points

Discover more on this topic

Non-fiction

De bloednacht van 18 april 1902, Leuven op de bres voor het algemeen stemrecht

Salsa!, 2019.

1900. België op het breukvlak van twee eeuwen

Lannoo, 2006.

Léonie. Burgemeester tussen dorp en adel

Davidsfonds, 2021.

Een vrouw, een Stem: een tentoonstelling over vrouw en stemrecht in België 1789-1948

Brussel, 1996.

Geschiedenis van de Belgische Kamer van Volksvertegenwoordigers 1830-2002

Kamer van Volksvertegenwoordigers, 2003

November 1918. De terugkeer van de koning

In: Lerneux Pierre en Peeters Natasja (red.), De Groote Oorlog voorbij. België 1918-1928, Tielt, 2018, p. 30-37.

De schaduw van het interbellum. België van euforie tot crisis, 1918-1939

Lannoo, 2017.

Tien vrouwen in de politiek: de gemeenteraadsverkiezingen van 1921

Brussel, 1994.

Leve het algemeen stemrecht! Vive la garde civique! de strijd voor algemeen stemrecht, Leuven 1902

Peeters, 2002.

Nieuwkomers in de politiek. Het parlementaire debat omtrent kiesrecht voor vreemdelingen in Nederland en België (1970-1997)

Academia Press, 1998.

De geschiedenis geweld aangedaan. De strijd voor het vrouwenstemrecht 1886-1948

DNB, 1981.

Vrouw en politiek in België

Lannoo, 1998.

Fiction

Het land dat nooit was: een tegenfeitelijke geschiedenis van België

De Bezige Bij, 2015.